Demand planning is the process of forecasting demand for a product or service and aligning inventory and other resources to meet that demand by analyzing past results, changing market conditions and expected sales. But you can’t plan for the future without the right information. That’s where demand planning key performance indicators (KPIs) can help.

Generally speaking, KPIs track how well a company is progressing toward its goals and inform decision-making. In the case of demand planning, keeping a close eye on KPIs can help improve ordering accuracy, uncover shifts in demand and monitor sales. And make no mistake: Demand planning can have significant impacts on a company’s bottom line, as many businesses have learned — often the hard way.

What Is Demand Planning?

Demand planning helps a business predict future sales. It’s a supply chain management process that studies historical customer behavior, projected trends and market and economic conditions, among other factors, to increase the chances of meeting customer demands while avoiding excess inventory. While demand forecasting focuses on predicting future sales trends, demand planning uses demand forecasting’s insights to fulfill expected sales more efficiently. Demand planning touches on every aspect of a business, from sales and marketing to purchasing, supply chain operations, production and finance.

What Are Demand Planning KPIs?

Given how rapidly markets change and demand ebbs and flows, successful demand planning requires accurate, real-time information. Demand planning KPIs are designed to provide up-to-date intelligence about activities that are critical to planning. Some demand planning KPIs directly gauge the results of demand planning efforts, such as the mean absolute percentage error. Others provide insight about future demand, such as a Pareto analysis of customers (more on that later) and prebooking metrics. Some, such as the weekly item location forecast error, can even reveal how supply chains and sales predictions are affecting individual local outlets.

Why Are Demand Planning KPIs So Important?

Demand planning KPIs are important because they can provide insights that are critical to the bottom line. A KPI signaling that sales have underperformed in a particular market may trigger a flash sale or price drop to reduce inventory, for example. Or, a KPI that points to a strong upward trend for a product can mean a company needs to adjust its supply chain plan to increase production. The nature of these examples also serves to emphasize why it’s important that demand planning KPIs are updated in real time, so all key metrics are accurate, up to date and ready to be analyzed at any given moment.

Failing to closely monitor demand-planning KPIs can be costly. Some high-profile examples of demand planning snafus include Walgreens’ failure to recognize the trend of rising generic drug prices in its 2014 forecasts. The result: Those rising prices squeezed margins, resulting in a $1.1 billion drop in earnings and costing the CFO his job. In 2001, errors in Nike’s demand planning program caused the company to order $90 million worth of a poor-selling shoe. How did it affect the brand’s financial performance? It cost Nike an estimated $100 million in sales that year and cut its stock price by 20%.

How to Choose the Right Demand Planning KPIs

Improving the accuracy of your business’s demand planning is not a simple or easy task, as there is no one-size-fits-all indicator that will put a business on the right track. There are several essential KPIs most companies use to gauge demand planning (such as the first 10 examples below), but there are also a wide variety of demand-planning KPIs that may be particularly useful to one business but not another.

Determining which KPIs are best-suited to your company can involve some trial and error. Each metric has its own advantages and disadvantages, and every business has its own goals, whether it’s rapid growth or maintaining market share. Therefore, the “right” demand planning KPIs will vary from one company to another. Fortunately, there is a wide variety of KPIs to choose from.

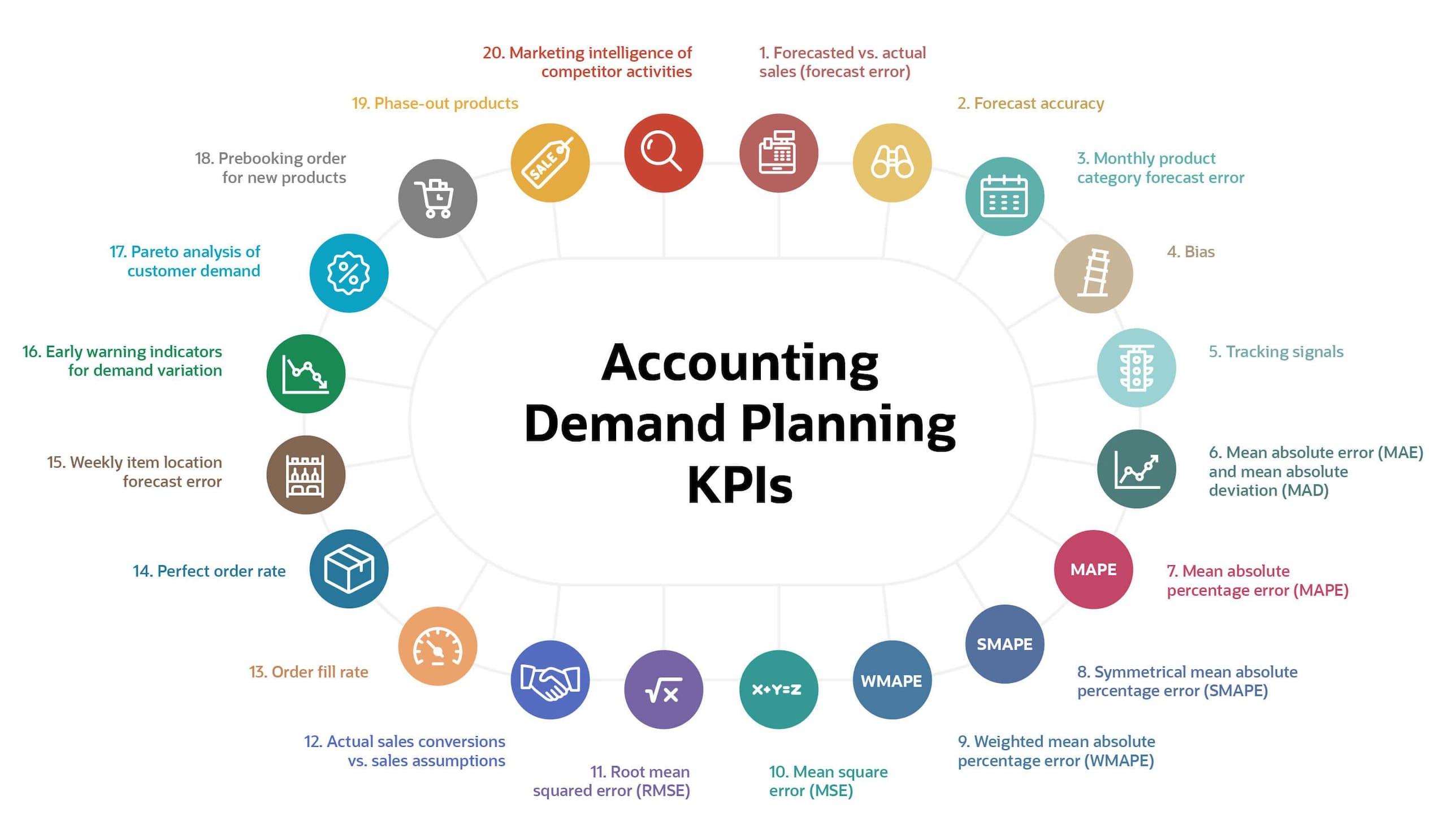

Top 20 Demand Planning KPIs and Metrics for Your Dashboard

Given the cross-functional nature of demand planning, which requires collaboration among disciplines such as sales forecasting, supply chain management and inventory management, information must come together as easily as possible. A demand planning dashboard can help by aggregating KPIs in an easy-to-comprehend visual interface that can be shared and customized across roles. The linchpin, of course, is to select the demand planning KPIs that are most important to your business.

There are demand planning KPIs for nearly every area of business. And many industries and individual companies have developed custom KPIs to give them insights into demand planning that address their particular challenges and characteristics. Nevertheless, some essential demand planning KPIs apply to any business, whether you sell shoes or develop pharmaceuticals.

Here are the top 20 demand planning KPIs — followed by explanations and how to calculate each one. Be warned: Some require real math, so it’s a good idea to keep a calculator at hand.

- Forecasted vs. actual sales (forecast error)

- Forecast accuracy

- Monthly product category forecast error

- Bias

- Tracking signals

- Mean absolute error (MAE) and mean absolute deviation (MAD)

- Mean absolute percentage error (MAPE)

- Symmetrical mean absolute percentage error (SMAPE)

- Weighted mean absolute percentage error (WMAPE)

- Mean square error (MSE)

- Root mean squared error (RMSE)

- Actual sales conversions vs. sales assumptions

- Order fill rate

- Perfect order rate

- Weekly item location forecast error

- Early warning indicators for demand variation

- Pareto analysis of customer demand

- Prebooking order for new products

- Phase-out products

- Marketing intelligence of competitor activities

1. Forecasted vs. Actual Sales (Forecast Error)

Measuring forecasted sales against actual sales numbers indicates whether the sales department or specific teams are on target to meet their goals. This simplest of KPIs is also known as “forecast error” and can be delivered weekly, monthly, quarterly, month-to-date and year-to-date — or all of the above — depending on the product or service and how quickly decisions need to be made. For demand planners, it’s the top-line insight into the quality of their output; just as often, it’s used by sales managers to check on sales performance and push the team, as needed. The formula is:

|

Forecasted vs. actual sales (forecast error) = Actual sales - Forecast sales |

For example, say a quarterly forecast for a consulting firm calls for its software division to bring in $5 million in revenue, but that group only brings in $4 million. The forecast error would be $1 million, the difference between those numbers.

2. Forecast Accuracy (FA)

Forecast accuracy is the big-picture demand planning KPI. This tells you how accurate your predictions for demand and sales have been. The better your FA, the more aligned your operational costs are with demand and the higher your profits. A good or acceptable number for this KPI will vary depending on the product and business scenario. For a new product with no sales history, a forecast accuracy of 80% is considered very good. (Seasonal products may be an exception to this rule if there are large variations due to weather, which can result in lower accuracy percentages.) However, products with a long sales history should target an FA of 90% or better. Like many KPIs, FA can be calculated as frequently as a company needs or is able to given the velocity of its particular business cycles. The formula is:

|

Forecast accuracy = 1 – [Absolute value of (Actual sales for time period – Forecast sales for same time period) / Actual sales for time period] |

So, if a company’s forecast called for it to sell 100 units of a particular product and it actually sold 115, its FA was 87%: 1 – [(115 – 100) / 115], or 1 – .13 = .87. Note that this formula disregards the positive or negative sign (that’s what “absolute value” means). For example, if the company sold 87 units against the same 100-unit forecast, it’s FA is 85%, not -85%.

3. Monthly Product Category Forecast Error (MPCFE)

This demand planning KPI is simply forecast accuracy (FA) applied to a specific product category on a monthly basis. With ramifications across several departments, this metric can help fine-tune changes in sales and marketing, as well as alert planners when supply chains need to be tightened up. In general, monthly product category forecast error should be more accurate than companywide forecasts since the information available to demand planners is more precise. The formula is:

|

Monthly product category forecast error = 1 – [Absolute value of (Actual product category sales for month – Forecast product category sales for month period) / Actual product category sales for month] |

4. Bias

Bias, also known as mean forecast error (MFE), is the tendency for forecast errors to trend in one direction — consistently higher or lower than actual sales results. It’s important to track bias so, if detected, it can be corrected before it skews forecasts for too long in one direction, which could cause excess inventory costs (if the bias is toward over-forecasting) or lost sales opportunities (if the bias is toward under-forecasting). Bias can come from many sources, such as managers’ desire for forecasts that match sales targets or departmental goals. The formula is:

|

Bias = Sum of observed forecast errors over multiple periods / Total number of observed periods |

For example, let’s say you want to calculate bias for four weeks in February where demand planners forecast sales of 10 items per week. As the chart below shows, sales in week one were 12, so the forecast error was 2; week 2 saw actual sales of 8, making for an error of -2; week 3, 8, for another -2; and week 4, 7, resulting in a -3. The sum of those four forecast errors is -5 (2 + -2 + -2 + -3), and -5 divided by four forecasting periods yields a bias of -1.25.

Bias for February |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Sum of forecast Errors |

|

| Actual sales | 12 | 8 | 8 | 7 | |

| Forecast | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| Forecast error | 2 | -2 | -2 | -3 | -5 |

| Bias = -5/4 = 1.25 | |||||

5. Tracking Signals (TS)

Tracking signals are another way to measure the existence of persistent bias. Analyzing tracking signals over a long period of time can also indicate the accuracy of the forecasting model. The formula is:

|

Tracking signal = (Actual sales for one month – Forecast sales for that month) / Absolute value of (Actual sales for one month – Forecast sales for that month) |

This formula is for one tracking signal in one observed period and results in either 1 or -1. A TS of 1 indicates under-forecasting (demand is higher than the forecast) and a TS of -1 indicates over-forecasting (demand is lower than the forecast). Demand planners typically calculate this KPI by summing the tracking signals for many periods. If tracked for 12 weeks, for example, the highest possible result is 12 and the lowest is -12. A TS of zero is always ideal, indicating no consistent bias.

6. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD)

Mean absolute error and mean absolute deviation are two names for the same formula, a popular one with demand planners. It’s a straightforward KPI that measures forecast accuracy by averaging the magnitudes of the forecast errors and thereby revealing the variability of forecasts over time. As the name implies, it is the average of the absolute error (also known as deviation), which means that the positive and negative values don’t cancel each other out (as they do, for example, in the bias calculation). It is expressed as a number of units rather than a percentage, so it is not scaled relative to the amount of demand. An MAE of five units is great if your demand is 1,000 but rather poor if demand is only 10. The formula is:

|

Mean absolute error (or deviation) = Sum of observed absolute forecast errors over multiple periods / Number of periods |

The accompanying chart calculates the MAE/MAD for February from the example described in KPI No. 4 (bias).

Mean Absolute Error for February |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Sum of Absolute Forecast Errors |

|

| Actual sales | 12 | 8 | 8 | 7 | |

| Forecast | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| Forecast error | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| MAE= 9/4 = 2.25 | |||||

7. Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)

Mean absolute percentage error is a statistical measure of a forecast’s accuracy. This demand planning KPI expresses the degree of error as a percentage, so it remains applicable regardless of demand magnitude and is easier to communicate to different departments — in other words, people who aren’t demand planners and/or statisticians. The formula is:

|

Mean absolute percentage error = Sum of (Forecast error for time period / Actual sales for that period) / Total number of forecast errors x 100 |

The accompanying chart calculates MAPE for February using the same forecast and sales numbers from No. 4.

Mean Absolute Percentage Error for February |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Sum of Errors % |

|

| Actual sales | 12 | 8 | 8 | 7 | |

| Forecast | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| Error % | 16.7 | 25 | 25 | 42.9 | 109.6 |

| MAPE= 109.6/4 = 27.4% | |||||

8. Symmetrical Mean Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE)

If there is little actual sales data, MAPE can often make forecasting errors seem worse than the actual trends. To compensate, demand planners also employ symmetrical mean absolute percentage error. The advantage of using this KPI to express forecasting errors is that it has both a lower (0%) and an upper (200%) limit in order to overcome some of the disadvantages of MAPE. The formula is:

|

Symmetrical mean absolute percentage error = 2 / Number of forecast errors x Sum of (Forecast sales for a time period – Actual sales for time period) / (Forecast sales for a time period + Actual sales for that time period) |

For those still following along, the accompanying chart calculates SMAPE for our ongoing example.

Symmetrical Mean Absolute Percentage Error for February |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Sum of Errors % |

|

| Forecast - Actual | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |

| Forecast + Actual | 22 | 18 | 18 | 17 | |

| 9.1% | 11.1% | 11.1% | 17.6% | 49.0% | |

| SMAPE = 2/4 * 49% = 24.5% | |||||

9. Weighted Mean Absolute Percentage Error (WMAPE)

Weighted mean absolute percentage error is another KPI used to express forecasting errors and is designed to be yet another improved version of MAPE. The WMAPE improves on MAPE by weighting it using actual observations or, in a typical case of sales forecasting, weighting it according to actual sales volumes. The formula is:

|

Weighted mean absolute percentage error = Sum of (Actual sales for a time period – Forecast sales for same period) / Actual sales for same period |

This chart calculates WMAPE for February.

Weighted Mean Absolute Percentage Error for February |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Sums | |

| Actual Sales | 12 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 35 |

| Forecast | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| Actual - Forecast | 2 | -2 | -2 | -3 | -5 |

| WMAPE = -5/35 = -14.3% | |||||

10. Mean Square Error (MSE)

Mean square error evaluates forecast performance by averaging the squares of the forecast errors, which removes all negative terms. It has the effect of giving more weight to the larger errors in the data and can therefore overemphasize those factors in the error rate it produces. MSE is not a percentage, and there’s no benchmark against which to judge results, but the lower the number, the more accurate the forecast. The formula is:

|

Mean square error = Sum of squares of forecast errors over multiple time periods / Number of time periods |

Once again using the numbers from our running example, this chart calculates the MSE for February.

Mean Square Error for February |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | |

| Actual Sales | 12 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Forecast | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Forecast Error | 2 | -2 | -2 | -3 |

| Squad Error | 4 | 4 | 4 | 9 |

| MSE = 21/4 = 5.25 | ||||

11. Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

Root mean squared error is simply the square root of the MSE. Strictly speaking, it is defined as the square root of the average squared error. It’s helpful in determining the degree of severity of forecasting errors, telling demand planners how seriously they may need to address the errors. However, as a KPI it should also be noted that like MAE, the RMSE is not scaled according to the actual demand. The formula is:

|

Root mean squared error = Square root (Squared (Forecast sales for a time period – Actual sales for the same time period)) |

In the running example, RMSE would be the √5.25 (the MSE value calculated for No. 10), which is 2.29.

12. Actual Sales Conversions vs. Sales Assumptions

With this KPI, demand planners track the results of marketing activities against expected results in order to adjust future production and inventory plans. Recording early sales projections and then comparing them to actual sales can also help improve marketing and merchandising activities. The idea is to track the actual sales conversion rate and compare it to the sales conversion rate stipulated in the marketing plan. The formula is:

|

Sales conversion rate = (Leads converted into sales / Qualified leads) x 100 |

13. Order Fill Rate

Order fill rate is mostly used as an inventory management KPI, but filling customer orders quickly can influence long-term demand by satisfying those customers and leading to repeat business and positive word-of-mouth. It shows how many customer orders a business can fill directly out of available inventory. The formula is:

|

Order fill rate = (Number of customer orders shipped / Number of customer orders filled) x 100 |

14. Perfect Order Rate (POR)

The POR KPI measures how many orders are shipped without incident — i.e., damaged goods, inaccurate orders and late shipments, among others. Naturally, every organization aims for the highest POR possible because it not only reflects well on the manufacturing and logistical aspects of a company, but a high POR should also translate into a high degree of customer satisfaction. In other words, a high POR should factor into increased or steady demand; a poor POR rate will likely induce a drop in demand. The formula is:

|

Perfect order rate = Orders completed without incident / Total orders placed |

15. Weekly Item Location Forecast Error

Businesses with many different retail locations or distribution warehouses will often need to plan for demand per-item for discrete time periods, like a month or a week. The most popular approach for this purpose is to apply MAPE (No. 7) to measure forecast accuracy for each item requiring a demand plan and apply it weekly at every location. Observed over time, weekly item location forecast error delivers critical information comparing the results of point-of-sale systems and regional distribution data. It can correct logistical mistakes, for example, when sales exceed forecasts and store shelves remain empty (or the reverse, which can lead to overstocking). So reducing the location errors can contribute to important cost savings.

16. Early Warning Indicators for Demand Variation

The idea here is for demand planners to monitor MAPE and/or forecast accuracy KPIs weekly at the product category or even item level and take immediate action whenever actual sales differ from the forecast by 15% in either direction. The goal is to trigger changes in inventory and supply chain plans that better align actuals with demand throughout the business’s supply chain.

17. Pareto Analysis of Customer Demand

Coined by Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto in 1896, the Pareto principle says that 80% of a given set of results are caused by 20% of known factors. In terms of customer demand, this means the behavior of the top 20% of customers affects 80% of sales. Therefore, Pareto analysis of customer demand is the practice of focusing one or more of the demand planning KPIs described in this article to analyze only the behavior of a business’s top 20% of customers. The theory is that identifying and responding to changes in demand among that 20% will produce the biggest benefit in overall sales and profitability.

18. Prebooking Orders for New Products

If a product is made available for preorder prior to general availability, closely monitoring the number of preorders and matching it against forecasted expectations can provide a kind of early warning. It can tell demand planners whether to ramp up — or down — a planned production run. That can take some of the unpredictability out of a new product launch. Businesses can more accurately forecast product and sales volumes via demand planning using this KPI, thus avoiding shortages or too much inventory.

19. Phase-out Products

This is like the inverse of a new-product launch: a product’s end-of-life. Accurately timing the pace of a product transition can just as directly affect a company’s financial performance. So the demand for a product that is being phased out needs to be closely monitored using MAPE or FA weekly or even daily, depending on the product and situation. This helps a business continuously match supply with demand, maintain prices and prevent overstock.

20. Marketing Intelligence of Competitor Activities

In many cases, competitive analysis can help a company more accurately determine demand. While much of the necessary information isn’t publicly available, it’s worth the effort to try to determine the following three important KPIs:

- Competitor’s new product launch performance (based on unit sales and revenue).

- Competitor’s sustained stockout (gauges their shipping and delivery delays).

- Competitor’s quality issues or product recalls (based on customer reviews).

Such KPIs are a reminder that demand planners also need to keep an eye on the external business environment and related data.

Long-Term Capacity Requirement Forecasting Accuracy

Demand planners are also called on to contribute to a company’s long-term capacity planning to help ensure there will be sufficient production resources — such as factories, people and equipment — to meet the business’s production needs for years to come. Such long-term demand planning is critical to budgeting, capital expenditure planning, contract planning and the distribution system. However, it’s essentially a different discipline from day-to-day demand forecasting and planning, factoring in the long-term evolution of multiple product lines in the context of an ever-changing economy.

Visualizing KPIs With a Demand Planning Dashboard

Without effective visual presentation, it would be difficult for most people to make sense of all these demand planning KPIs. But when demand planning KPIs are graphically displayed on a dashboard, the most important information becomes quickly and easily accessible. Dashboards can automatically compare KPIs in tables, charts and other graphics, dispensing with manual processes so demand planners can focus on analyzing data and collaborating with their counterparts in other business departments.

Monitoring KPIs in a dashboard can help companies and demand planners assess progress toward their goals and tell them whether prompt action or more strategic changes are necessary, all in real time. A dashboard also makes it easier to convey results to a variety of departments and stakeholders that don’t have deep knowledge of demand planning metrics.

Tracking Demand Planning KPIs With Software

Demand planning KPIs require pulling together information from across a business, including sales, marketing, inventory, production and logistics. So the ability to link and coordinate business data in a single system is critical to accurate demand planning. A business needs to be able to aggregate such information to accurately plan its material purchases, calculate inventory, schedule employees and get work centers up and running to make on-time deliveries. It’s also critical that the data entry itself is automated in order to track KPIs in real time.

For these purposes, a demand planning tool tied to cloud-based enterprise resource planning (ERP) solution is best, such as NetSuite’s demand planning module. The module can combine demand planning KPI data and automate statistical analyses to help demand planners calculate optimal production and inventory levels faster and more accurately than humans could via pen and paper or spreadsheet. All this information is tied back to a central database that holds other critical, related data with the NetSuite ERP platform.

Demand planning is critical to any business’s sales and bottom line. But it has ramifications for nearly every part of the company, from purchasing to supply chain to marketing. A sudden, unanticipated demand can stymie suppliers, for example, or overtax shipping systems. And a drop in demand can leave a company with dead stock and high inventory costs. So it’s no surprise that demand planning encompasses a wide variety of information and requires continually updated data points. Monitoring the right demand planning KPIs is a difference-making proposition for any product business.

Demand Planning KPIs FAQs

What are the 5 key performance indicators?

There are many key performance indicators that monitor demand planning success. For most businesses, five main KPIs are:

- Forecast accuracy: The more accurate your forecast, the more efficiently you can run the business — and therefore, the higher your profits.

- Forecasted vs. actual sales: An indication of actual performance compared to what the organization expected.

- Mean absolute error (MAE): The average forecasting accuracy rate.

- Bias: The tendency for forecast errors to trend consistently in the same direction.

- Perfect order rate (POR): The measure of how many orders a company ships without incident.

What is KPI planning?

KPI planning refers to decisions that are made based on the metrics used in KPIs. The choice of KPIs depends on business goals, such as increasing sales or reducing production costs. Typically, KPI planning also involves sharing these metrics with the whole organization.

What are the KPIs for supply chain?

Since supply chains cover all the steps from building products to placing them in customers’ hands, perfect order rate (POR) — a measure of how many orders a company ships to customers without any problems — may be the ultimate supply chain KPI. Other important supply chain KPIs include on-time delivery, inventory-to-sales ratio, inventory carrying rate and weekly item location forecast error.

What is a KPI in procurement?

Procurement is the process of buying supplies a company needs to manufacture or resell as part of its business model. Some of the more noteworthy examples of procurement KPIs include compliance rates, supplier defect rates, rate of emergency purchases and supplier lead times.

How do you measure demand forecast accuracy?

Forecast accuracy (FA) compares predicted sales for a period to actual sales for the same period. The resulting percentage indicates the accuracy of the forecast. The formula to calculate FA is 1 – [Absolute value of (Actual sales for time period – Forecast sales for same time period) / Actual sales for time period].

What does demand planning mean?

Demand planning optimizes a business’s ability to meet customer demand in the most efficient way possible. It involves sales forecasting, supply chain management, production management and inventory management to balance supply with demand.

What is the difference between supply planning and demand planning?

Both are intimately related. Demand planning involves predicting customer demand for a business’s offerings. Supply planning involves managing inventory and supply chains to meet those predicted demands. Supply and demand planning work in concert.

What are the key components of a demand forecast strategy?

Demand forecasting is part of the larger demand planning process and forms the foundation of the planning process for anticipated sales. As such, the key components of a successful forecasting strategy may encompass data from several different internal departments, including past sales data and historical information about related seasonal costs. What components are included will depend on the demand planning goals. Those goals may include not just increasing sales, but also minimizing excess inventory or supply chain disruptions.