Supply chains are complex — a fact of life and a source of operational headaches for most businesses. Supply chain managers who have been around the block know these two things: They need to manage the complexity that is necessary in any system with so many moving parts, and, as importantly, they must do their best to stave off and stamp out all unnecessary complexity in their supply chains. This article breaks down the drivers, types and makeup of supply chain complexity and shares experts’ advice on how to manage it.

What Is Supply Chain Complexity?

Supply chain complexity emerges from interconnections and dependencies among the flows and partners involved in the procurement, production and distribution of goods and services. And, unfortunately, as those interdependencies grow in complexity, the odds of a supply chain disruption grow with them. From component shortages and transportation bottlenecks to spikes in consumer demand, disruptions ripple across companies’ interconnected and interdependent global supply chains.

Supply chain disruptions can prevent companies from meeting performance goals, making a profit and growing their business by introducing costs, delays and other risks, such as regulatory noncompliance. What’s more, a lack of visibility across complex supply chains acts as an impediment to strategic and operational decision-making throughout a company.

Key Takeaways

- Supply chains are becoming more complex.

- Specific management techniques can address drivers of complexity that range from customer expectations to environmental considerations.

- Technological advancements can also help tame complexity, but not without careful integration.

Supply Chain Complexity Explained

Supply chain complexity can bedevil companies, whether they are selling products or services. While manufacturers and retailers need to source the raw materials, components or wholesale goods that go into their final products, services companies also have to maintain a pipeline of the technology, services and other resources that go into running their businesses.

Compounding the complexity of modern supply chains is the fact that they are always changing, as the following four complexity drivers illustrate:

- Structure: The basic drivers of complexity include the number and variety of suppliers and customers, and the nature of their interactions.

- Dynamics: Change is a constant within any supply chain structure, as customer requirements evolve, competitive threats emerge or disappear, and industry standards advance. And, at the same time, companies in a buyer’s supply chain might be striking strategic alliances among themselves, outsourcing to third parties, merging with other companies, adopting new technologies or expanding into new geographies.

- Internal factors: Changing business strategies and communication breakdowns within one’s own company can exert sudden pressures on supply chains.

- External factors: Complexity increases with economic, environmental and geopolitical volatility — often unpredictably.

What Causes Supply Chain Complexity?

Supply chain complexity is often a function of size. A small, local business may have a few core suppliers, a single production facility and direct distribution to customers. Midsize businesses may need to manage many different types of suppliers, regional distribution centers and wholesale and retail outlets. And the largest enterprises operate highly complex, global networks of suppliers, production facilities, distribution centers and channels to market.

In each case, there are typically “tiers” of suppliers. In a basic example, a Tier 1 supplier to a clothing company might be a garment maker, which buys from a fabric mill (Tier 2), which buys from cotton farmers (Tier 3). The clothing company’s costs, quality and available inventory rely on all three tiers, though it may only have a relationship with the garment maker.

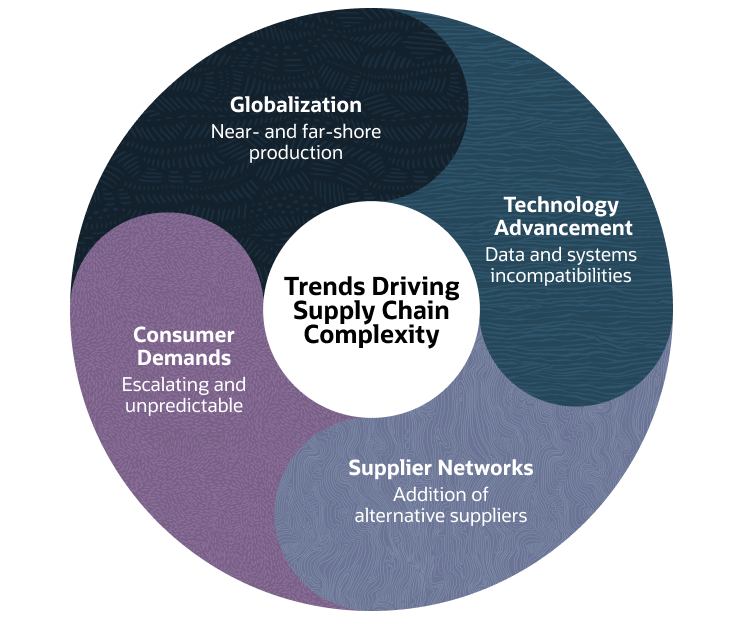

Beyond the basic size and structure of a supply chain, the top four drivers of complexity today revolve around globalization/localization, supplier network diversification, technology transformation and changing consumer demands.

Four Causes of Supply Chain Complexity

-

Globalization

Many U.S. companies extended their supply chains far from shore in the late 1900s and early 2000s, seeking to benefit from low-cost labor and other advantages. These globalized supply chains generated more complexity from complicated transportation routes, customs controls, currency fluctuations and weather patterns. But the issues involved in international logistics and manufacturing kept piling up, from trade wars and child labor to extreme weather and transportation bottlenecks, and reached a peak during the pandemic. In many cases, the cost/benefit equation didn’t add up anymore. The trend shifted to “near-shoring,” and, in 2023, for the first time in 20 years, the U.S. bought more goods from Mexico than China.

Still, global sourcing and distribution remain in the picture, especially since most of the world’s consumers live outside the United States. In a recent survey by Boston Consulting Group (BCG), 90% of North American executives said they had relocated some of their production or supply base out of China in the past five years. Of those, however, only half reported that they had shifted more than 20% of their related spending.

Such a redistribution can add complexity, especially if it involves setting up shop in entirely new countries. The BCG survey provided evidence of this fact, reporting that only about half of executives involved in redistributing their supply chain said they had met their objectives in terms of improving costs, shortening lead times or meeting sustainability goals. Each world region presents tradeoffs in these and other areas, the report concluded.

-

Supplier Networks

Supplier networks have grown in recent years, as alternative sourcing gained ground as a supply chain strategy for managing risk and increasing resilience. Abandoning single-source arrangements in favor of a broader set of suppliers clearly has its pros and cons — with added complexity headlining the downside list.

Single-sourcing has often meant fewer contracts to maintain, plus increased buying power based on high-volume orders. But it has also exposed companies to disruptions, if a supplier (or a supplier’s supplier) runs into trouble.

Alternative sourcing, however, is not an easy choice:

- Pros: As part of the near-shoring trend, which dictates locating production closer to the ultimate customer, the opportunity to set up new suppliers can mitigate some global transportation issues, such as high energy costs, extreme weather patterns and sporadic bottlenecks. Other benefits of alternative sourcing can include better pricing, due to competition among suppliers; more flexibility in meeting delivery schedules; and an ability to tap into more sources of product innovation.

- Cons: Potential downsides include the need to manage more supplier relationships and all that that entails in terms of transparency, quality control and other challenges. Worst case: Without careful communication and coordination, alternative sourcing could lead to supply chain fragmentation, in which numerous partners in many places operate as discrete links, rather than pulling together as part of the whole.

-

Consumer Demands

Consumer demand is never linear — or, at least, not for long. In just the past few years, for instance, an unprecedented surge in online shopping during the pandemic was followed by a drop-off a couple years later. Retailers everywhere veered from debilitating shortages to bloated inventories.

On an ongoing basis, fast fashion, extreme weather and consumer sentiments about spending stand out among the many causes of uncertainty affecting demand. Consumers also have increasingly specific requirements for how fast they want to receive products, as well as where they choose to order and pick up their purchases. Examples for online purchases include same-day or next-day delivery or in-store pickup. People also care more today about the environmental and social conditions under which their products are sourced, produced and shipped.

-

Technological Advancements

Technology is often a double-edged sword. Digital innovations can provide companies with greater visibility across their supply chains to achieve faster responses to potential disruptions. The Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain provide examples in which tiny radios can track items, distributed ledgers can transparently record their progress, and AI-fueled data analytics can detect when things aren’t going according to plan.

At the same time, silos and other integration issues often emerge among departments, subsidiaries, buyers and suppliers using different digital tools and systems. Within the same company, for example, a sales and marketing team may rely on a customer relationship management system to track customer orders but lack any visibility into production or logistics databases that report on delays and stockouts. Disconnects like this become even more likely with external supply chain partners.

Despite facing operational challenges, small and midsize businesses may put off technical solutions due to the up-front costs. According to an S&P Global analysis, while large enterprises may have the funds to try out emerging technologies, most businesses will not invest in digital supply chain transformation unless they can see a potential return within a reasonable time frame.

7 Types of Supply Chain Complexity

Experts break down supply chain complexity into seven essential types. Different types of complexity present unique vulnerabilities that call for specific interventions. A seasoned supply chain manager may understand this intuitively, from experience. Yet parsing each type of supply chain complexity can help hone planning, optimize operations and mitigate risks.

-

Structural Complexity

Structural complexity considers the involvement of the number and variety of all supply chain partners and where they are in the world. Participants include a company’s internal departments, direct suppliers and, in turn, their suppliers. Companies need to manage structural complexity in and of itself to yield better communication, collaboration and supply chain visibility. They should also understand and address structural complexity in terms of dynamic complexity and the other types of complexity described below.

-

Dynamic Complexity

Dynamic complexity factors in change, whether that change is caused by demand, weather or other conditions. Tracking, analyzing and forecasting dynamic complexity typically involves using modern technologies, such as IoT for real-time data collection and predictive analytics for decision support, which contributes to flexibility and responsiveness in supply chains.

-

Demand Complexity

Customer demand falls under the category of dynamic complexity, but it merits special focus. Companies have long struggled with demand complexity and the need to forecast and meet changing customer demands. Data-driven demand planning and forecasting have become more powerful with the growth of big data and predictive analytics, up to and including AI. Getting a better handle on changing trends in preferences for products, related services and even the way in which they are delivered can improve the management of supply chain functions, including sourcing, production and inventory.

-

Supply Complexity

What about the product itself? Is it simple or sophisticated? One-size-fits-all or customizable? Is it part of a large or small product portfolio? The greater the supply complexity, also known as product complexity, the higher the potential risks surrounding quality, cost and lead times. According to the PwC management consultancy, companies that rationalize their product complexity can achieve a 25% to 30% cost reduction in supply chain operations.

-

Process Complexity

Process complexity grows as the number and intricacy of steps in a supply chain increase. For example, sophisticated manufacturing, regulatory compliance monitoring and climate control maintenance can complicate handoffs from one supply chain partner or location to another. Processes that must be performed sequentially can run into bottlenecks if any one step falters. Many point to more transparent data sharing and automation, as ways to ease these and other process complexity challenges. Close supplier collaboration, process standardization and modular approaches can also counteract process complexity.

-

Environmental and Social Complexity

Governments, businesses and their customers have become keenly aware of the environmental and social harms that supply chains can cause — the majority of most companies’ carbon emissions, for example, are produced by their supply chains. Nearly half of supply chain professionals recently surveyed by Material Handling Industry (MHI), a trade association, said they are under increased pressure to make their operations more sustainable. Meanwhile, California has been leading the U.S. in regulating emissions reporting, with rules currently coming into effect for some companies. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission was set to follow with a new rule, too.

As for social complexity, companies doing business in Canada now have to report on their efforts to address forced labor and child labor in their supply chains. Similar requirements are expected to proliferate over time. Consumers are also exerting pressure on companies to adopt better environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices. One proof point: Research by the Nielsen polling company shows that products making ESG-related claims sell better than those that don’t.

Companies, in turn, are relying on various innovations to address environmental and social complexity. Among these are centralized systems for suppliers to input their emissions data and supply chain traceability tools, including barcodes and blockchain records, to verify product origins.

-

Information and Technological Complexity

Information keeps supply chains running, with inputs and updates flowing between and among a company’s departments, its partners and its partners’ partners. Data has to be shared about projected demand, inventory levels, the status of orders, the progress of a truck on its way to a port, the conditions at the port — and the list goes on.

Unfortunately, supply chain managers aren’t always working with good information. As Martin Christopher, an emeritus professor of supply chain management and logistics, wrote in his textbook on the subject, “The volume of data that flows in all directions [in supply chains] is immense and not always accurate and can be prone to misinterpretation. As a result of this distortion, the data that is used as input to planning and forecasting activities is flawed and hence forecast accuracy is reduced and more costs are incurred.”

Another shortcoming is that transparency is limited due to technological complexity. The many systems and data formats used in the supply chain can create silos and gaps at critical points.

One of the biggest complications that has emerged in the digitized supply chain is cybersecurity. Companies must protect their operations from cyberattackers, many of whom break into smaller suppliers with weaker defenses to gain access across a wider supply chain.

What Determines the Complexity of a Supply Chain?

Breaking down complexity even further reveals numerous root causes of potential friction throughout a supply chain, such as the number of process, stakeholders, locations, and systems involved. Specifically:

- Supplier base: With recent efforts to abandon single-source arrangements and add alternative suppliers to increase reliability, businesses are struggling to find a cost-effective balance between managing too few and too many suppliers.

- Interdependencies: The interdependencies among a company, its suppliers and its suppliers’ suppliers make it essential to strike the right balance, since supply chain partners engage in intense information exchange and other resource sharing to complete each phase of work and hand it off successfully to the next partner. Strategic sourcing techniques can help to reduce interdependencies or improve the quality of communications between and among partners.

- Number of components: Each additional component in a final product can require coordinating yet another supplier, transportation schedule and inventory plan. The delayed delivery of a single component can halt an entire production line in a manufacturing supply chain.

- Diversity of products and services: Similarly, complexity increases whenever a new product or service is added. Each presents its own challenges in sourcing materials, handling the complexity of components, coordinating the changing cast of suppliers, responding to fluctuating demand and fulfilling other needs.

- Process complexity: The many processes involved in a supply chain need to add up to one smooth flow, from procurement and manufacturing to warehousing and distribution. Notably, each of these processes breaks down even further into its own procedures for such essentials as contract negotiation, quality control and others.

- Customer demand variability: Suddenly emerging market trends, loss of consumer confidence in the economy and other shifts in customer sentiment create forecasting challenges and difficulties in balancing supply and demand across sourcing, production and warehousing.

- Geographic spread: The more nodes on a supply chain and the more national borders to cross, the less uniform and predictable are the necessary transportation and warehousing arrangements, customs clearing procedures and customer preferences.

- Regulatory environment: The supply chain bears a great deal of the burden of the diverse and continually shifting regulations imposed on businesses — with rules specific to everything from product quality and safety to sourcing, labeling, transportation and disposal. Notably, the regulatory environment changes from location to location.

- External forces: Beyond regulation, external forces, such as geopolitical conflicts, trade disputes and extreme weather, require the company’s constant vigilance and readiness to adapt.

- Organizational structure: Oppositional forces within an organization can be just as disruptive, fomenting strategic course corrections or revenue shortfalls that trickle out to supply chain budgeting and operations. Conflicting decisions made by disparate departments can also whipsaw a supply chain.

- Technological integration: Information silos can cripple supply chain decision-making and operations; conversely, integration can facilitate transparency, automation and data-driven decision-making.

- Innovation and product life cycle: Companies need to meet expectations that they will continually innovate and bring new products to market, which can cause many, if not all, of the above supply chain challenges to resurface.

11 Ways to Manage Supply Chain Complexity

Many see supply chain resilience as the antidote to the problems of today’s complex supply chains. According to BCG, enablers of resilience include the following:

- A geographically diverse footprint that ensures access to crucial resources and target markets

- Redundancy of suppliers

- Flexible sourcing and production

- Visibility into risks

- Rapid response to problems

Along these lines, the Wall Street Journal reported that companies are moving some of their production closer to where they expect to sell their goods, expanding their base of suppliers and automating supply chain functions. Companies have also developed bigger buffer stocks of inventory, after decades of prioritizing “just-in-time” deliveries in their supply chains.

Ironically, even supply chain resilience strategies can add complexity, requiring careful balancing of the benefits and risks inherent in adding suppliers, locations and new technologies. Here are 11 approaches to this balancing act.

-

Streamlining Operations

One key to managing supply chain complexity is to identify and manage the complexity that is necessary in the system while preventing and eliminating unnecessary complications. Streamlining operations can take many forms, such as standardizing purchase orders or procedures for selecting and onboarding new suppliers; automating repetitive tasks, such as order processing; and taking care to design efficient distribution networks.

-

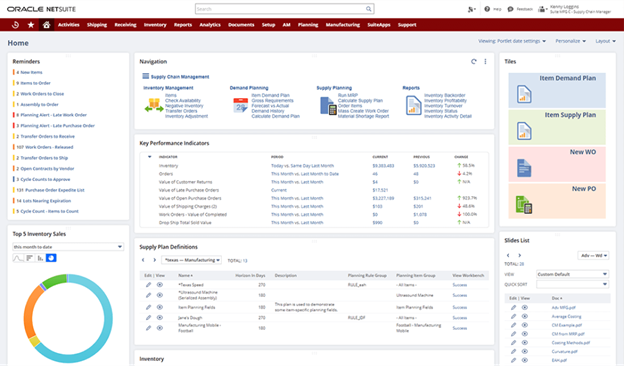

Technology Integration

The theme of technology integration recurs in nearly all advice on managing supply chain complexity. Supply chain management software should integrate with a company’s enterprise resource planning (ERP) system to better align all departments and suppliers. Companies can also host supplier portals to enable two-way information sharing on orders, shipment tracking, performance indicators and invoicing. Modern collaboration platforms can also facilitate scenario planning, modeling and other joint activities.

-

Supply Chain Design

BCG’s report, “Building the Supply Chain of the Future,” says it takes a comprehensive program to build a resilient supply chain that can better handle disruptions. “Such a program comprises network and product design, sourcing strategy and planning,” according to the market research firm. “And it must be able — through monitoring, prediction and crisis response — to move quickly when disruption occurs.”

-

Vendor Management

A recent article in the Harvard Business Review emphasized the need for companies and their suppliers to create flexible, dynamic relationships that can adapt to changing supply chain pressures. Enabled by technology platforms, these types of interactions should replace the point-to-point, static arrangements currently in place.

Disruptions can be avoided if companies position themselves to easily access alternative transportation routes with their current partners, for example, or reach out to alternative suppliers if inventory levels drop. A related supply chain trend involves new, more flexible models for contracts with vendors. These let buyers slice orders into smaller blocks, making it easier to adapt what they’re buying in line with volatile market forces.

-

Demand Management

Demand management identifies and forecasts customer demand to keep supply chain operations in sync with it. Getting it right can help with scheduling production and achieving the required level of inventory in the correct location, without creating costly surpluses. Other benefits may include the ability to obtain volume discounts based on confident demand forecasting. The ultimate benefit is customer satisfaction, as demand management reduces delays and stockouts.

A demand-forecasting exercise should involve collaboration with internal departments, such as marketing, but also with key suppliers. Data platforms can facilitate the sharing of orders, current inventory levels and forecasts within a company and with supply chain partners. Analytics are becoming increasingly powerful tools for forecasting, thanks to the growing use of AI.

-

Inventory Management

Inventory management should work hand in hand with demand management. The key added element here is supply chain visibility. A company’s ability to see how materials, components and products are flowing across its supply chain can reduce the risks of stockouts, overstocks, delays and other issues. Order fulfillment can be accelerated, earning greater customer satisfaction, and production and logistics can be optimized to reduce costs.

Tracking technologies play a significant role in inventory management, as RFID tags and other IoT sensors for transparency are combined with data analytics, which recognize normal patterns and identify where problems might be emerging. Shared platforms with suppliers facilitate a “single version of truth” on which buyers and sellers can base their operations.

-

Lean Management

Another inventory management tactic — namely, preserving “just-in-case” overstocks — gained favor in the wake of pandemic-related shortages. Until that time, most supply chain managers adhered to “lean” principles of minimal “just-in-time” inventory management. These days, though, experts say the pendulum is swinging back toward the middle. Many companies are taking a hybrid approach, since reliability is important but lean management is usually more cost-effective. Their supply chain managers are building more resilience into their networks with other methods than overstocking, such as using technology for better visibility and implementing stronger vendor management.

-

Collaborative Planning

Collaboration forms the bedrock for supply chain efficiency, whether within a company or across a network of trading partners. Without it, companies cannot achieve critical visibility and quality control. Nor can they enjoy benefits, such as joint problem-solving, when demand suddenly surges, a hurricane is in the forecast, a refrigerated truck breaks down or some other issue emerges.

In the current world of “fast fashion,” retailers rely heavily on supply chain collaboration, sharing their demand forecasts with manufacturers as early as possible. Some companies even enter a type of partnership with their suppliers, under arrangements known as vendor-managed inventory. This approach gives suppliers the responsibility to replenish inventory as needed — within agreed limits.

Clearly, arrangements such as these require careful vendor selection that includes weighing potential suppliers’ collaborative capabilities and cultures before entering a relationship. Then, vendor relationship management becomes pivotal, requiring significant time commitments and communication routines.

-

Regulatory Compliance

Collaboration also provides a basis for regulatory compliance. Under most circumstances, supply chains operate across different municipalities, states and countries — all of which have diverse requirements for product safety, environmental impact, data privacy and other business matters. And although a company may outsource some aspect of its supply chain, it cannot “outsource” its regulatory responsibilities.

Working closely with suppliers helps avoid the fines and reputational damage that result when a government declares a company to be noncompliant. Vendor selection and management should include compliance as a value to be assessed and monitored, and contracts should include compliance clauses. At the same time, a company’s own practices should also be governed by a compliance strategy that is actively monitored and regularly updated, especially in highly regulated industries.

-

Training and Development

A recent article in the Harvard Business Review reported skills shortages across all points of the supply chain, from “picking and packing” at the warehouse to designing and running an entire supply chain. Automation can fill some of the gap, but more than half of the professionals surveyed by MHI cited challenges in hiring and retaining qualified workers as a top concern with serious repercussions for supply chain performance. Some 40% said they are reskilling and upskilling workers to fill the need, often with staff development for new technologies. Universities, industry associations and others all offer supply chain training and certification programs.

Training programs can help build capacity for companies’ suppliers, as well as their own staff, in areas such as compliance. For example, the U.S. Department of Labor has outlined a social compliance training program for vendors, including topics such as self-audits and subcontractor disclosures.

-

Risk Management

At the end of the day, much of supply chain management aims to mitigate the risks inherent in these complex systems. Yet, supply chain risk management should also be addressed in a specific strategy that maps out robust processes for addressing negative events, such as supplier bankruptcies, cybersecurity breaches or the more mundane scenario in which a piece of factory equipment fails. Experts at the McKinsey consulting firm also advise developing a risk-aware and risk-averse culture.

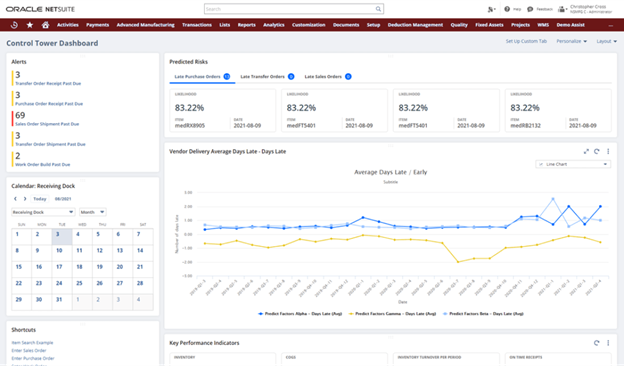

NetSuite Helps Businesses Manage Supply Chain Complexity

Cloud-based software has revolutionized supply chain management, extending greater visibility and control throughout even the most complex supply chains. NetSuite’s integrated ERP and supply chain solutions help companies navigate the intricacies of their supply chains, from securing materials to delivering finished products, ensuring that planning, procurement, production and other teams are all operating with the same real-time data. Suppliers can also access and input information, furthering transparency and coordination. Predictive analytics can identify risks, while scenario planning tools help determine how to respond.

Supply chain complexity can act as a major cost driver in business. And, as it increases due to modern pressures, taming complexity has become an ever-higher priority. Companies are employing multiple management techniques and technology tools to ensure that their supply chains weigh in as solid contributors — instead of persistent risks — to customer satisfaction, brand reputation and profitability. This work-in-progress is advancing rapidly, as new thinking in supply chain structure and innovations in their operation continue to prove themselves.

Supply Chain Complexity FAQs

What are the 8 sources of supply chain complexity?

Supply chain complexity increases due to the following drivers:

- Number of supply chain partners

- Diversity of products and services

- Number of components

- Process complexity

- Geographic spread

- Customer demand variability

- Regulatory environment and other external forces

- Technological integration issues

What is structural complexity in a supply chain?

Structural supply chain complexity results primarily from a proliferation of suppliers, products, processes and geographic locations in the supplier network, with numerous handoffs from one supply chain partner or location to another.

What are the factors affecting supply chain complexity?

Factors that can increase supply chain complexity include:

- Number of suppliers and logistics providers

- Quantity and location of supply chain nodes across the country and around the world

- Diversity of products

- Disconnections among technologies used by supply chain partners

Why are supply chains more complex?

Three factors have increased supply chain complexity in recent years: globalization/localization, alternative sourcing and increasing customer expectations. Specifically, supply chains grew in complexity as many companies globalized them in the past. Companies have also added alternative suppliers to hedge against risks inherent in the single-sourcing approach that was more commonly used in the past.