You've heard the adages.

These are variations on the 80/20 rule, or Pareto Principle, which states that 80% of outcomes or results come from 20% of causes or inputs — and thus, smart companies will seek to identify that 20% and do more of what's working. It takes a significant amount of effort to recruit, onboard and train new hires, for example. If the business can identify the minority of employees producing the highest output, it can avoid losing them to competitors by offering rewards and internal promotions. And, it can try to understand why these top-performing employees succeed and then apply those lessons towards retraining the existing workforce or screening future hires.

What Is the Pareto Principle?

In a nutshell, the Pareto Principle or 80/20 rule states that 80% of outcomes are a result of 20% of causes. For example, 80% of sales come from 20% of clients, 80% of profits come from 20 of products, or 80% of worker output comes from 20% of employees. The Pareto Principle was coined by a Romanian-American management consultant named Joseph M. Juran, who based his research on the work of the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto. During Pareto's research at the University of Lausanne in 1896, the economist discovered something that struck him: 80% of Italy's land was owned by 20% of the population. Continuing his research, Pareto discovered the same distribution in other countries — 80% of the land owned by 20% of the people.

Observations of the Pareto Principle in practice have continued well into the contemporary era as an index of everything from global inequality to a sales leader observing that 80% of closed deals are from 20% of salespeople. In business and decision-making contexts, it conceptualizes the imbalances frequently found in the relationship between inputs and outputs.

Key Takeaways

- The Pareto Principle can help companies identify opportunities to improve resource allocation.

- Businesses can take advantage of the Pareto Principle to increase revenues and lower costs.

- But take care to ensure what you're seeing isn't a false correlation or an outlier.

Pareto Principle Explained

The upshot of the 80/20 rule is that not all employees, products or customers deliver equal value. The critical few have a disproportionate effect, so it's important to identify high performers, determine what makes them effective and look to replicate those factors. Maybe the top 20% of customers generate 80% of profits. What commonalities can you find among those clients? How can you find more, similar, prospects? And just as important, how can you make very sure to keep those customers and increase loyalty?

There's a flip side — sometimes that 80% is a negative effect. Say a small manufacturer performs a COGS analysis and finds that 20% of raw materials drive 80% of its product costs. By finding lower-cost suppliers or alternative materials, it may be able to lower prices without diminishing the quality of its product.

How Does the Pareto Principle Work?

For a business to translate the Pareto Principle to action, find relevant correlations and use them to their benefit, analysts need to understand why these correlations tend to accumulate in the way they do.

First, let's start by throwing out the idea that the 80/20 split strictly defines the Pareto Principle. Scenarios falling under this rule can include 70/30, 60/40 or 90/10 splits. The exact ratio between causes and results isn't what's important. It's the fact that a minority of causes produces the majority of results. So instead of looking for an exact 80/20 split, watching for any uneven distributions can reveal Pareto effects within a business's employee or customer base or processes.

Second, there may be situations where the numbers don't add nicely up to 100. For example, imagine a company with 15 office locations, but only five are above 75% capacity; 10 are almost completely empty as most employees assigned to those sites continue to work from home. Therefore, almost 100% of the costs of maintaining physical office space goes to service 30% of locations.

Point is, if the business looks only for 80/20 distributions, it's likely to miss important insights.

At its heart, the Pareto Principle is a lesson about how distribution works in complex systems. Most inputs don't contribute equally to outputs — not every employee on a team consistently puts in the same effort, and not all customers contribute the same amount of value. Putting in one unit of effort sometimes won't equate to one unit of reward. Businesses can increase revenues, decrease costs and avoid diminishing returns by identifying situations where correlations are significantly skewed towards a small number of inputs.

Why Is the Pareto Principle Important for Businesses?

Winning a single new B2B customer can cost a significant amount of money — advertising, marketing salaries, the sales team's time. When a company identifies that 20% of customers generate 80% of profits, it suddenly has valuable, actionable insights.

First, it can work to minimize churn among that group. Proven tactics to head off customer attrition include closely tracking recency and value of last purchase metrics for VIP clients and setting threshold alerts that are automatically escalated to a customer service specialist, who is empowered to reach out with, for example, a special offer for "our most valued customers."

By rewarding these customers' loyalty, you not only hang on to them, you may be able to upsell additional products and services, increasing their value even more.

Second, you can study these customers, build a profile and more narrowly target sales efforts.

Any time the business recognizes an 80/20 correlation, it can benefit by applying time, effort and energy studying the 20% of causative factors, also known as "the vital few." Because these factors are already producing more output than their brethren, increasing their output even a little bit more may have outsize positive effects. Meanwhile, efforts to increase the yield of the underperforming 80% of factors might be met with minimal success.

Advantages of the Pareto Principle

Identifying the Pareto Principle at work in a business is more than just an effective way to increase revenues. It can also help businesses break through bottlenecks and identify structural problems. By understanding the Pareto Principle, a business can improve its products and services, resulting in lower costs and less customer churn.

Here are additional advantages of the Pareto Principle in a business context:

Double down on success:

The Pareto Principle tells companies they should do more of what's working. Suppose a business has a family of products, and 20% of those products generate 80% of revenue. Or, 20% of sales professionals deliver 80% of new logos. That's where to concentrate attention and efforts.

Rescue underperforming brands:

When using a Pareto analysis, businesses can understand why a department or product isn't gaining the expected traction.

Improve product quality:

Management consultant Joseph Juran was the first to apply the Pareto Principle in a business context. A quality control expert, Juran discovered that 80% of finished goods' defects were related to 20% of assembly line processes. By modifying these processes, his business was able to increase its overall product quality.

Improve resource allocation:

Businesses have a finite amount of time and money, and the natural impulse is to allocate resources equally to each customer, product and process. The Pareto Principle is a concrete way to understand why this instinct is wrong. If anything, businesses should identify underperforming factors — "the trivial many," as Juran would have put it — and either improve or eliminate them.

Disadvantages of the Pareto Principle

A potential problem with the Pareto Principle — or at least, with business adoption of it — is that it can applied to a false correlation or lead decision-makers to discount ameliorating factors. For example, a supplier may have dramatically raised prices, and that's contributing to a high COGS, with that one material representing an outsize percentage of product cost. However, it's possible that any other supplier would be as or more expensive, or that the spike is temporary.

Don't be too quick to eliminate the trivial many:

If a business discovers 80% of its products generate only 20% of profits, a reflexive instinct might be eliminating some percentage of that underperforming 80%. That is probably a bad idea. Best-case scenario, the business has eliminated 20% of its profits without a clear plan to recover them. Worst-case scenario: Some percentage of that 80% of products acted as loss leaders, attracting customers who would buy the more profitable 20% of goods.

Don't force correlations that may not exist:

The Pareto Principle is an observation, not a law. Say you identify an apparent mismatch in employee output between different retail locations and are considering options. Store A sells $300 in merchandise per worker per day while Store B barely makes $100. The first instinct might be to replace the workers. But what if the problem isn't the employees but a poor manager, theft or that Store B's neighborhood is changing and no longer wants your products?

Deciding when to act on a suspected correlation requires its own analysis. Is the value of taking an action high and the risk of acting, even if the hypothesis is wrong, low? If so, a move might make sense, just to see what happens. But if you lack certainty that outcomes and inputs are linked and an action comes with significant potential downside, do further analysis.

Consider the sample size:

How many customers, products or processes will the business consider when it looks for correlations? If you discover 40% of products produce 60% of profits, this might be an actual example of the Pareto Principle — but if the business produces only ten product lines, the evidence for correlation is a lot weaker.

Watch for outliers:

Instead of misidentifying a weak correlation as an example of the Pareto Principle, it's also possible to misidentify a strong correlation. For example, let's say a business finds that one customer — not one percent of its customers, but a single customer — is responsible for 20% of its revenue. That isn't an example of the Pareto Principle, even though a small cause is responsible for a significant effect. Instead, it's an outlier, a variation far above the mean. Although the outlier is worth studying, it may not be a scenario the company can replicate to its advantage.

Real-World Pareto Principle Examples

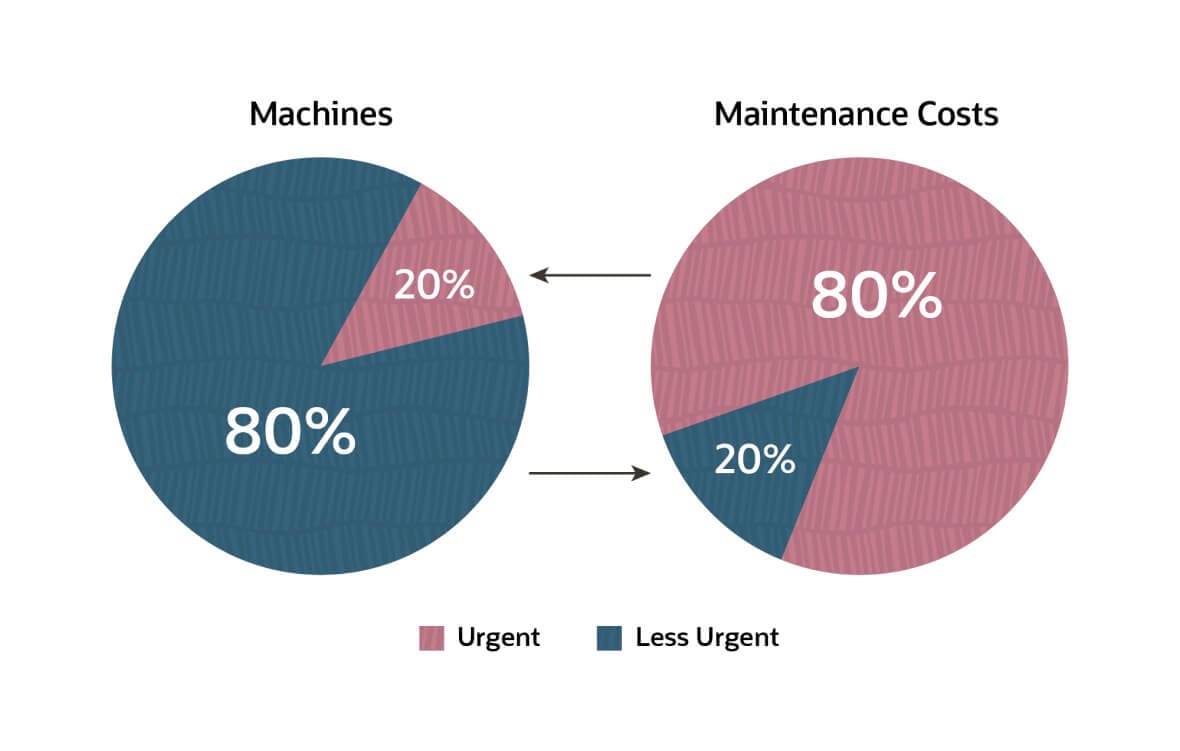

Consider a factory floor with high maintenance costs. After some analysis, the foreman finds that just 10% of equipment is responsible for 90% of unplanned downtime. But these are highly specialized machines that can't easily be replaced. The manufacturer can still increase productivity by adopting a preventive maintenance schedule, which is much less expensive than fixing problems after they occur.

Alternatively, let's think about a supply chain manager for a pharmaceutical company. Quality control is hugely important, and the goal is to help the company minimize drug recalls. The supply chain manager performs a Pareto analysis on vendors and finds that 60% of nonconformance issues come from 10% of suppliers. These suppliers can't be replaced right away, but their materials can and should be subjected to an enhanced inspection schedule, leading to fewer recalls and less bad press.

Application of the Pareto Principle in Inventory Management

The Pareto Principle can be an effective tool when applied to inventory management.

Product inputs and outputs are not evenly distributed — items have varying turnover rates, raw materials are cheap or expensive, pallets are heavy or light. That means cause and effect in a warehouse environment can align with Pareto Principles, and warehouse managers can take advantage of this using inventory analytics.

Following an inventory audit, a warehouse manager might find that 20% of raw materials are responsible for 80% of storage costs. That should drive a critical look at these items. Could they be more of a just-in-time purchase, or could they be stored more efficiently?

Or, analysis reveals that 20% of products represent 80% of handling time. That 20% might represent large and unwieldy items that must be handled via forklift. Again, if the company can't phase these products out, it may be able to find ways to cut handling times by placing them so forklift routes don't interfere with other workers or adding automation so that fewer humans are involved in transport.

Using the Pareto Principle, warehouse managers can lower costs, increase revenues, improve efficiency and reduce damage to products during storage and handling. With modern inventory management systems, it's easier to identify these opportunities.

Pareto Principle FAQs

What is the Pareto Principle?

The Pareto Principle is a standard distribution in which 80% of results flow from 20% of causes or efforts. One example is discovering that 80% of a company's revenue comes from 20% of customers.

What does the Pareto Principle mean?

The Pareto Principle is named after Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto who, in 1896, noted that 80% of Italy's land was owned by just 20% of the population. Pareto went on to discover this same ratio in other countries. His work was applied to business by management consultant Joseph M. Juran in the 1940s.

What is the 80/20 rule in life?

Day-to-day life holds many examples of the 80/20 rule, also known as the Pareto Principle. People might find that 80% of their budget spent on 20% of needs, like food and rent, or that 20% of exercise types burn 80% of calories. Looking for places where the Pareto Principle applies can help save time, effort and money.

Is the Pareto Principle true?

Short answer: yes. Long answer: The Pareto Principle is often observed in real life, but it's not a mathematical law. Although 80% of results often descend from 20% of causes, this isn't an exact ratio. There are times, for example, where 100% of results might result from 20% of inputs. That broadens the opportunity to find examples of the Pareto Principle in your daily life.