A balance sheet is a foundational document that provides important insights into a company’s financial health at a particular moment in time. Unfortunately, for those without accounting expertise, balance sheets can sometimes feel indecipherable. For nonprofit organizations, understanding a balance sheet can be even more difficult, due to specialized nonprofit accounting rules that are slightly different from the rules for-profit companies must follow. Because nonprofit corporations are driven by a mission, not monetary profit, and rely on the support of donors to achieve their goals, nonprofit balance sheets reflect an extra level of transparency designed to highlight any assets encumbered by donor restrictions.

This article explains the unique rules for nonprofit balance sheets, including how they classify assets and liabilities and how they differ from for-profit balance sheets. In addition, it explores how to read a balance sheet to interpret what it says about a nonprofit organization’s financial health.

What Is a Nonprofit Balance Sheet?

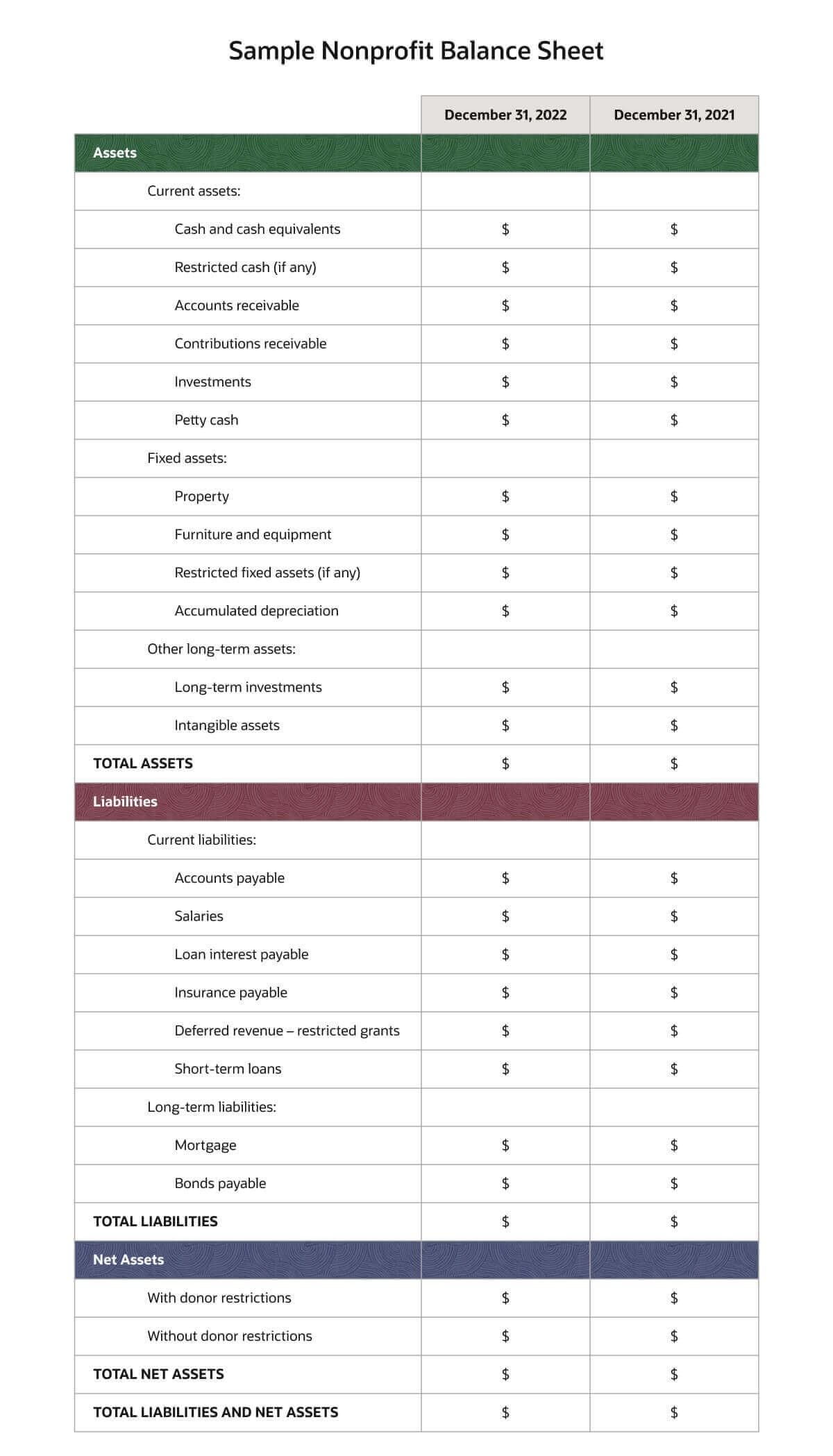

A nonprofit balance sheet is technically known as a statement of financial position. It provides a detailed overview of a nonprofit’s financial health at a specific moment in time, often the last day of a month, fiscal quarter or year. It outlines three primary areas: the organization’s assets (such as cash, investments, property and equipment), liabilities (such as payroll, loans and other expenses) and net assets (the value of its assets minus its liabilities, which would be called owner’s equity on a for-profit balance sheet).

Balance sheets serve several basic nonprofit accounting purposes. In addition to providing important information about a nonprofit’s financial stability, a nonprofit balance sheet can, for example, be analyzed to reveal insights about a nonprofit organization’s liquidity and working capital. Nonprofit balance sheets also aid in the auditing process. While the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) doesn’t audit nonprofits, federal and state agencies can, depending on a nonprofit’s size and spending. In particular, large nonprofits’ financial statements often are independently audited to enhance their credibility to donors and other stakeholders. Lastly, nonprofits use their balance sheets for tax filing purposes and to apply for tax-exempt status.

Key Takeaways

- A nonprofit balance sheet, also known as a statement of financial position, provides stakeholders, such as members, donors, volunteers and board members, with insights into the financial health of the organization.

- Balance sheets for nonprofits are like those from profit-driven companies but differ largely in how they categorize and record net assets (called equity on for-profit balance sheets).

- Nonprofits categorize and record assets differently, primarily because the revenue they receive from grants, donations and fundraising often comes with restrictions.

- Analyzing a nonprofit balance sheet can add to your understanding of the organization’s working capital position, its reliance on debt for funding operations, the existence of any restrictions on assets and asset-growth patterns developed over several years.

Nonprofit Balance Sheet Explained

There are two types of accounting approaches nonprofits can use when building their balance sheets: cash or accrual. They mainly differ in the timing of how they recognize revenue and expenses.

Cash-basis accounting recognizes revenue and expenses at the time monies are received or paid. It’s a simple, easy-to-use method often selected by smaller organizations. One drawback of the cash-basis approach, however, is that it can sometimes paint an inaccurate picture of a nonprofit’s financial health. For example, a nonprofit may have a large amount of cash on hand, signaling a healthy financial position. But the company may have expenses expected to exceed its cash level that won’t hit the books for two months. The cash-basis method wouldn’t reflect the looming cash crunch.

The accrual method recognizes revenue at the time it is earned — at the time a donor pledges money, to cite a nonprofit-specific example — and expenses at the time they are incurred. In both cases, this may or may not be when funds are exchanged. Accrual-basis accounting is considered a more accurate way to depict any organization’s current financial situation because it matches revenue and expenses to when they’re earned or incurred within the same fiscal period.

For example, a nonprofit might receive a grant in March whose funds are restricted until the completion of a project in August. The accrual method recognizes the grant revenue in August (assuming the milestone is achieved), while the cash-basis method would record it in March when the cash is received. As a result, a cash-basis balance sheet wouldn’t reflect the nonprofit’s obligation to complete the project in the future and would appear cash-rich in March. A disadvantage of the accrual method is that it can create cash flow management problems if the organization doesn’t separately — and rigorously — manage its cash flow. For example, under accrual accounting, the nonprofit would record the restricted grant under discussion here as an asset in March, regardless of whether the cash is in hand. In such a case, a close reading of the accrual-basis balance sheet would reveal the nonprofit’s true liquidity, because the grant asset, incorporated into the cash or accounts receivable account, would be offset by a deferred revenue liability (reflecting the obligations of the restricted grant). These accounts are illustrated in the accompanying sample nonprofit balance sheet, above. As the obligations are satisfied, the deferred revenue is reduced on the balance sheet and the grant revenue is recorded on the statement of activities (the nonprofit equivalent of the for-profit income statement).

It’s important to remember that the balance sheet is just one part of the overall financial picture for nonprofit organizations. To fully understand a nonprofit’s financial health, it’s critical to view the balance sheet in combination with other core financial statements, including the statement of activities, which details a nonprofit’s revenue and spending on various programs and activities (the equivalent of a profit-and-loss or income statement in a for-profit organization); the statement of cash flows, which provides critical details about the timing and sources of cash moving in and out of the organization over a specific period; and the statement of functional expenses, which segments expenses into three broad categories (programs, management and general, and fundraising) and provides specific details on each expense.

Balance Sheet vs. Statement of Financial Position

A for-profit balance sheet and a nonprofit statement of financial position are mostly the same, although they differ in how they categorize assets and record them. Both contain three primary components — taught in any accounting 101 course — though their nomenclature can differ.

Assets

Broadly speaking, an asset is a tangible or intangible item of value that a company owns or is owed. Tangible assets can be seen and touched, such as property and buildings, while intangible assets, such as patents, cannot. Nonprofits categorize assets in the following three ways, depending on whether they’re tangible or intangible, as well as the amount of time it would take to convert them to cash, known as liquidity:

- Current assets: Current assets can be converted to cash relatively quickly, defined as within a year. This includes cash but also accounts for short-term investments (such as securities), accounts receivable and contributions receivable (such as pledges from donors and grants). It also includes prepaid expenses, such as insurance or software subscriptions. As part of their mission, some nonprofits might also carry inventory as a current asset, for example, to sell or offer in return for donations. Current assets are reported on the balance sheet at their current value.

- Fixed assets: Fixed assets are tangible items that are considered “noncurrent,” meaning that the nonprofit would expect them to have a useful life greater than one year. These include property, such as land and buildings; equipment, such as computers, furniture and fixtures; and any improvements made to leased property. Nonprofits record fixed assets as capital expenses at the time of purchase and record the asset’s depreciation over time.

- Other long-term (or noncurrent) assets: These are assets that don’t fit the definition of a current or fixed asset. They include intangible assets, such as intellectual property and patents, which can be amortized over time, as well as long-term investments in securities that are expected to be held for longer than one year. It also includes goodwill, which occurs when one company acquires another and refers to the amount paid above the acquired company’s book value. Goodwill can be attributed to the intangible value of the acquired company’s brand name, customer base and reputation.

Liabilities

Liabilities are the opposite of assets, representing what an organization owes to another entity. A nonprofit balance sheet categorizes liabilities in the following two ways, based on when the expense is due:

- Current liabilitiesare short-term debts that companies expect to pay within a year. Examples include accounts payable, accrued expenses (such as salaries and rent) and short-term loans or portions of long-term loans due within a year. It also includes revenue that a nonprofit has yet to receive but expects to receive in the next 12 months. For example, if a grant is awarded but is expected to be paid in the next year, it’s treated like a short-term loan until paid, in the event the nonprofit is unable to use the grant for some reason. The same is true for deferred or unearned revenue, which refers to funds a nonprofit receives for goods or services expected to be delivered in the next 12 months, such as membership fees over the course of a year.

- Long-term liabilities are obligations due in more than a year. They can include portions of mortgages or other financing, such as leases, pensions, deferred compensation and accrued expenses. They also include deferred revenue for goods and services expected to be delivered in more than a year.

Net Assets

If a nonprofit company sold all of its assets today and paid all of its liabilities, the remaining monies would be its net assets. In the for-profit world, that remainder is called equity, which gets distributed among owners/shareholders. Why the difference in terminology? Nonprofits have no owners or stakeholders, so they have no equity or distributed profits. These differences ultimately reflect the different missions for nonprofit and for-profit companies. The goal of for-profit companies is exactly that: more profits. Nonprofits, on the other hand, need to generate revenue but only as a means to an end: to support a mission. Despite these differences, some nonprofits have profited — metaphorically speaking only, of course — by applying for-profit accounting principles to their nonprofit missions.

Nonprofits categorize net assets in a unique way, known as fund accounting, that reflects rules around how funds (usually in the form of donations, grants and fundraising) are received. It also provides transparency about how the funds will be used to fulfill the mission. Nonprofits traditionally categorized net assets in one of three ways, but, beginning in 2018, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) consolidated and renamed net asset classifications for nonprofits as follows:

- Net assets without donor restrictions (formerly “unrestricted net assets”): With FASB’s changes, unrestricted net assets were renamed “net assets without donor restrictions” — but the definition remained the same. Nonprofits can use these assets as they see fit. For example, membership dues and museum admission fees typically have no restrictions, meaning that nonprofits can use them to pay salaries, rent or any other organizational expenses.

- Assets with donor restrictions (formerly “permanently restricted net assets” and “temporarily restricted net assets”): Permanently and temporarily restricted net assets were combined by FASB’s 2018 action into the single category of assets with donor restrictions, which can be used only according to limitations placed by the donor. An endowment fund for a scholarship is an example of a permanently restricted asset. The fund is set up to generate income that can be used only for the scholarship, and, usually, the principal amount is permanently restricted and can never be spent. Temporarily restricted assets come with initial limitations that can be lifted pending certain circumstances, usually related to periods of time or meeting specific conditions. This might include a grant for an explicit achievement that isn’t payable until the achievement is accomplished.

In the event that restricted funds can’t be used for the required purpose or during the specified period of time, the nonprofit must seek permission from the donor to use them for another purpose, petition a court to modify the restrictions or return them to the donor.

How to Read a Nonprofit Balance Sheet

A nonprofit balance sheet should tell board members, donors, auditors and other stakeholders whether the organization has the resources necessary to fund operations in the short and long terms. To probe that question, it’s important to know what to look for when reading a nonprofit balance sheet. Any balance sheet analysis should start with understanding the following three key themes that can be learned from the data:

- Trends: A balance sheet reflects a moment in time and doesn’t necessarily give a complete view of nonprofit financial health. Most balance sheets compare current results to those of the most recent prior period but, to better understand trends, be sure to review multiple previous balance sheets. Have net assets steadily trended upward in recent years? Does an influx of restricted assets limit available funds for day-to-day expenses?

- Liquidity: In general, a nonprofit balance sheet should demonstrate that the organization has more current assets than current liabilities — meaning, can its liquid assets cover its short-term obligations, such as rent, salaries or any other immediate expenses? Liquidity also factors into long-term planning for nonprofits. Balance sheets should also show unrestricted net assets that can be converted to cash to respond to changes in market conditions, such as an economic downturn or an unexpected acquisition opportunity.

- Debt: Most nonprofits have some form of financing from banks or other financial institutions. They may also issue bonds to raise funds. When debts outweigh assets, however, a nonprofit could find itself unable to meet its payment obligations. This could impact the nonprofit’s credit, making it more difficult to secure future financing, or it could lead to a financial crisis. Lower debt, on the other hand, reflects greater financial flexibility and stability.

Power Your Nonprofit With Accounting Software

With the power to automate time-consuming tasks like creating journal entries, calculating payroll taxes and generating compliant financial reports, accounting software gets your head out of the books and back to what matters: fulfilling your organization’s mission.

Take the free NetSuite product tour today (opens in a new tab)

Interpreting the Financial Health of Nonprofits

The next step in reading a balance sheet is to use the information it presents to calculate the financial metrics and key performance indicators (KPIs) that are most helpful in clearly interpreting a picture of the nonprofit organization’s short- and long-term financial health. Among these are months of cash on hand, the current ratio, months of liquid unrestricted net assets (LUNA) and leverage ratio.

Months of cash on hand: The formula for months of cash on hand measures liquidity by dividing current assets by the organization’s average monthly expenses. The result reveals how long a nonprofit can pay its bills without need for any additional income. For example, if a company has $100,000 in current assets, with monthly expenses of $20,000, it has five months of cash on hand to support operations. Three to six months of cash on hand is normal for nonprofits. The greater the number of months, the healthier the organization’s short-term outlook.

Current ratio: This KPI takes a slightly longer term look at liquidity by dividing current assets by current liabilities, reflecting a nonprofit’s ability to meet its obligations over the ensuing 12 months. For example, if a nonprofit lists current assets of $100,000 and current liabilities of $90,000 on its balance sheet, its current ratio is 1.11. The higher the ratio, the better — up to a point. A too-high ratio may indicate the organization has excess money that could be invested or otherwise put to use. Ratios below 1.0, however, indicate potential difficulty meeting expenses over the next 12 months.

Months of LUNA: Because nonprofits often have funds tied up in restricted assets they can’t always easily access, months of LUNA — that is, liquid unrestricted net assets — looks at how many months of freely available funds a nonprofit has available to cover expenses. Monthly LUNA is calculated by subtracting the value of the assets a nonprofit owns but can’t liquidate quickly (property and equipment) from its unrestricted funds, then dividing that number by average monthly expenses. The formula looks like this:

Months of LUNA = (Unrestricted net assets - equity in property and equipment) / Average Monthly Expenses

For example, say a nonprofit has $200,000 in unrestricted assets. It also owns its building and equipment, worth $225,000, but still owes $75,000 in loans for them. The nonprofit averages $10,000 in monthly expenses. Months of LUNA would, therefore, be five: $200,000 (property and equipment value) – $150,000 (the outstanding loan) ÷ $10,000 (monthly expenses) = 5 months of LUNA. Nonprofits should strive for at least three months of LUNA.

Leverage ratio: Ideally, stakeholders prefer that nonprofits limit long-term reliance on debt in order to fund operations; the leverage ratio KPI helps with that evaluation. To calculate leverage ratio, divide total liabilities by total assets. For example, if a nonprofit lists $15,000 in total liabilities on its balance sheet and has $100,000 in total assets, its leverage ratio would be 15%. A leverage ratio of 10% or less indicates that the organization doesn’t require much in the way of loans or bonds to maintain operations, reflecting a strong financial position and future flexibility. Increases in leverage ratio over time, however, could warrant concern that the organization will struggle to meet its future debt obligations.

Common Mistakes in Interpreting Nonprofit Balance Sheets

Reading nonprofit balance sheets poses particular challenges because of the unique accounting rules nonprofit organizations must follow. For example, someone unfamiliar with nonprofit accounting rules may misinterpret the actual amount of funds available to the organization, due to the presence of restricted funds. This can lead to inaccurate assumptions about financial performance that lead to misinformed planning decisions.

Avoid the following three common mistakes to get a more accurate assessment of a nonprofit’s balance sheet

Focusing Only on One Section

A balance sheet is a puzzle. Looking at only one piece obscures the big picture. For example, a nonprofit could show strong growth in current assets in a given year, with sharp increases in fundraising and grants. This might give the impression that the organization is financially strong — if you overlook the liabilities section. Zeroing in on liabilities could indicate that the nonprofit’s debt increased substantially during the same period because of expenses related to remodeling its headquarters. The resulting squeeze in net assets could put the organization in a weaker long-term financial position.

Not Understanding Context

Sometimes a “bad” number in a nonprofit balance sheet isn’t necessarily bad, as long as the reader understands the context. For example, a typical balance sheet interpretation is that higher net assets (assets minus liabilities) is “good” and lower net assets is “bad.” But because a nonprofit’s goal is to put donations to work fulfilling its mission, the accumulation of too much “surplus” (a part of net assets) isn’t always a good thing. When it comes to increasing net assets, nonprofits must perform a balancing act: They should have enough unrestricted net assets to cover a period of operating expenses — say, six months — but it should not trend up over time to the extent that it makes donors think their money isn’t being used for its purpose, and/or it creates a potential noncompliance issue with tax authorities.

Not Considering Trends Over Time

One way to identify directional trends when assessing a nonprofit’s financial health is to look at more than one balance sheet. Ideally, looking at several years of balance sheets provides greater insight into whether a nonprofit’s financial outlook is improving or declining. For example, a current ratio lower than 1.0 suggests financial weakness. While a current ratio below 1.0 isn’t ideal, looking at balance sheets for the two prior years might indicate that the current ratio has been rising slowly but steadily, providing a reason for optimism.

Get Your Nonprofit Account Under Control With NetSuite

The nuances of nonprofit financial management require solutions that not only make financial reporting simple and accurate but also incorporate the specific requirements nonprofits need. NetSuite’s cloud-based accounting software offers a wide range of components to simplify accounting and reporting for nonprofits, including a comprehensive set of tools for nonprofit budgeting, forecasting and reporting. Why NetSuite for nonprofits? NetSuite Advanced Financials extends nonprofit-specific capabilities to revenue recognition, multicurrency support and financial planning and analysis. NetSuite Grant Management specifically helps nonprofits manage grants from application to closeout, including grant proposal management, award tracking and financial management. NetSuite SuiteTax helps nonprofits manage tax compliance, including sales and use tax, value-added tax (VAT) and Goods and Services Tax (GST). Finally, NetSuite SuiteAnalytics provides powerful analytics and reporting capabilities to drive greater insight into financial operations and power better informed decisions.

With the right background, a nonprofit balance sheet — aka the statement of financial position — need not be mysterious to interpret. It’s important to keep in mind, however, that balance sheets by any name are only one piece of the financial puzzle for nonprofit organizations. Reading a balance sheet provides critical, top-level financial information, but a nonprofit’s statement of activities, statement of functional expenses and cash flow statement must be evaluated together to see the full picture of the organization’s financial outlook.

Nonprofit Balance Sheet FAQs

What insights can be determined from your nonprofit balance sheet?

A nonprofit balance sheet provides important details about the organization’s financial health at a specific moment in time, usually the last day of a month, fiscal quarter or year. It lists details about the nonprofit’s total assets, liabilities and net assets, which is the difference between assets and liabilities. A nonprofit’s balance sheet provides members, donors, volunteers, board members, auditors and other interested parties with a high-level view of the organization’s ability to fund operations to support its mission.

Where to find a nonprofit’s balance sheet?

A nonprofit’s balance sheet can be found in several ways. For example, it’s included with the organization’s annual report and it’s also submitted annually to the Internal Revenue Service using Form 990.

When do nonprofits need the balance sheet?

Nonprofit balance sheets are required in several instances. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requires nonprofits to file financial information using Form 990 when they set up the organization and annually thereafter, with the balance sheet required as part of the form. Only very small nonprofits — those with $50,000 or less in annual revenue — are allowed to file a postcard-size form that doesn’t require balance sheet details. A balance sheet is also necessary whenever nonprofits apply for tax exemptions. Nonprofits also must supply balance sheets if and when state or federal agencies request audits for any reason. Finally, nonprofits need to provide balance sheets to members, donors, prospective donors and other stakeholders, usually as part of independently audited financial statements, to build support for their mission and to encourage continued investments. This is usually done annually.

How often should a nonprofit update its balance sheet?

Nonprofits should update balance sheets whenever they need to provide new financial information to stakeholders, but otherwise at least annually. Balance sheets should also be updated whenever nonprofits apply for tax exemptions. Finally, nonprofits should update their balance sheets whenever they provide reports to members, donors and prospective donors. Most nonprofits provide updated financial reports annually.

How to do a balance sheet for a nonprofit?

Nonprofit balance sheets detail the financial value of three key components of the organization: assets, liabilities and net assets. These are usually listed along the left side of the balance sheet and are segmented into groups, based on the type of asset or liability and its liquidity (current, noncurrent, tangible or intangible). The balance sheet also details whether net assets are unrestricted (free to be spent as the nonprofit wishes) or restricted (limited by donors in how they can be spent). Balance sheets often compare these values to a prior period, such as the previous year.

What are the four basic financial statements for a nonprofit?

The four main nonprofit financial statements start with the statement of financial position (the nonprofit equivalent of a balance sheet). The other three are the statement of activities (similar to an income statement), which details the organization’s revenue and its spending on various programs and activities; the statement of cash flows, which details the nonprofit’s sources of cash and how that money moves into and out of the organization; and the statement of functional expenses, which provides more detailed information on expenses.

Why does a nonprofit have to show financial statements?

The main reason nonprofit organizations should want to produce financial statements is that they are often crucial to building donor support and, in general, enhance a nonprofit’s credibility with all its stakeholders. But nonprofit financial statements are also necessary for multiple reasons. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requires nonprofit financial statements every year, whether or not the nonprofit is tax-exempt. The IRS also requests financial statements whenever nonprofits apply for tax-exempt status. Also, while the IRS doesn’t audit nonprofits, state and federal agencies can, at which time they’ll require financial statements.