At the end of 2000, an ounce of gold was worth $275. At the end of 2024, that same ounce was worth $2,609. Investors who held on to their gold for 24 years experienced appreciation—the increase in value of an asset over time. However, until the gold is actually sold, this appreciation is just theoretical, or, as accountants would say, “unrealized.” For example, if a sale was made on New Year’s Eve 2024, at the going rate, investors would have realized asset appreciation and pocketed a hefty return. Businesses encounter similar situations when they buy and hold certain assets and then are faced with how to handle their increase in value in keeping with prevailing accounting standards. This article aims to explain appreciation, how to account for it in the company’s financial statements, and the implications that come with it.

What Is Appreciation in Accounting?

Understanding appreciation is crucial for businesses and investors as it can significantly impact financial decisions, tax planning, and overall asset management strategies. In accounting, appreciation refers to assets becoming more valuable over time. Similar to the gold example, many types of assets—land, patents, investments—can increase in value for various reasons, such as market conditions, scarcity, or inflation. Not all assets appreciate, however. Appreciation applies to long-term assets that a business plans to use or hold, but not to inventory or other assets intended for sale in the normal course of business. Some business assets, such as equipment and vehicles, actually lose value through wear and tear, a process known as depreciation (more on that later).

Under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), businesses must record assets at their original purchase price, regardless of any increase in market value, although there are a few exceptions in the financial services and agricultural industries. This means that for most businesses, a building purchased for $1 million five years ago remains on the books at $1 million, even if its market value has doubled. The appreciation only appears on financial statements when the asset is sold and the gain is realized. GAAP’s conservative approach differs from International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), which give international companies an option to periodically revalue certain assets to reflect their current market value. For further information on IFRS, consult International Accounting Standard (IAS) 16, IAS 40, and IFRS 9. This article discusses appreciation under GAAP standards.

Key Takeaways

- Appreciation is an increase in asset value caused by external market forces.

- Under GAAP, appreciation stays off the books until realized through a sale.

- Strategic management of appreciated assets improves profitability and borrowing power.

- Best practices and various valuation methods help businesses track and benefit from asset appreciation.

- Managing and tracking asset appreciation require well-structured, automated financial management tools.

Appreciation Explained

Appreciation refers to an increase in an asset’s inherent value without involving any direct action or improvement by its owner. Unlike revenue generated from business operations, appreciation occurs passively, often influenced by market dynamics and broader economic trends. The simplest example is supply and demand: When more people want something that’s in limited supply, its price goes up. This is common in real estate in growing cities.

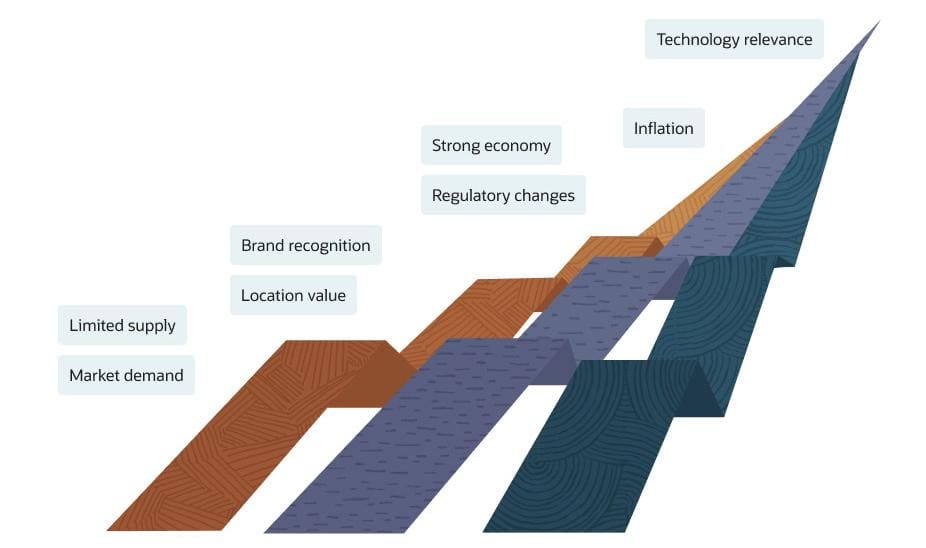

Inflation also contributes to appreciation, as rising prices across the economy drive up asset prices over time, which is why many investors buy real estate or precious metals (like our gold example) to protect their wealth. Other factors that cause appreciation include a strong economy, perceived changes in what an asset is worth, and new laws or regulations. Think of a commercial building whose value increases because the neighborhood around it improved with new roads and businesses. Or consider a patent that becomes more valuable because the technology it protects suddenly becomes popular in the market. Two types of assets that commonly experience appreciation are:

- Fixed assets: These are long-term, physical assets that a business owns and uses in its operations, such as land, buildings, and equipment. Within these categories, land often appreciates due to location, development of surrounding areas, or increased demand. However, under GAAP, any increase in value remains unrecognized on financial statements until the property is sold.

- Intangible assets: These are nonphysical assets that have long-term value, such as patents, trademarks, copyrights, brand names, and customer lists. These assets can appreciate significantly as their market relevance grows, such as when a patented technology gains wider adoption or a brand name becomes more recognized in the marketplace. Like fixed assets, the increased market value of intangible assets is generally not reflected in financial statements until realized, such as through a sale or licensing agreement.

Asset Appreciation Drivers

Is Appreciation the Same as Capital Gain?

Appreciation and capital gains are different, but related, concepts. A capital gain occurs when an asset is sold for more than its original purchase price or book value. While appreciation represents the increase in an asset’s value over time, it’s considered an unrealized gain until the asset is sold, at which point it becomes a realized, or capital, gain. For example, if a company buys shares of stock for $10,000 and sells them years later for $15,000, the $5,000 profit is a capital gain because it represents the appreciation that has been captured through the sale.

The discussion of capital gains is especially important when it comes to tax liability. Under U.S. tax law, this type of appreciation is typically subject to a special capital gains tax, though the treatment varies by business entity type and asset nature. While C corporations pay the same tax rate on capital gains as ordinary income, pass-through entities—S corporations, partnerships, and most LLCs—can allow capital gains to flow through to owners’ individual returns, potentially qualifying for preferential rates based on the owner’s tax situation and asset holding period.

Appreciation Examples

To illustrate how appreciation works, let’s consider a few real-world scenarios. Appreciation can unfold gradually over time or accelerate rapidly, depending on market forces and economic conditions. Its rate and pattern often differ based on the asset type, prevailing market trends, and external influences. Here are some examples of appreciation.

- A piece of real estate purchased for $200,000 appreciates gradually to $250,000 over 20 years as the surrounding area slowly develops.

- A painting bought for $50,000 appreciates to $100,000 in just months following the artist’s popular museum exhibition.

- Shares of stock acquired at $50 per share appreciate to $75 per share as the company grows and becomes more profitable.

Benefits of Appreciation in Accounting

To fully reap the benefits of appreciation, it’s important for CFOs, financial leaders, and business owners to understand the accounting treatment and practical implications involved. For example, although the appreciation of intangible assets may not be directly reflected in financial statements, it can significantly impact a company’s overall market value. Investors and analysts often consider the potential value of intangible assets when evaluating a company, even if this value isn’t explicitly stated on its balance sheet. The same goes for potential lenders that may consider the current market value of assets when evaluating collateral, rather than just their book value. Benefits of appreciation include:

- Improved profitability: When a company sells an appreciated asset, the realized gain increases profitability and cash flow, resulting in improved financial performance. Additionally, appreciated assets strengthen a company’s financial profile and may lead to increased borrowing capacity and better lending terms.

- Potential tax advantages: While unrealized appreciation isn’t taxable, strategic timing of asset sales can help businesses optimize their tax position. Under U.S. tax laws, companies can defer recognizing gains by holding on to appreciating assets, allowing them to control when taxes on realized gains are due. This strategy makes it possible for businesses to align asset sales with years when offsetting tax losses are available.

- Improved financial visibility: Knowledge is power. Regular monitoring of asset worth keeps management informed of the level of untapped value in asset appreciation. This crucial information empowers business leaders to make more informed decisions about resource allocation, investment strategies, and whether to hold, sell, or leverage appreciating assets for business growth.

Accounting for Appreciation

As we’ve established, appreciation occurs when an asset’s market value exceeds its original purchase price or book value, making it essential for accountants to track both. Although appreciation isn’t recorded under GAAP, companies can still measure and monitor it using various methods. In practice, businesses typically use a combination of methods to assess market value and gain a comprehensive understanding of asset appreciation, including:

- Professional appraisals: Engage certified appraisers to periodically assess the current market value of significant assets, especially real estate and collectibles.

- Market analysis: Regularly review market trends and comparable sales for similar assets in the same geographic area or industry. This is particularly useful for stocks, bonds, or precious metals.

- Income approach: For income-generating assets, estimate their present value by predicting the cash flows the asset is expected to generate in the future. For example, you could measure the expected future royalties from intellectual property assets.

- Cost approach: Calculate an asset’s current value by determining the replacement cost of a new asset with equivalent functionality, then subtract the estimated value lost from age, wear and tear, and obsolescence. This approach is commonly used when comparable market data isn’t available or applicable, as might be the case for assets such as customized machinery or specialized equipment.

- Automated valuation models: Employ software that analyzes public record data and recent sales of comparable assets to estimate current value using algorithms and statistical models, instead of a physical appraisal. This is especially useful for personal and commercial real estate.

- Insurance valuations: Review insurance coverage and associated asset valuations, which are often updated regularly. Assets, such as heavy machinery and art collections, are often valued using this method.

- Tax assessments: Consider property tax assessments, which can provide a baseline for tracking value changes over time, for land holdings and commercial buildings. Be aware that tax assessments aren’t always reflective of true market value.

- Internal expertise: Leverage knowledge of internal experts who understand the asset and its market. This approach may be useful for assets developed in-house, such as customized software, or those with no historical cost but some external value, such as internally developed brands or trademarks.

How to Calculate the Appreciation Rate

The appreciation rate measures the percentage increase in an asset’s value over a specific time period. It’s useful for evaluating investment performance and comparing assets’ growth potential. The appreciation rate is one factor used to assess whether assets are meeting expected returns and to identify which assets might be candidates for strategic sale or refinancing opportunities. The most basic way to calculate the appreciation rate is to subtract an asset’s original value from its current value, divide by the original value, and multiply by 100. The formula is:

Appreciation rate = [(Current value – Original value) / Original value] x 100

For example, if a company purchased a commercial property for $500,000 five years ago and it’s now worth $650,000, the appreciation rate would be 30%, calculated in this way:

Appreciation rate = [($650,000 – $500,000) / $500,000] x 100 = 30%

This means the property has appreciated by 30% over the five-year period, or by an average of 6% per year.

However, some finance professionals opt for a more sophisticated approach that uses the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for more precise year-over-year comparisons. This way of calculating the appreciation rate is more accurate for assets that have been held for longer periods of time and for comparing assets with different holding periods. The CAGR formula is as follows, with “n” being the number of years:

CAGR = (Ending value / Beginning value)^(1/n) – 1

Using the same example as above, the appreciation rate for the commercial property would be calculated as:

CAGR = ($650,000 / $500,000)^(1/5) – 1

= (1.3)^(0.2) – 1

= 1.0537 – 1

= 0.0537 or 5.37%

The CAGR is 5.37%, meaning that if the asset had grown steadily at this rate each year, its value would have increased from $500,000 to $650,000 over five years. This differs slightly from the simple average of 6% per year because CAGR accounts for the compounding effect over time, making it a more accurate measure of year-over-year growth.

How to Record Appreciation: Example

The following example shows the step-by-step accounting process for appreciation. Note the timing of each journal entry, since the gain won’t be recognized until the time of sale.

TechMed Solutions, a fictional healthcare software company, purchased a patent for an innovative patient monitoring algorithm on Jan. 1, 2020, for $100,000. At the time of purchase, the technology was promising, but untested in the market.

To record the initial purchase Jan. 1, 2020:

| Debit | Credit | |

|---|---|---|

| Patents (Intangible asset) | $100,000 | |

| Cash | $100,000 | |

| To record purchase of patient monitoring algorithm patent at cost. | ||

By December 2023, the healthcare industry had widely adopted remote patient monitoring due to changing healthcare delivery models. Though TechMed’s internal valuations showed the patent’s market value had increased to $250,000, to comply with GAAP the patent remained on the books at its original cost of $100,000, less $40,000 accumulated amortization (the process of allocating the cost of an intangible asset over a specific period). When purchased, the patent had an estimated useful life of 10 years. TechMed amortized it using the straight-line method, like so:

To record annual amortization in each of the four years (2020-2023):

| Debit | Credit | |

|---|---|---|

| Amortization expense | $10,000 | |

| Accumulated amortization | $10,000 | |

| To record annual amortization: $100,000 / 10 years = $10,000 per year. | ||

In June 2024, a large medical device manufacturer acquired the patent for $250,000 to integrate the algorithm into its new line of monitoring devices. TechMed recorded the sale as follows, starting with updating amortization:

To update amortization through June 2024:

| Debit | Credit | |

|---|---|---|

| Amortization expense | $5,000 | |

| Accumulated amortization | $5,000 | |

| To record six months of amortization: $10,000 per year x (6/12) = $5,000. | ||

To record the sale of the patent June 30, 2024:

| Debit | Credit | |

|---|---|---|

| Cash | $250,000 | |

| Accumulated amortization | $ 45,000 | |

| Patents | $100,000 | |

| Gain on sale of patent | $195,000 | |

| To record the cash sale of the patent and recognize the realized gain. | ||

The sale of TechMed’s patent for its patient monitoring algorithm would have a significant impact across each of the company’s financial statements.

- On the balance sheet of June 30, 2024, the transaction results in a notable shift in assets. The patent’s value, previously listed at its net book value of $55,000 (original cost of $100,000 minus accumulated amortization of $45,000), would be removed. In its place, cash would increase by $250,000, reflecting the sale proceeds. The company’s equity would also increase by $195,000, due to increased net income from the gain on the sale.

- On the income statement for the six-month period ending June 30, 2024, TechMed would report a “gain on sale of patent” of $195,000 under “other income.” This one-time gain would boost both operating income and net income for the period.

- The statement of cash flows for the six-month period ending June 30, 2024, would reflect this transaction in the investing activities section, showing a cash inflow of $250,000 from the proceeds of the sale.

- In the notes to the financial statements, TechMed would provide additional details on the transaction, if that’s material. The notes would likely include a description of the patent sold, its original cost and accumulated amortization, the sale price, and the resulting gain. The company might also explain the strategic rationale behind the sale and any ongoing relationships with the buyer.

- In TechMed’s annual report, in the Management Discussion and Analysis, or MD&A, section, the company would offer further insights into the transaction’s significance, such as the factors that led to the patent’s appreciation, how the sale aligns with TechMed’s strategic objectives, the impact on its financial position and future operations, and plans for using the sale proceeds.

Appreciation in Accounting Best Practices

Managing asset appreciation requires a balanced approach between accounting requirements and practical business needs. Here are six best practices to help businesses track and benefit from appreciating assets.

- Always record the original cost of the asset. Maintain accurate records of initial purchase price, including all acquisition costs related to putting the asset into service, such as transportation, and installation. This historical cost serves as the baseline for measuring future appreciation and ensures compliance with GAAP requirements.

- Understand how asset type impacts its appreciation rate. Different assets appreciate differently—real estate might increase steadily with market conditions, while patents or intellectual property could surge in value in step with technological breakthroughs or market adoption.

- Review the value of your assets regularly. Implement a systematic process for monitoring asset values, even though appreciation isn’t recorded on financial statements. Regular valuations help identify opportunities for strategic sales or refinancing and also ensure adequate insurance coverage.

- Consider whether appreciation has any tax repercussions. Plan strategically for potential tax implications when appreciated assets are sold. Understanding tax consequences helps businesses time asset sales advantageously and prepare for resulting tax obligations.

- Follow all applicable accounting standards when recording. Maintain compliance with relevant accounting frameworks, such as GAAP or IFRS, that dictate how to handle initial asset recognition, subsequent revaluation, and disclosure requirements. For example, although GAAP generally requires historical cost reporting, certain industries, such as financial services, may need to use fair value accounting for specific assets. Understanding these nuances ensures accurate financial reporting and helps avoid regulatory issues.

- Report any necessary disclosures appropriately. Consider including relevant information about significant appreciated assets in the notes to the financial statements, even when appreciation isn’t recorded on the balance sheet. This transparency helps stakeholders understand the company’s true financial strength and potential future economic benefits. Even though such disclosures are often voluntary, they align with GAAP’s full disclosure principle of providing relevant and reliable information to financial statement users.

Appreciation vs. Depreciation

Appreciation and depreciation both involve changes in asset value over time, but they move in opposite directions and are treated differently in accounting. As we’ve established, appreciation represents an increase in an asset’s value that occurs because of external market forces. In contrast, depreciation reflects the systematic allocation of a tangible asset’s cost over its useful life, recognizing a decline in value from use, wear and tear, or obsolescence. Similarly, amortization serves the same purpose for intangible assets, spreading their cost over their expected useful life.

The accounting treatment for these value changes differs significantly. Under GAAP’s cost and conservatism principles, potential losses or declines in value must be recognized immediately through depreciation or amortization expenses, reducing both the asset’s book value and the period’s net income. However, appreciation generally remains unrecognized in financial statements until the asset is sold, with few exceptions, as mentioned previously in this article. This conservative approach ensures that financial statements don’t overstate asset values or company worth.

Simplified Reporting With NetSuite Cloud Accounting Software

NetSuite cloud accounting software provides real-time visibility into asset book values, automated depreciation and amortization calculations, and comprehensive financial reporting capabilities. The fixed asset management module helps businesses maintain detailed asset records, from acquisition costs to improvement expenses, while tracking market valuations and potential appreciation. With customizable dashboards and detailed audit trails, businesses can better monitor their appreciating assets, maintain accurate historical records, and generate the detailed reports needed for sell/hold decisions, financial statements, and stakeholder communications.

Just as gold investors need to understand how appreciation affects their investments, businesses must also manage the implications of asset appreciation. Although unrealized appreciation is barred from financial statements under GAAP, once realized, these gains can significantly impact a company’s financial results, tax liabilities, and capital gains. Appreciation is a valuable, untapped resource that businesses can strategically use to increase profitability, optimize tax planning, and secure better borrowing terms. To fully capitalize on the benefits of appreciation, companies should implement accounting software and asset tracking systems, use accurate valuation methods, and adhere to proper accounting practices. Doing so enables businesses to turn theoretical asset growth into tangible financial gains while guaranteeing compliance and long-term stability.

Appreciation in Accounting FAQs

How does appreciation impact a company’s financial statements?

Under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), appreciation generally doesn’t appear on financial statements until an asset is sold, at which time the appreciation is recorded as a gain on the income statement. This, in turn, increases net income on the income statement and equity on the balance sheet. The cash received from the sale appears on the balance sheet and in the cash flow statement under investing activities. Then, the sold asset is removed from the balance sheet.

Where is appreciation recorded on a balance sheet?

Under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), unrealized appreciation typically isn’t recorded on the balance sheet, as most assets are carried at original purchase price minus accumulated depreciation or amortization. However, when an appreciated asset is sold, it’s removed from the balance sheet and the resulting gain increases the company’s cash or receivables and equity.

Is appreciation considered income?

Appreciation isn’t considered income until it’s realized through a sale. Until then, it represents an unrealized gain that isn’t reflected in the company’s financial statements. Once realized through a sale, asset appreciation becomes a taxable gain reported on the income statement.

Is appreciation considered an asset or a liability?

Appreciation itself is neither an asset nor a liability; it represents an unrealized increase in an existing asset’s value. When an asset is sold, its appreciation is realized, increasing the company’s assets (usually cash) and equity.