Cost of goods sold (COGS) may be one of the most important accounting terms for business leaders to know. COGS includes all of the direct costs involved in manufacturing products. Understanding COGS, and managing its components, can mean the difference between running a business profitably and spinning on the proverbial hamster wheel to nowhere.

What Is Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)?

COGS is an accounting metric that represents the direct costs of producing goods. It includes the cost of materials, labor, and allocated overhead directly connected to purchasing or creating the products that companies sell to generate revenue.

COGS, also referred to as “cost of sales,” appears on the income statement directly beneath revenue. Under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), companies must follow specific rules on which costs to include in COGS and how to calculate them. This standardized approach positions COGS as a critical component in determining two key business metrics: gross profit (revenue minus COGS) and gross margin (gross profit divided by revenue). The higher a company’s COGS, the lower its gross profit and margin, directly impacting profitability and competitiveness.

Key Takeaways

- Understanding and managing COGS helps leaders run their companies more efficiently and more profitably.

- COGS includes all direct costs needed to produce a product for sale.

- Different inventory-valuation methods can significantly impact COGS and gross profit.

- Tax rules allow an expanded version of COGS, which can reduce tax liability.

Video: What Is COGS?

Cost of Goods Sold Explained

COGS serves as a fundamental indicator of the health and efficiency of a business’ core operations. By tracking direct production costs, companies can identify changes in their manufacturing or acquisition processes over time and make adjustments before costs balloon and margins are impacted. Increasing COGS relative to revenue signifies potential problems that require immediate attention, such as rising prices, inefficiencies, or quality control issues. Conversely, declining COGS as a percentage of sales points to stronger operational performance and higher gross profit margins.

Beyond operational insights, COGS informs pricing, product mix, and growth strategies. When planning investments, companies use COGS data to determine which products deliver strong margins and which may need to be discontinued or reworked. This metric also helps businesses assess the cost-effectiveness of manufacturing products or components in-house or outsourcing production. Additionally, COGS trends can show investors and lenders how effectively management is controlling costs to stay competitive in their market.

What Is the Purpose of COGS?

COGS tracks the direct costs tied to the production of goods sold by a company. This accounting measure is necessary for determining gross profit, guiding pricing strategies, and informing tax calculations. Understanding COGS also helps businesses gauge production efficiency and financial health.

Why Is COGS Important?

COGS provides businesses with insights into the direct costs of their production activities. By analyzing COGS, businesses can make strategic decisions about cost management, product development, and operational improvements, all of which are critical for long-term success and sustainability. The important insights gained from COGS extend into various aspects of business operations, including:

- Profitability analysis: COGS is directly subtracted from revenue to calculate gross profit, which is a primary indicator of a company’s profitability from its core operations.

- Pricing strategy: COGS informs pricing decisions by providing the baseline cost of products, keeping prices competitive to achieve a desired profit margin.

- Tax reporting: COGS is a deductible business expense, which can significantly reduce taxable income, affecting a company’s tax liabilities.

- Inventory management: COGS plays a critical role in inventory accounting, helping businesses understand the cost of inventory sold and manage stock levels efficiently.

- Financial health: COGS is a reflection of a company’s cost management and operational efficiency, which is important for stakeholders, including investors and creditors.

What Is Included in Cost of Goods Sold?

COGS includes all direct costs incurred to create the products a company offers. Most of these are the variable costs of making the product—for example, materials and labor—while others can be fixed costs, such as factory overhead.

A good litmus test to determine whether something should be included in COGS is to ask: Would the cost exist if no products were produced? If the answer is no, then the cost is likely included in COGS.

Examples of costs generally considered COGS include:

- Raw materials

- Items purchased for resale

- Freight-in costs

- Purchase returns and allowances

- Trade or cash discounts

- Factory labor

- Parts used in production

- Storage costs

- Factory overhead

Exclusions From COGS

On the flip side, certain items are excluded from COGS. They include selling, general, and administrative expenses (SG&A), such as:

- Distribution costs to customers

- Office rents

- Advertising

- Accounting and legal fees

- Management salaries

Logically, all nonoperating costs, such as interest and capital expenditures, are excluded from COGS, too. So are the costs for unsold products at the end of a given period. Instead, these are reflected in the inventory on hand at the end of the period.

How to Calculate the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)

Every accountant worth her spreadsheet should be able to rattle off the basic COGS formula in her sleep. On the surface, it’s simple, comprising just three variables: beginning inventory, purchases, and ending inventory. However, layers of complexity underlie each component, requiring several steps to determine their value.

Basic COGS Formula

Here’s the general formula for calculating COGS:

COGS = (Beginning inventory + Purchases) – Ending inventory

Calculating COGS Step-by-Step

Diving a level deeper into the COGS formula requires four steps. Typically, these are tackled by accounting and tax experts, often with the help of powerful software. But these four steps are something all managers should have an appreciation for:

- Identify the beginning inventory of raw materials, then work-in-process and finished goods, based on the prior year’s ending inventory amounts.

- Determine the cost of purchases of raw materials that were made during the period, taking into account freight in, trade, and cash discounts.

- Determine the ending inventory balance. Typically, this number is based on physical cycle counts and done in accordance with the company’s inventory-valuation method of choice.

- Include any other direct costs of production in the valuation of inventory.

COGS and Inventory Counts

As evidenced by the COGS formula, COGS and inventory go hand in hand. For this reason, the different methods for identifying and valuing the beginning and ending inventory can have a significant impact on COGS. Most companies do periodic physical counts of inventory to true up inventory quantity on hand at the end of a period. This physical count is a double check on “book” inventory records. It also helps companies identify damaged, obsolete, and missing (“shrinkage”) inventory.

Once a company knows what inventory it has, leaders determine its value to calculate the final inventory account balance using an accounting method that complies with GAAP.

Companies’ beginning inventory for the current period equals their ending inventory for the prior period, and under GAAP, purchases during each year must be recorded using accrual basis accounting.

Periodic physical inventory and valuation are performed to calculate ending inventory.

Choosing an Accounting Method for COGS

There are many different methods for valuing inventory under GAAP. Different accounting methods will yield different inventory values, and these can have a significant impact on COGS and profitability.

Here are three of the most commonly used methods for valuing inventory under GAAP.

-

First In, First Out (FIFO)

The FIFO method assumes that the oldest inventory units are sold first. It’s an order-of-production approach. This means that the inventory remaining at the end of an accounting period are the most recently produced units. During periods when costs for raw materials or labor are increasing, the FIFO method would yield a higher per-unit valuation of inventory for those items still on hand, compared with those that were sold earlier in the period. In this case, FIFO would cause COGS to be lower.

-

Last In, First Out (LIFO)

LIFO inventory valuation is a reverse-production-order approach. It assumes that the ending inventory on hand are the oldest units produced, and that the newest units produced have already been sold. During periods when costs for raw materials or labor are increasing, LIFO yields a lower per-unit valuation of inventory for those items still on hand, because they were produced earlier in the period. In this case, LIFO would cause COGS to be higher.

-

Average Cost Method (ACM)

ACM values inventory using an average cost for the period. It blends costs from throughout the period and smooths out price fluctuations. Total costs to create products are divided by total units created over the entire period.

Examples of COGS

Consider this simplified example of COGS:

Décor.com sells high-end kitchen tables to consumers. On Jan. 1, 2019, it held five tables in inventory, each valued at $1,000. Then, during the year, Décor.com purchased 10 additional tables from its supplier. On Dec. 31, 2019, Décor.com counted three unsold tables in its warehouse.

Here’s how the company would calculate its costs:

COGS = (Beginning inventory + Purchases) – Ending inventory

So, in Décor’s case:

| Beginning Inventory | $5,000 |

| + Purchases | 10,000 |

| - Ending Inventory | 3,000 |

| = Cost of Goods Sold | $12,000 |

How Is COGS Different From Cost of Revenue and Operating Expenses?

Several other accounting concepts are similar to COGS, but each is different in its own way. Two of the most commonly confused terms are “cost of revenue” and “operating expenses.”

Here’s how they differ:

-

Cost of revenue vs. COGS:

Cost of revenue is most often used by service businesses, although some manufacturers and retailers use it as well. Cost of revenue is more expansive than COGS; it includes not only all the COGS components, but also direct costs in the sales function, such as sales commissions, sales discounts, distribution, and marketing. Similar to COGS, cost of revenue excludes any indirect costs, such as manager salaries, that aren’t attributed to a sale.

-

Operating expenses vs. COGS:

Operating expenses is a catchall term that can be thought of as the opposite of COGS. It deals with the costs of running a business, but not necessarily the costs of producing a product. Operating expenses include selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses, such as insurance, legal and accounting fees, travel, taxes, and office supplies. Excluded from operating expenses are COGS items as well as nonoperating expenses, such as interest and currency exchange costs.

COGS vs. Cost of Revenue vs. Operating Expenses

| COGS | Cost of Revenue | Operating Expenses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What it is | Direct costs associated with the creation of goods sold. Also known as “cost of sales.” | All direct costs associated with producing goods or services for sale. | Day-to-day costs of running a business not included in COGS or cost of revenue. Also known as “OpEx.” |

| What it includes | Raw materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead. | COGS and sales-related costs, such as sales commissions and discounts, distribution, and marketing. | Selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses, such as marketing, payroll, administrative costs, rent, and utilities. |

| Where to find it | Income statement, subtracted from revenue to calculate gross profit. | Income statement, subtracted from revenue to calculate gross margin. | Income statement, listed as expenses to calculate operating income. |

| How to calculate it | COGS = (Beginning inventory + purchases) – ending inventory | Cost of Revenue = COGS + direct selling costs | Operating Expenses = Payroll/wages + sales commissions + marketing/advertising costs + rent + utilities + insurance + taxes |

How to Use Cost of Goods Sold for Your Business

By properly calculating COGS, business managers see the true cost of the products sold. This is critical when setting customer pricing to maintain adequate profit margins.

In addition, COGS is used to calculate several other important business management metrics. For example, inventory turnover—a sales productivity metrics indicating how frequently a company replaces its inventory—relies on COGS. This metric is useful to managers looking to optimize inventory levels and/or increase salesforce sell-through of their products.

COGS is also used to determine gross profit, which is another metric that managers, investors, and lenders may use to gauge the efficiency of a company’s production processes.

Drawbacks and Limitations of COGS

While COGS is a critical measure for understanding a business’s direct costs and profitability, it has its limitations and potential drawbacks, which can affect the accuracy and usefulness of COGS for financial analysis and decision-making:

- COGS doesn’t account for indirect expenses, such as marketing and administrative costs, which can significantly impact profitability.

- Inventory valuation methods can vary, leading to different COGS calculations and making comparisons between companies challenging.

- Because a COGS calculation has so many moving parts, it can be prone to errors and subject to manipulation. An incorrect COGS calculation can obscure the true results of a business’s operations. For example, it can result in misstated net income and tax liability. At the very least, this can lead to wasted time and lost opportunities. At worst, there can be ethical and legal implications.

- COGS is based on historical costs and may not reflect current market conditions or the replacement cost of inventory.

- For service-based companies, COGS may not be as clearly defined or as relevant as it is for product-based businesses.

Tips for Reducing COGS

To reduce COGS, managers must examine every component of their direct costs, from raw material acquisition to quality control processes. The following strategies target the primary drivers of COGS—material, labor, and overhead costs—to reduce waste and strengthen margins. Each approach offers measurable opportunities to lower production expenses without compromising product quality or customer satisfaction:

- Negotiate supplier terms: Regularly review and update contracts with suppliers, often annually or when prices or market conditions change. During renegotiations, focus on cost-saving measures, such as volume discounts, extended payment terms, and delivery schedules. Established partnerships often yield better long-term pricing than constantly switching vendors for marginal savings.

- Enhance quality control: Implement quality checks at multiple production stages to catch defects early, reducing scrap and rework. Invest in proactive detection training and inspection tools to prevent costly downstream mistakes that inflate COGS through high material waste and customer returns.

- Switch to cost-effective inputs: Seek out alternative materials or components that meet quality standards at lower costs. Conduct market research or collect customer feedback to identify different suppliers and inform product redesigns that use less expensive inputs without sacrificing functionality or appeal.

- Reduce inventory waste: Track and minimize damaged, obsolete, or expired inventory through better storage practices and stock rotation. Implement a FIFO system and monitor shelf life with inventory software to help reduce dead stock and COGS.

- Prevent overstocking: Use demand forecasting software and just-in-time inventory principles to avoid tying up capital in excess stock. Overstocking increases storage costs, risk of obsolescence, and inefficiencies when fulfilling orders—all factors that raise COGS.

- Consider lean manufacturing: Apply lean manufacturing principles, such as minimizing unnecessary movements and overprocessing, to eliminate waste in production processes. Techniques like value stream mapping identify non-value-adding activities that increase COGS through inflated labor and overhead costs.

- Cross-train employees: Foster a versatile workforce that can shift between myriad tasks as demand fluctuates. Proactive cross-training reduces idle time, cuts overtime costs, and increases productivity, directly lowering the labor component of COGS.

- Utilize technology: Deploy manufacturing software, automation, and data analytics to optimize scheduling and reduce manual data entry and errors. ERP systems integrate companywide data to provide real-time visibility into costs throughout the production cycle, helping managers identify opportunities to reduce COGS.

Cost of Goods Sold and Tax Returns

So far, this discussion of COGS has focused on GAAP requirements, but COGS also plays a role in tax accounting. Businesses that hold physical inventory—such as manufacturers, retailers, and distributors—are required to calculate COGS when determining their taxable income.

This tax calculation of COGS includes both direct costs and parts of the indirect costs for certain production or resale activities as defined by the uniform capitalization rules. Indirect costs to be included for tax purposes include rent, interest, taxes, storage, purchasing, processing, repackaging, handling, and administration. For detailed worksheets, see IRS Publication 334 (opens in new tab); for most managers, however, it’s sufficient to understand that this expanded calculation of COGS typically decreases the total tax bill.

For businesses with under $30 million in gross receipts (as of 2024), there are some exceptions to the rules for inventory, accrual accounting, and, by extension, COGS.

Cost of Goods Sold and Accounting Software

Calculating COGS can be challenging. It requires a company to keep complete and accurate records for the GAAP calculations reported on financial statements and, separately, to support a tax return. A company’s inventory management, from both the physical and valuation perspectives, must be precise. Purchases and production costs must be tracked during the year.

And regardless of which inventory-valuation method a company uses—FIFO, LIFO, or average cost—much detail is involved.

All of the above can become exponentially more complicated when volumes and product lines increase. For companies with many SKUs, the best approach to calculating COGS is a robust accounting system integrated with inventory management.

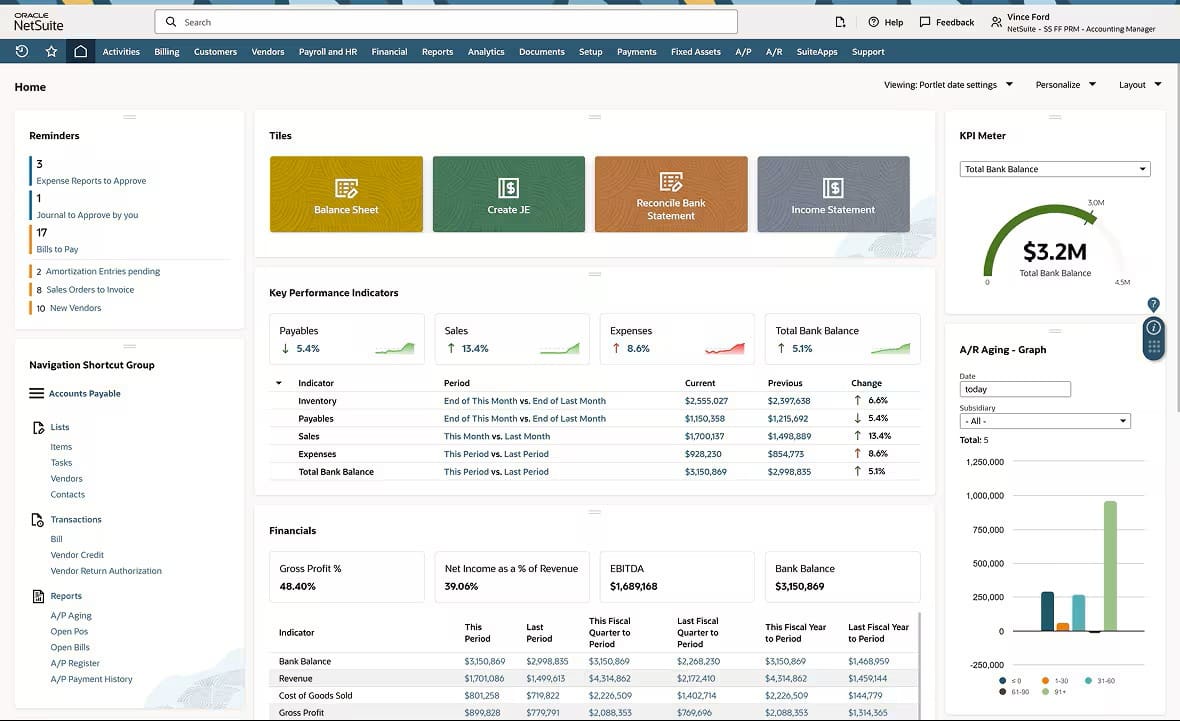

Calculate Your COGS With NetSuite

NetSuite Cloud Accounting provides businesses with a comprehensive, real-time view of their financials for accurate COGS calculation. The software supports automated data entry and accounting processes to reduce errors that can affect COGS, gross profit, and, ultimately, financial statement accuracy. Integration with other business systems, such as NetSuite Inventory Management, unlocks detailed tracking of inventory levels, purchases, and production costs, to feed into the COGS. By integrating between sales, inventory management, and overall financial management, NetSuite gives businesses the insights they need to manage COGS effectively.

NetSuite’s Accounting Dashboard

Knowing your COGS is critical to achieving and sustaining profitability, so it’s important to understand its components and calculate it correctly. COGS also reveals the true cost of a company’s products, which is important when setting pricing to yield strong unit margins.

COGS FAQs

Is cost of goods sold an expense or revenue?

Cost of goods sold is an expense, representing all of the direct costs a company incurs in the production and sale of its products and services. Costs include raw materials, direct labor, and storage.

How do you record cost of goods sold?

Cost of goods sold (COGS) is recorded as an expense on the income statement and is subtracted from revenue to determine gross profit. Meticulous recordkeeping on inventory and purchases is essential for COGS to be calculated accurately.

Where do COGS go on a balance sheet?

Cost of goods sold (COGS) doesn’t appear on a company’s balance sheet. Rather, it’s found on the income statement. COGS is one of the variables for calculating gross profit, which does appear on the balance sheet.

What is cost of goods sold in P&L?

Cost of goods sold is a line item on a business’s profit and loss (P&L) statement, which also includes its revenue, expenses, interest, taxes, and net income. The P&L provides insight into the company’s profitability for a set accounting period.