In short:

- To determine the price of a subscription, companies can start with three methods as a basis for their calculations.

- Cost-plus, competitor-based and value-based pricing are all methodologies that can serve as the foundation for determining the price of a product or service.

- While all pricing methods have their places in business, the thorough approach used by value-based pricing tends to be the best option for subscriptions.

You’re reading part V of a series.

Part I: Subscription Pricing Models

Part II: Pricing Strategies

Part III: Subscription Model Q&A

Part IV: Psychological Pricing Tactics

For those who have come along on this Odyssey-like journey through the intricacies of subscription models, strategies and psychological tactics, we have reached our last stop: a breakdown of pricing methods.

As we voyaged through models and strategies, a question may have popped into your head: “Well great. Now I know how to structure and optimize my pricing. But how exactly do I determine how much my offering should cost?”

The answer lies in the methodologies companies use to decide the “just right” price of a given product or service. Cost-based pricing, competitor-based pricing and value-based pricing are the three methods used for both subscription and traditional ownership models. Each presents a unique way for your business to set the actual numbers behind a price.

Cost-Plus Pricing

Definition: Also referred to as “markup pricing,” companies using cost-plus pricing add a specific markup to a product’s unit cost. It is considered the simplest way to determine price.

How to use: Calculate the fixed and variable costs of doing business, add a percentage margin and voila — that’s the price.

Costs + Profit Margin = Price

Best for: Cost-plus pricing tends to work well for manufacturing companies when the products they create have relatively predictable fixed costs. These businesses may sell products in bulk, repetitively, to existing customers, making it easier to build a predictable revenue stream and maintain margins. Markup pricing also works well in contractual situations where the supplier has little downside risk.

If you calculate cost of goods sold (COGS), it’s relatively easy to assign a profit margin percentage that sustains the business. However, cost-plus pricing works less well in situations where there is heated competition, supply chain cost volatility or in certain business types.

For instance, in competitive market situations, a company may need to accept slimmer margins to stay in the running, and when raw material costs fluctuate significantly, pricing would need to be constantly retooled. Markup pricing also tends to be problematic for SaaS companies. Oftentimes, unless fixed costs are high, the costs for delivering a single account of a software-as-a-service product can be very low — meaning the costs of paying developers are not necessarily reflective of the value the customers get out of the service. To maximize revenue, services in particular need to be evaluated from that value perspective, not just on the inherent costs of the product itself.

Tip: Cost-plus tends to be a good starting point for companies to determine the lowest possible price — it is less well-suited as a permanent or standalone method.

Example: A subscription shaving company sends its subscribers razor cartridges every month.

The total production cost is $8,250,000. To find the cost per unit, divide the production cost by the production volume:

8,250,000/3,500,000 = approximately $2.36 per unit

The company sends a pack of four razors to its subscribers monthly, which costs the company $9.44 per unit. However, the company adds a 38% markup, making the cost about $13 per month.

Advantages of cost-plus pricing:

- Simplest method

- Requires little to no market research, customer feedback or other analysis

- Predictably covers costs and yields an easy-to-justify price

- Can determine the lowest possible price a company can charge and still operate profitably

The bottom line: Cost-plus pricing is best for a company in a non-competitive market that offers a physical product with stable COGS.

Competitor-Based Pricing

Definition: A competitor- or competition-based strategy uses competitors’ pricing as the benchmark. After determining the competition’s prices, a company can choose to offer a lower, higher or matched price.

How to use: Identify competitors, research their pricing and positioning and map out your strategy. Determine whether your company wants to offer a lower, higher or matched price.

Best for: In any market, knowing where competitors are in terms of pricing is integral to determining how to position your product. So continually tracking what your rivals are charging, as closely as possible, is a good practice for all companies.

However, simply conducting this exercise and then matching the going rate can lead to missed opportunities to maximize revenues and profits and highlight your company’s unique value. Each business is unique — and the pricing process should reflect that.

Tip: Be cognizant of your competitor’s pricing, but don’t base your entire strategy on it.

Example: A short-term flex office space provider is looking to price a suite that fits up to 40 people and includes access to two conference rooms. One of its competitors in the area offers a similar suite for $45,000 per month. Another prices its office suite at $43,000 per month. With that in mind, the company opts to price its suites at $43,000 per month to match the lower-priced competition.

Advantages of competitor-based pricing:

- Simple to gauge through basic research of competitors

- Allows companies to send a message of better value or of higher quality by going lower or higher than their competitors — or similar in quality and value by price-matching

- Ability to be dynamic when competitive pricing analysis is performed at a regular cadence. There are companies that raise and lower prices based on market trends, though customer acceptance needs to be considered.

Requirements: Best for companies in ultra-competitive markets — like the retail space — where having pricing in line with competitors is integral.

Value-Based Pricing

Definition: The value-based pricing method uses a customer’s perceived value of a product or service as the basis for pricing.

How to: Value-based pricing boils down to determining what a customer is willing to pay. First, conduct extensive research into your target audience. Use that information to set prices. In some situations, the concept of economic value to the customer will be helpful to determine what a customer will pay for a product or service that delivers value in excess of its closest competitor.

“Willingness to pay” refers to the maximum price a customer is willing to pay for a product or service. Also known as the economic value to the customer, true economic value is the amount a customer will pay for a product or service that delivers value in excess of its closest competitor. It is calculated through the formula:

TEV = cost of the best alternative + value of performance differential

“Economic value to the customer (EVC)” gauges how much value — both tangible and intangible — a customer gets from using a product or service. It is calculated through the formula:

EVC = Tangible value the product provides + Intangible value the product provides

Examples: For instance, consider the iPhone. According to Investopedia, the iPhone 11 Pro Max has the following cost breakdown:

- Screen: $66.50

- Battery: $10.50

- Triple camera: $73.50

- Processor, modems and memory: $159

- Sensors, holding material, assembly and other: $181

The cost of all the phone components add up to about $490.50, though this does not include costs like research and development, marketing and other overhead. However, the phone cost $1,099 when launched.

Meanwhile, the Galaxy S10, a phone with similar functionality launched by Samsung in the same year, had similar costs to build but went for $899 at its highest price point. While both are providing the same tangible value — a smartphone — Apple is able to charge more because of its intangible value. It knows its customers are willing to pay more for the brand recognition, software and “cool factor” associated with its devices.

Additionally, Apple provides a convenience that can be considered both a tangible and intangible factor. For those who have contacts who also have iPhones, messages can be sent via Apple’s iMessage technology — the coveted blue texts. If not, messages will be sent via SMS — the dreaded green. Tangibly, communicating over iMessage is cheaper than SMS and can be done internationally, resulting in measurable and quantifiable cost savings. The intangible value: being able to communicate with friends and family more easily.

As another example, let’s look at a hypothetical subscription car company based in Chicago that costs $500 per month per subscriber. For customers, there are clear tangible benefits: Use of a midsize car worth $25,000, and the company includes insurance and reserved parking spots around the city. On average, for those living in downtown Chicago, those cost about $100 and $200, respectively.

However, there are also intangible benefits, like having a car when you want one, the ability to request a different style of car based on need, driving a new car at all times instead of depreciating one, the peace of mind of not being liable for any damage or theft that occur when the car is in its reserved parking spot, and not responsibility for maintenance; the latter two of which could also be considered quantifiable tangible values based on the average lifetime costs associated with owning a car.

The costs the customer incurs to purchase the product is subtracted from the EVC to get the absolute EVC. A positive absolute EVC is good — the customer has incentive to buy your product or service. A negative absolute EVC? Not so much.

Depending on the company and product, the process to determine the range of a customers’ willingness to pay, true economic value and economic value to the customer could take many forms, with many businesses opting for one — or several — of the following:

- Customer feedback: Whether qualitative or quantitative, open ended or fixed choice, planned or spontaneous, customer feedback can be compiled to help gauge a willingness to pay.

- Business metrics: Know critical KPIs like your unit economics, customer lifetime value (LTV) and customer acquisition costs. A good price won’t be so good for your company if it doesn’t take into account real production or service delivery costs. Hint: A good lifetime value to customer acquisition cost ratio is 3:1. If you don’t have those numbers yet, examine competitor pricing to guesstimate their costs and build from there.

- Surveys: Surveys should ask current and target customers questions

around your core services and products, add-on features, what value your products

deliver to them and what they are willing to pay.

Common tools used in these surveys include:- Price sensitivity tests: Many companies will use some form of

a pricing sensitivity tool, like Van Westendorp's Price Sensitivity Meter, to

determine customer price preferences. These tools usually ask four price-related

questions that go something like this:

- What price would be so low that you start to question this product’s quality?

- At what price do you think this product is starting to be a bargain?

- At what price does this product begin to seem expensive?

- At what price is this product too expensive?

- Conjoint Analysis: This method breaks down a product or offering into its components and then asks users to compare or rank the features to determine how much they value each one. This is especially helpful if a company is considering something like a tiered subscription model because it will show which features can be assigned to a higher-priced tier and which are best grouped in lower ones.

- Price sensitivity tests: Many companies will use some form of

a pricing sensitivity tool, like Van Westendorp's Price Sensitivity Meter, to

determine customer price preferences. These tools usually ask four price-related

questions that go something like this:

- Focus groups: These are particularly useful when qualitative feedback is desired from the target audience because groups allow for freeform discussion.

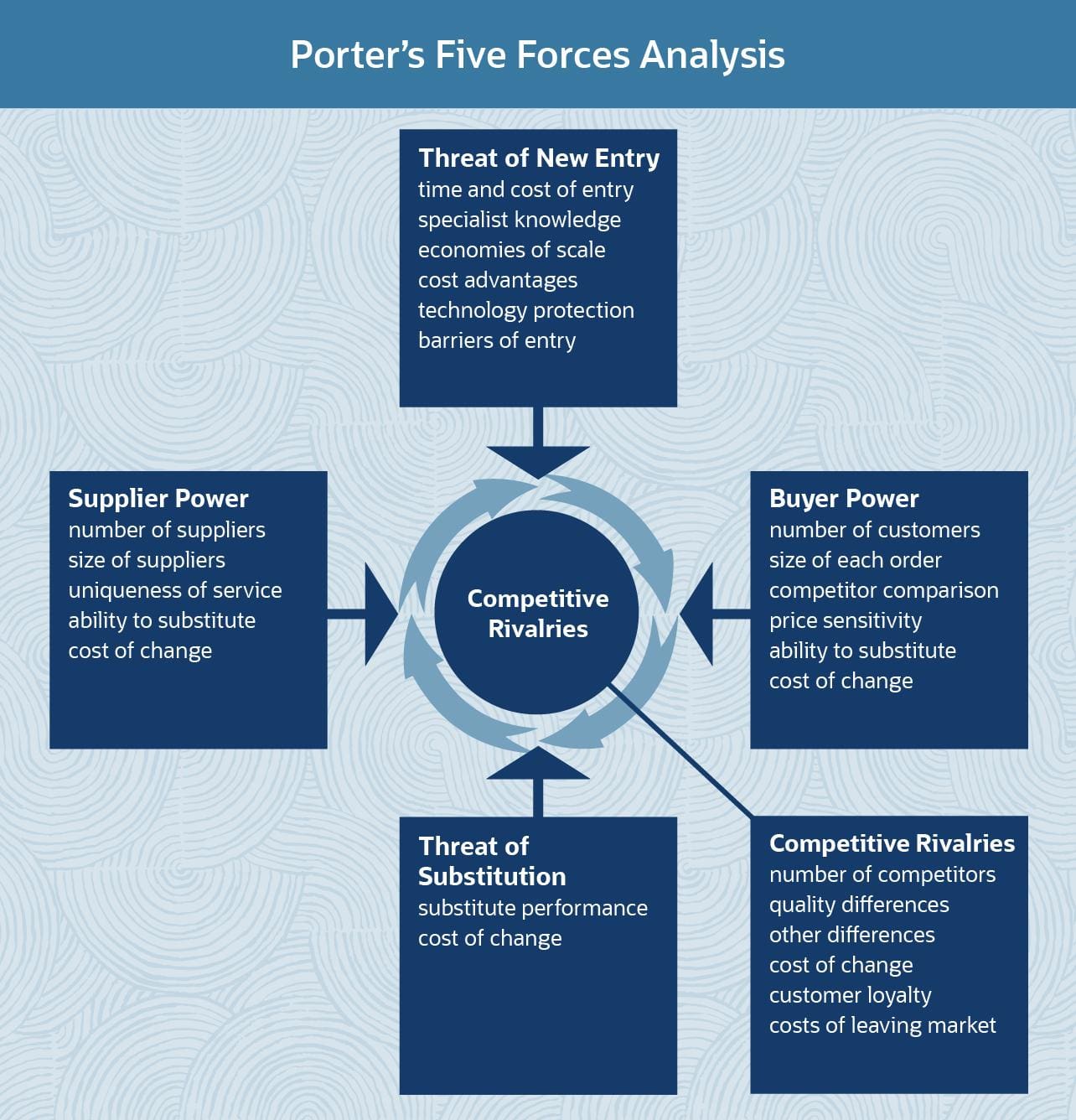

- Industry analysis: Consider Porter’s Five Forces (below) around competitive rivalry, the threat of new entrants, the threat of substitution, buyer power and supplier power.

- Market research: This effort encompasses various types of important information-gathering steps, like competitive analysis, market segmentation, trendspotting and risk analysis, that can impact pricing.

- Buyer personas: A culmination of much of the preceding information-gathering results, buyer personas are semi-fictional profiles of your ideal customers.

Requirements: Value-based pricing is ideal for products or services that have clear value differentials from the competition. If a product is similar to its competitors, people aren’t likely to pay more than the competitor is charging — which makes competitor-based pricing an easier and less time-intensive option. Perhaps the biggest gatekeeper to the value-based pricing strategy is how willing and able a company is to invest in determining the product price since this method requires more time and resources than any other pricing method.

Tip: It may be resource-intensive, but value-based pricing tends to be the most well-rounded method, particularly for a subscription offering where the value is rooted in the service./p>

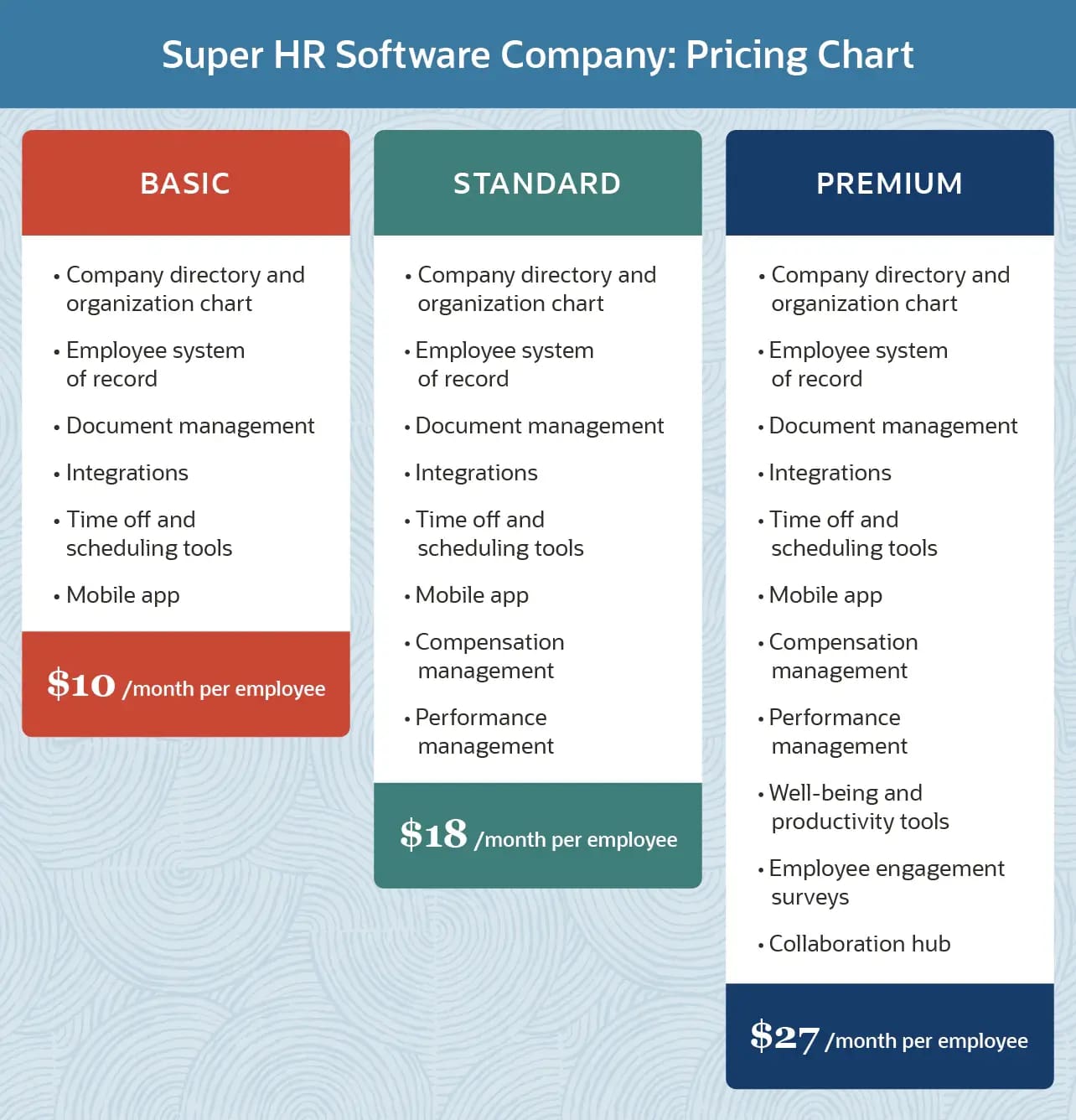

Example: A human resources software provider conducts extensive research into its customer base and total addressable market. It also conducts a conjoint analysis to understand the value of its features. Based on that information, it builds three buyer personas.

Based on the research, feedback and ensuing buyer personas, the human resources software company splits its pricing into three tiers, with the top two options priced higher based on the value the extra features deliver and how much those customers are willing to pay.

Advantages of value-based pricing:

- Increased focus on customer service, which can produce multiple benefits

- If customers have a high willingness to pay, the product can have a higher price point

- Perceived value can increase

- Taps into customers’ priorities, making it easier to sell new, profitable features and upgrades

Requirements: Significant time investment and strong relationships with customers to figure out customer valuations, which is a continual process.

Demand-Based Pricing

A variant of value-based pricing, demand-based pricing also takes into account what a customer is willing to pay, but the price fluctuates based on demand. A prime example? The airline industry dynamically changing flight prices based on the volume of travelers looking to fly on certain dates to certain locations.

The Bottom Line

Ultimately, each pricing method has its place. The challenge is knowing which one, or combination, is best for your company. For instance, with its price-match guarantee, Walmart is pretty much pigeon-holed into competitor-based pricing. Grocery stores thrive on cost-plus pricing because they sell products, not services, and they buy repetitively in bulk. However, in most subscription situations, value-based pricing will be the best bet. Subscriptions are providing a service to their customers — an ideal price will take the value that the service provides its buyer into account. While value-based pricing is more complicated than its competing methodologies, having an informed pricing method is worth the extra effort for subscription offerings.

Check back for our concluding piece in this subscription pricing series, on how to bring all the components — models, strategies and methods — together into a comprehensive subscription pricing approach.

For more helpful information from the Brainyard and our friends at Grow Wire and the NetSuite Blog , visit the Business Now Resource Guide.