How flexible are you about the items you buy? Are there some purchases that you consider special, without substitute—and that you’re willing to make regardless of price? And other purchases that you’re willing to forego or swap for others when prices go up? Economists call this phenomenon elasticity of demand. It’s the relationship between the demand for a product and other factors, most often price. Understanding this relationship and how it affects buying behavior can help a business make smarter marketing decisions that increase sales.

What Is Elasticity of Demand?

Elasticity of demand refers to the shift in demand for an item or service when a change occurs in one of the variables that buyers consider as part of their purchase decisions. It’s a relationship between demand and another variable, such as price, availability of substitutes, advertising pressure, and customer income.

When a change in any one of those variables causes a significant alteration in demand for a product or service, its elasticity of demand is considered high. Elasticity shows that a customer’s buying behavior is highly flexible, or stretchy—like an elastic waistband. The more willing customers are to change purchasing decisions, the more elastic a product or service is. If a customer is willing to buy a different brand of coffee simply because it’s on sale that week or completely forgo buying coffee because its price has gone up, coffee can be said to have elastic demand.

In contrast, products that are inelastic do not experience large shifts in demand due to changes in their purchase-consideration variables. Customers remain rigid or firm in their buying choices for certain products and are unwilling or unable to be flexible. Tobacco products and utilities are classic examples of inelasticity of demand because, most times, a change in price or increase in advertising won’t significantly influence consumer demand.

Key Takeaways

- Elasticity of demand describes the potential for variation in demand for a product or service arising from changes in price, customer income, advertising, and other related factors.

- Many factors influence elasticity, such as price, availability of substitutes, necessity, brand loyalty, and urgency.

- Understanding elasticity of demand can help guide a business’s marketing and selling strategies to maximize profitability.

- Executing tactics to influence demand requires keen market insight and robust data for analysis.

Elasticity of Demand Explained

Elastic demand equates to flexibility in purchasing decisions—whether in quantities purchased, the chosen brand, or product substitution. Inelastic demand is unwavering, up to a point. For this reason, reducing elasticity is often considered to be a marketer’s primary goal: to position a product as so essential that customers keep buying it in most circumstances. Imagine a business that can increase its product price without a significant falloff in demand. Or one with customers so loyal that they continue to purchase in the same quantity, even when their own income drops. Understanding elasticity helps move the needle toward inelasticity.

Certain industries are said to be recession-resistant, largely because their products are inelastic: Demand for those products remains constant despite any economic downturn. Healthcare, utilities, and certain “vices” like alcohol and tobacco are items that tend to have consistent demand, regardless of price or the customer’s income. They also tend to generate high brand loyalty or barriers to switching, adding to customers’ unwillingness (or inability) to swap brands, as with doctors and utilities.

Why Is Elasticity of Demand Important?

Elasticity is a critical aspect of customer behavior, whether your customers are other businesses or individual consumers. At its core, elasticity measures the responsiveness of demand—how much customer purchasing changes in reaction to shifts in price, income, advertising, or the availability of related goods. Understanding the various types of elasticity offers valuable insights for operations managers and marketers who need to anticipate these changes. This knowledge helps them make the most of opportunities or insulate their products and services from potential risks. Elasticity is a key driver behind many internal decisions, including pricing and product positioning. It is essential to consider elasticity alongside other market dynamics to remain competitive and aligned with customer needs.

How Does Elasticity of Demand Work?

Economists have studied the elasticity of demand for decades, using various equations to measure the cause-and-effect relationship among factors such as price, income, and consumer purchasing behavior. (These formulas are discussed in later sections.) But what does elasticity look like in the real world of everyday businesses?

In one example, the Center for Food Demand Analysis and Sustainability (CFDAS) at Purdue University tracked how egg prices have affected sales over the past few years. It found that even when prices surged by as much as 60%, sales remained steady, concluding that eggs are inelastic. CFDAS further supported this determination by observing that there are few (if any) substitutes for eggs, which are also well-known for delivering a unique nutritional profile. The takeaway: Egg producers have a lot of latitude to raise prices in response to operational challenges, such as the avian flu, without risking a major drop in revenue.

The fast-food industry paints a different picture of elasticity. Industry analysts suggest that the plethora of fast-food substitutes was a key factor when one burger giant’s sales declined after raising its prices by more than 2%. Despite strong brand recognition, many customers decided to drive a little farther down the road to a competitor, rather than paying slightly more. This cautionary tale underscores why understanding the elasticity is especially important in certain industries, regardless of company size.

That said, elasticity isn’t always a fixed outcome, so it’s vital to really know your customer. One regional fast-food chain managed to buck the expected outcome by building intense brand loyalty. When rising minimum wage laws forced it to increase its prices, its revenue held strong, thanks to a deeply loyal customer base. This suggests that marketers may be able to “brand” themselves out of typical elasticity patterns and cushion the impact of external pressures on sales.

How Is Elasticity of Demand Used?

Elasticity of demand acts as a lens through which decision-makers can anticipate consumer behavior; therefore, it has many practical applications. Businesses apply it to maximize revenue and remain competitive, using it to guide pricing, production, and marketing decisions. Governments also leverage elasticity to achieve policy objectives.

In pricing strategy, businesses consider elasticity to determine how much flexibility they have in raising or lowering prices. The more inelastic the product is or is perceived to be by loyalists, the easier it is for companies to raise prices without triggering a decline in sales volume. Conversely, businesses dealing with elastic goods, such as luxury cars, often lower prices or offer promotions to stimulate demand. Some industries, such as airlines and rideshare services, apply elasticity through dynamic pricing, charging different prices to different customer segments not only based on their sensitivity to price, but also in response to real-time supply and demand conditions. This approach helps companies maximize revenue by aligning prices with what each group is willing to pay—the ultimate pricing application of elasticity of demand.

Elasticity also plays a crucial role in competitive strategy. Businesses that operate in markets with close substitutes, such as the fast-food chains discussed in the prior section, closely monitor competitors’ prices, since even small changes can cause a chain reaction in customer purchasing. For these highly elastic products, marketing efforts may emphasize product differentiation or brand loyalty to reduce elasticity.

In addition, businesses use elasticity to operate more efficiently. Incorporating elasticity of demand models makes revenue projections more realistic. Armed with better demand forecasting, companies might decide to adjust production schedules and inventory levels, so as to reduce waste or avoid stockouts.

Governments also use elasticity to shape effective tax and subsidy policies and to influence constituent behavior. Lawmakers opt to tax inelastic goods, such as tobacco or gasoline, because they know that consumers are less likely to change their buying behavior, which keeps tax revenue stable. In contrast, taxing elastic goods, such as large, sugary beverages, may be an effective way to encourage a public health goal of reducing consumption. Similarly, public subsidies, such as tax credits for electric vehicles, are often attached to goods with elastic demand, motivating adoption by making them more affordable.

4 Types of Elasticity

There are four types of elasticity, categorized by the instigating variable—price, related products, customer income, and advertising. Formulas for calculating each type of elasticity can be used for scenario-planning or retrospective analysis, but it’s important to note that customer behavior is not an exact science and predictions can be difficult.

-

Price Elasticity of Demand (PED)

When customers are highly sensitive to changes in price, there is a high PED. This means, for example, that if inflation causes prices to increase, customers will reduce the quantity they purchase by switching, substituting, or skipping. Conversely, it can also indicate that a reduction in price may spur additional sales. The formula for PED is:

PED = % change in quantity / % change in price

Or

PED = [(Q2 – Q1) / Q1] / [(P2 – P1) / P1]

Q1 = initial quantity of demand

Q2 = new quantity of demand

P1 = initial price

P2 = new price

For an application of this formula in action, see the example section, below.

-

Cross Elasticity of Demand (XED)

Cross elasticity happens when changes if one product’s price prompt changes in demand for another. The two products must be related, either as complements or substitutes for each other. When products are substitutes for each other, a rise in the price of one will usually cause a rise in demand for the other. For example, if coffee prices rise, then demand for breakfast tea is likely to increase as customers substitute tea for coffee. When two products are complementary, a rise in the price of one will usually cause a decrease in the demand for the other. Similarly, if coffee prices rise, demand for coffee creamer will likely decline as people drink less coffee. XED does not apply to unrelated products, such as airline tickets and oranges. The formula for XED is:

XED = % change in quantity for product A / % change in price for product B

Or

XED = [(Q2a – Q1a) / (Q2a + Q1a)] / [(P2b – P1b) / (P2b + P1b)]

Q1a = initial quantity of demand of product A

Q2a = new quantity of demand of product A

P1b = initial price of product B

P2b = new price of product B

-

Income Elasticity of Demand (YED)

YED (with a “Y” because that’s the notation economists use for income) is the relationship between demand and a customer’s income. As income decreases, quantity of demand tends to decline, even if all other factors remain the same, including price. YED tends to differ according to the priority of a product, meaning that what economists refer to as “normal goods,” such as food, clothes, and other necessities, are likely to be prioritized over luxury items when customers’ income declines. Further, spending on normal goods is more likely to increase first when income increases, and increase of luxury goods happens on a lag. The formula for YED is:

YED = % change in quantity / % change in income

Or

YED = [(Q2 – Q1) / Q1] / [(Y2 – Y1) / Y1]

Q1 = initial quantity of demand

Q2 = new quantity of demand

Y1 = initial income

Y2 = new income

-

Advertising Elasticity of Demand (AED)

This type of elasticity focuses on the relationship between customer demand and a seller’s advertising. It’s a measure of advertising effectiveness that assesses whether increases in advertising elevate customers’ impressions to the point where they respond by buying more. The formula for AED is:

AED = % change in quantity / % change in advertising

Or

AED = [(Q2 – Q1) / Q1] / [(A2 – A1) / A1]

Q1 = initial quantity of demand

Q2 = new quantity of demand

A1 = initial advertising expenditure

A2 = new advertising expenditure

5 Categories of Elasticity of Demand

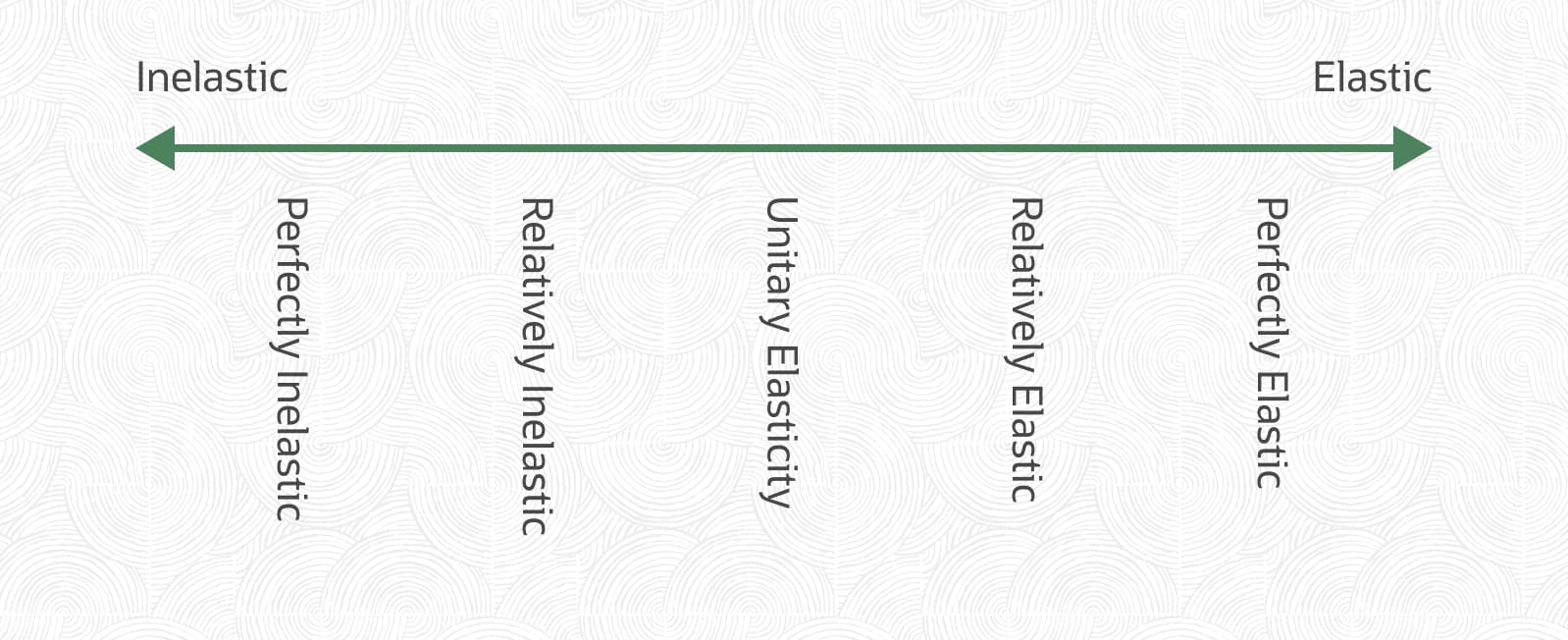

Economists describe elasticity as a spectrum of customer sensitivity, calibrated into five categories using “relative” and “perfect” to describe the level of elasticity. Any product’s or service’s elasticity lands in one of the five categories, based on the values produced by the formulas above and by its demand curve. Because the formulas are independent of each other, even when applied to the same product, the different types of elasticity—price, cross, income, and advertising—may end up in different categories for the same product or service. The elasticity of demand spectrum starts at the left with perfectly inelastic demand, ends at the right with perfectly elastic demand, and has unitary elasticity at its theoretical center. The descriptions below use the price elasticity formula-PED-to illustrate the value for each category, because price elasticity is the most widely used type of elasticity in business and because the other types can become far more complex to interpret. For example, income elasticity requires additional dimensions to visualize because different curves apply to people at different income levels.

-

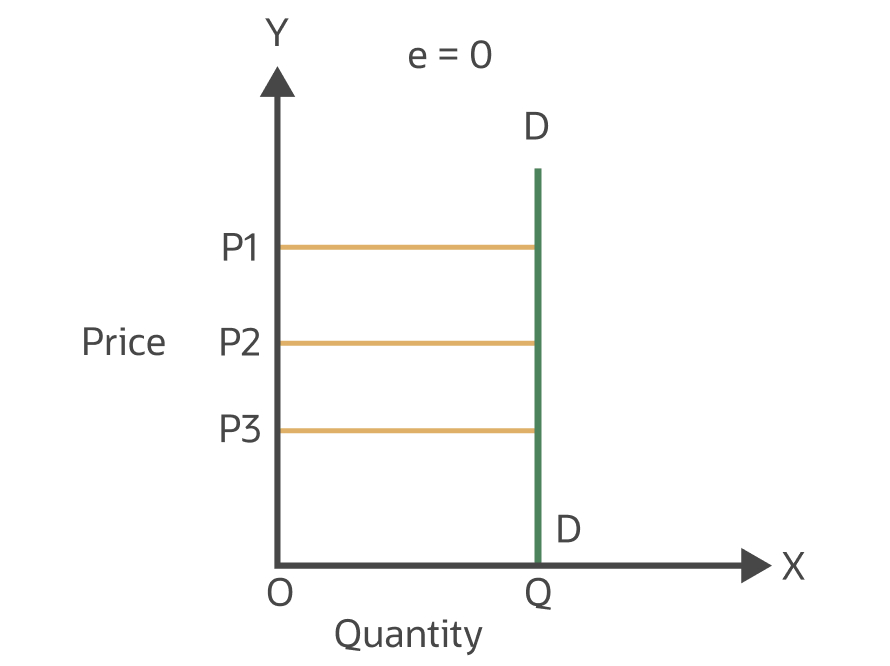

Perfectly inelastic demand

Perfectly inelastic demand is when demand does not change, regardless of changes in other factors. Products that are considered a necessity, with no substitutes, are in this zone, such as essential foods and lifesaving drugs. Perfectly inelastic demand has a PED of zero.

This graph illustrates a perfectly inelastic demand curve (labeled D) where the quantity demanded (Q) remains constant regardless of price changes (P1, P2, P3), indicating an elasticity (e) of 0. -

Relatively inelastic demand

Relatively inelastic demand means that it takes large changes in a factor, such as price, to cause a small change in demand. Gasoline and salt are common examples of relatively inelastic products. Relatively inelastic demand has a PED of less than one.

This graph depicts an inelastic demand curve (e<1) where a change in price (P1 to P2) leads to a proportionally smaller change in quantity demanded (Q1 to Q2). -

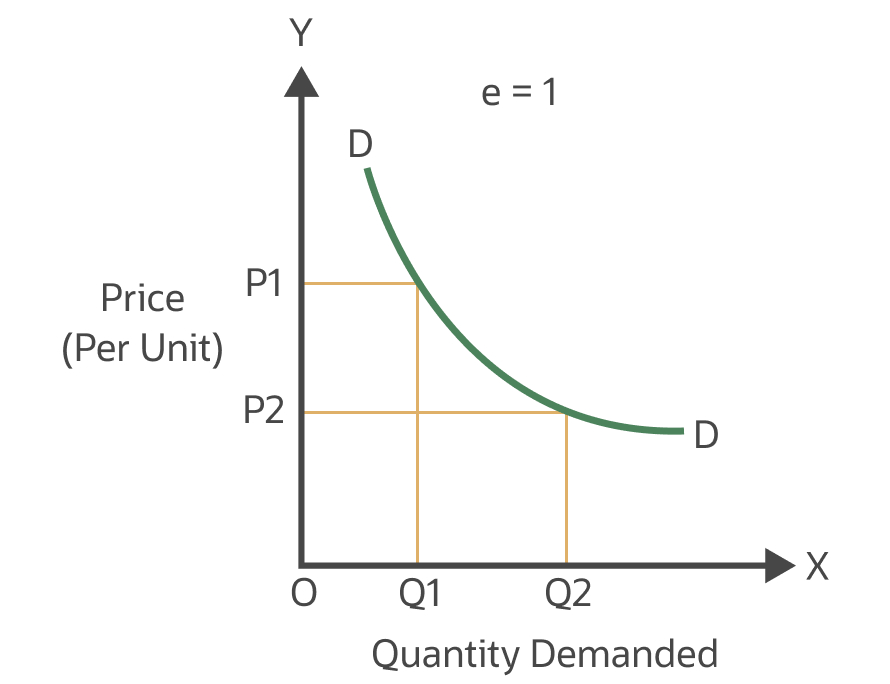

Unitary elastic demand

Unitary elastic demand is a special case that arises when the impact on demand is an equal, one-for-one change compared with another factor. For example, a 10% increase in price causes a 10% decrease in demand quantity. Unitary elastic demand is mostly a hypothetical concept, since it is unusual to find a product with such perfect correlation. Unitary elastic demand has a PED of exactly one.

This image displays a two-dimensional graph illustrating a unitary elastic demand curve in economics, where the elasticity of demand is exactly 1. -

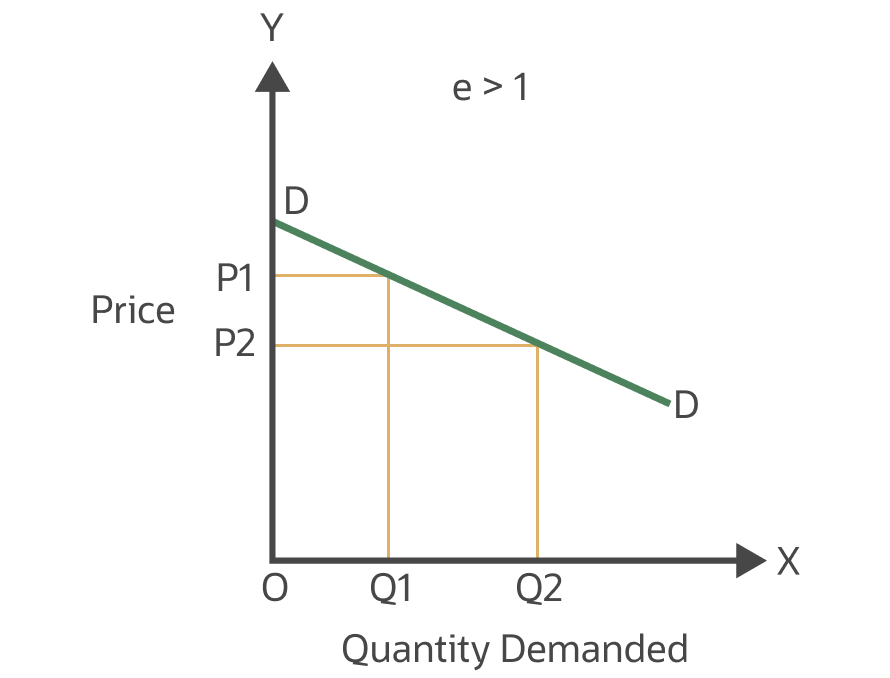

Relatively elastic demand

Relatively elastic demand means a small change in one factor creates a disproportionately larger change in demand. For example, if a 5% increase in the price of a streaming service caused a 10% decrease in subscribers, it would be considered relatively elastic. Most products and services fall into this zone. Relatively elastic demand has a PED greater than one. Higher values indicate greater elasticity.

This image displays a two-dimensional graph illustrating a relatively elastic demand curve, where the elasticity of demand is greater than 1. -

Perfectly elastic demand

Perfectly elastic demand is the extreme scenario where demand drops 100% due to changes in one of the factors. This is relatively rare, since characteristics such as accessibility, brand loyalty, and quality will often cause some customers to continue to purchase a product. As an example, if the price of organic bananas goes up at Fred’s Supermarket but not at Barney’s Grocery, under perfect elasticity of demand no shoppers would purchase the bananas at Fred’s. However, some customers might decide to pay the higher price to save time and effort, especially if they believe Fred’s produce is fresher. The result of the PED calculation for perfect elasticity is infinity—representing the all-or-nothing buying decision.

This graph shows a perfectly elastic demand curve (e=∞), where any price change from P results in an infinite change in quantity demanded.

What Determines Elasticity of Demand?

Elasticity of demand is influenced by several determinants to which customers respond with differing levels of intensity.

- Availability of substitutes: When customers perceive that a product lacks significant differentiation or is easily substituted, the product tends to have a higher elasticity of demand. This means customers will easily swap one brand for another or one product for another. A good example is the plethora of breakfast cereal substitutes, from swapping flakes for O’s to switching to granola bars. The opposite also holds true: Products that have no substitute, such as gasoline, are highly inelastic.

- Urgency of purchase: When customers are not in a rush to make a purchase, they can put it off if prices are increasing. This means a higher elasticity of demand exists for optional or discretionary purchases. Conversely, when a purchase is urgent, such as plumbing services for a leaky pipe, customers are more willing to pay a higher price in return for quicker service. Their viewpoint is inelastic.

- Duration of price change: Customers react differently to price changes that are expected to last a short period of time versus a long-term shift. Flash sales that are perceived to be short-term can cause greater increases in demand than discounts that are expected to be around longer. Consider the changes in demand around Black Friday and Cyber Monday.

- Percentage of income: Purchases that represent a higher percentage of a household budget tend to be more elastic than those that are smaller. For example, customers demonstrate a higher level of price elasticity when buying furniture than when purchasing computer paper. The same percentage of change in price would cause a greater change in demand for a couch than for paper because a couch is a bigger-ticket item relative to the customer’s income.

- Necessity: The essential/inessential nature of goods is a primary driver of elasticity. Customers tend to have unchanging levels of demand for products they consider essential. Customers will be rigid when purchasing products considered indispensable for survival or quality of life. Conversely, buying habits tend to be more elastic for luxury goods. This dynamic occurs, in part, because purchasing necessities cannot be postponed. Addictive products, such as alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, are an extreme variation of inelasticity caused by necessity.

- Brand loyalty: When customers have a high level of brand loyalty, they are less likely to swap brands, resulting in a higher level of inelasticity of demand. This typically happens when substitutes are perceived to be of inferior quality or a poor match, so customers are willing to pay a little more rather than reduce their demand. Marketers focus on these characteristics when positioning their products. Items seen as commodities, where one brand is the same as the next, have a higher level of elasticity of demand, and therefore their sales fluctuate more significantly with price.

- Buyer: The “other people’s money” concept shows that the same product may be susceptible to different levels of price elasticity depending on who pays for the goods. Customers tend to be more willing to pay higher prices when they aren’t the one actually paying for the product, such as for company-reimbursed travel and entertainment.

Example of Elasticity of Demand

The following example provides a common scenario that illustrates the application of price elasticity of demand.

KMR Inc. is in the online retail shoe business. In 2023, KMR sold 1,500 pairs of snow boots at an average price of $100 per pair. During 2024, KMR lowered the price to $90 and sold 1,800 pairs. In both years, KMR’s cost of goods sold was $40. The price elasticity of demand can be calculated as:

PED =

% change in quantity / % change in price

PED =

[(Q2 – Q1) / Q1]

/ [(P2 – P1)

/ P1]

Q1 = 1,500

Q2 = 1,800

P1 = $100

P2 = $90

= [(1,800 – 1,500)

/ 1,500] / [($90

– $100)]

/ $100

= 0.2 / 0.1

= 2

The calculation above indicates that the snow boots are relatively elastic since the change in volume exceeded the change in price. The volume sold increased by 300 pairs (20%) when the price dropped by $10 (10%).

Whether this change was beneficial for KMR’s business is subject to interpretation. In this case, the price change increased volume and helped KMR increase total snow boot revenue from $150,000 ($100 x 1,500) to $162,000 ($90 x 1,800), an increase of $12,000 (8%). However, KMR’s gross profit remained the same: 2023 = $90,000 [($100–$40) x 1,500]; and 2024 = $90,000 [($90–$40) x 1,800]. Of course, a larger volume of business may bring along other additional costs of operations, beyond the cost of goods sold.

Prepare Your Business for Any Economic Condition With NetSuite Financial Management

Elasticity of demand is a foundational concept for business leaders to consider and manage. The conventional wisdom of “demand goes down when prices go up (and vice versa)” has limitations and nuances that are better addressed by the concept of elasticity. Understanding how much demand might change due to price increases or during periods of contracting customer incomes is a crucial objective for many organizations. This analysis requires keen market insight and reliable internal data. NetSuite Cloud Accounting Software provides real-time access to transactional data in greater detail and at high levels. When combined with customizable dashboards, it can help business managers keep a close eye on changes in the business.

Elasticity of demand refers to how sensitive a customer’s purchasing behavior is to changes in multiple buying factors. The most common factor is price, although other variables, such as brand loyalty, availability of acceptable substitutes, necessity, and urgency, also influence elasticity. Business leaders need to understand the demand elasticity of their products when setting prices and developing product positioning. Formulas and calculations do a good job at estimating elasticity of demand but require high-quality data to be useful for management decision-making.

Elasticity of Demand FAQs

What makes a product elastic?

Elasticity of demand is a metric that demonstrates the sensitive of a customer’s purchasing behavior in relation to changes in one or more buying factors, including price, brand loyalty, availability of acceptable substitutes, necessity, and urgency.

What effect does elasticity of demand have on total revenue?

Revenue is the product of selling volume and price. When price goes up and volume remains constant, revenue increases. Conversely, when price goes down and volume remains constant, revenue declines. Elasticity may initiate a compensating uptick in demand when prices go down, causing revenue to be constant or even increase.

Why is it called elasticity of demand?

Elasticity of demand refers to the variation in demand for an item or service when a purchase-decision variable changes. It’s the relationship between demand and variables, such as price, availability of substitutes, advertising impressions, and customer income. When a change in any one of those variables causes a significant shift in demand, the elasticity of demand is high—meaning the customer’s buying behavior is flexible. When changes in these variables have little or no effect on demand, the product is inelastic.

Is elasticity of 1 inelastic?

An elasticity of 1 is not inelastic—it’s called unitary elastic demand. This is a special case of relative elasticity where the effect on demand is an equal, one-for-one change compared with a variation in one of the buying factors. For example, a 10% increase in price causes a 10% decrease in quantity demand.