There's no foolproof way to predict a recession. But paying attention to important indicators can provide insights into the health and direction of the economy, which in turn speaks to the likelihood of a recession. Such insights can be — and are — used for decision-making at every level, from personal to business to governmental policy.

This article offers detailed explanations of the most important commonly cited recession indicators that appear in the news and in economic forecasts.

What Are Recession Indicators?

Recession indicators are a subset of economic indicators that provide information on the future likelihood, presence or severity of an economic recession. There are hundreds, maybe even thousands, of regularly reported or calculated statistics that could be considered recession indicators, plus proprietary models used by forecasters and analysts.

What these statistics all have in common is they measure factors that matter to economic health, from factual data about interest rates, manufacturing output and retail purchases to indexes that capture consumer emotions, such as confidence in the economy. Some indicators are considered "eading," meaning they can suggest whether a recession is on the horizon. But many, if not most, merely tell you when a recession has arrived.

Key Takeaways

- Recession indicators are economic indicators that speak to the probability, presence or severity of a recession.

- No one indicator, or known combination of several indicators, provides an always-accurate prediction of when a recession will happen.

- Recession indicators can tell you a lot about whether the likelihood of recession is increasing or decreasing, whether different components of the economy are getting stronger or weaker and where there might be trouble that could lead to a recession.

- Recession indicators cover many aspects of the economy, from financial markets to manufacturing to sales to employment.

Recession Indicators Explained

Let's get this out of the way first: There's no such thing as a perfect recession indicator. A perfect recession indicator, by definition, must:

- Have a false-positive rate of 0%, meaning every time it predicts a recession, a recession happens.

- Have a false-negative rate of 0%, meaning there is no chance of a recession unless the indicator says so.

- Tell you in advance when a recession will happen (as opposed to telling you that one is happening now or happened before).

You may see bold claims about indicators being "always right," but those don't hold up to scrutiny on all three factors. However, recession indicators can tell you a lot about the health and trajectory of an economy. They speak to the health of labor markets, financial markets, manufacturing operations and even the sentiment and mood among important economic actors, like retail consumers or small businesses. Taken together, recession indicators can paint a vivid and detailed picture of economic happenings. Close observers will glean even more from them, over time, by becoming familiar with their trends and identifying deviations from expectation.

Each indicator has its own limitations, be it a source of error, a blind spot or a focus on a small piece of the whole picture. Some recession indicators try to take a broader view, but in doing so important information and nuance is lost.

Importantly, many recession indicators are based on expectations and economic theory. But just because there's a consensus expectation for something to happen doesn't mean it will (though recessions can sometimes be self-fulfilling prophecies). Likewise, just because a theory predicts something doesn't mean it will happen in the real world, which usually deviates from theoretical models. And no recession indicator rooted in economic data can predict sudden adverse changes in the world — like a global pandemic — that can bring on a recession regardless of whether indicators are flashing warning signs or promising calm seas ahead.

Indicators vs. Causes of a Recession

When discussing economic indicators, it's easy to use language that confuses prediction with causation. If an indicator very frequently flashes warnings right before a recession, people might believe it causes recessions. In the case of a "self-fulfilling prophecy" recession, in which negative expectations alter behavior until those negative expectations are met, that can be true. But, in general, the causes and indicators of a recession are separate. Indicators measure. They're collections of data, indexes of stock prices, the results of fielded surveys or calculations performed on consistently reported observations.

Recession causes can sometimes be seen in the indicators. Recessions caused by financial factors, like the Great Recession of 2008, often come with warning signs that can be seen ahead of time in data. But it was factors in the real world — people not being able to pay debts, some even losing their homes and a sudden contraction of credit being offered by lending institutions — that reverberated through our financial system and caused such tough economic times for a few years beginning in 2008. Though indicators may portend a recession, with very few exceptions they're separate from the causal factors.

11 Recession Indicators to Know in 2022

While it's probably impossible to create a comprehensive list of every recession indicator, the following list is representative of the types of economic factors that forecasters, economists and financial journalists look to when assessing the possibility of a recession. Some of these are specific indicators, while others represent categories.

1. The Yield Curve

An "inverted yield curve" is thought to be a harbinger of bad economic times. Yield-curve inversions have a good track record of predicting recessions and tend to give their signals with decent advance notice, making it a leading indicator. But the yield curve is also one of the hardest indicators for someone not versed in finance or economics to understand. What is a yield curve? What does it mean when the curve is inverted? For that matter, what does yield even mean in this context?

In this case, "yield" refers to the rate of return offered by a fixed income investment, such as a bond or CD. When people talk about "the yield curve," they're usually referring to the yields of securities issued by the U.S. Treasury. These could be investments that "mature" (i.e., pay investors back) in a month, year, decade or even 30 years. A yield curve is the shape you get by plotting the yields of those securities as a function of their time to maturity. There are a multitude of different possible yield curves but all are based on a comparison of short-term and long-term interest rates. That short/long comparison is interesting because economic theory says (and market behavior generally demonstrates) that long-term borrowing carries more risk than short-term borrowing, and so therefore the interest rates for long-term bonds must be higher than the rates for short-term bonds. But actual rates are set by market forces. And every once in a rare while, economic conditions are such that investors are willing to accept lower yields for long-term bonds than for short-term ones. When that happens, economists say the yield curve is "inverted" and some forecasters start exclaiming, "The recession is coming! The recession is coming!"

Why does an inverted yield curve often portend a recession? It comes down to the factors that could make bond yields fall. There are two main mechanisms by which this could happen:

-

The market mechanism:

If investors feel markets are too risky, they compensate with a "flight to quality," and many pour money into Treasury bonds. That increased demand causes the bonds' prices to rise — and when bond prices rise, their interest rates fall.

-

The policy mechanism:

The central bank — in the U.S., the Federal Reserve — can cause yield curves to invert. If the Fed lowers the Federal Funds Rate and signals it will keep it low, other interest rates throughout the economy will fall, too. If it raises the rate, other rates rise. If the Fed is maintaining high rates or raising rates but investors expect the future to have lower interest rates, yields on long-term bonds will drop. But the short-term bonds are going to be more closely anchored to the current Fed Funds Rate, and so the yield curve inverts. Why might people expect the Fed to lower rates precipitously? Lowering interest rates is a common policy move to combat a recession because it lowers the cost of borrowing for businesses and individuals, making new investments more feasible.

Either mechanism would indicate that an economic pullback is expected.

An inverted yield curve is best interpreted as a sign that tougher economic times are expected ahead, but it's not foolproof. Even when accurate, it doesn't say whether those tougher times will materialize in weeks, months or years. In the accompanying chart, for example, every time the curve dips below the 0% line, the curve is considered inverted. But while recessions (indicated by the gray shading) seem to inevitably follow, they sometimes arrive only after several years and/or multiple inversions. Nevertheless, the yield curve is still one of the best tools available to forecast a recession.

Yield Curve of 10-Year vs. 2-Year U.S. Treasury Bonds, 1976-2022

This yield curve plots the difference between the interest rates of 10-year and 2-year Treasury bonds; when the difference falls below zero, 2-year bonds have higher annualized returns. Recessions generally follow.

2. Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

GDP is a measure of the financial value of all the goods and services produced by a national economy. It's not a perfect measure; for example, hiring someone to clean your home counts toward GDP but doing it yourself does not, even if the same labor went into it and the same value was created.

Nonetheless, GDP is a consistent, widely used way to track the economic output of an entire country and one of the main indicators policymakers and economists look at to determine what is and isn't a recession. When GDP is shrinking sharply and/or consistently, that usually means a recession is happening. Two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth is a good rule of thumb to indicate a recession, though in the United States, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) looks at many other metrics, too, before declaring a recession. NBER declared the two-month period from February to April 2020 a recession due to the steep pandemic-induced decline in economic activity, even though it was far shorter than the two-quarter GDP criteria.

Because GDP is the primary way we measure recessions, it's an extremely accurate indicator. But it's not that helpful in predicting recessions, since at best it tells you "a recession is happening" and more often helps economists retroactively declare, "The recession started X months ago." As you might imagine, GDP is not trivial to measure and calculate, so initial quarterly measurements come out on a lag and are usually adjusted after as more clarity about that quarter's economic activity is obtained.

U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), January 1947 - October 2021

.jpg)

The U.S. economy has grown consistently for the past 75 years, interrupted 12 times for recessions of relatively brief duration (depicted as gray columns the width of which indicates the length of the recession).

3. Confidence Indexes

A confidence index is an intuitive way of measuring how people and organizations are feeling about the economy: Researchers randomly select a group of people and just ask, "How are you feeling about the economy?" Of course, it's a little more complicated than that to make sure the survey results are statistically valid, but that's the general idea. The value of confidence indexes comes from compiling the results in a consistent way over time so that meaning can be deduced from year-over-year and even decade-over-decade comparisons.

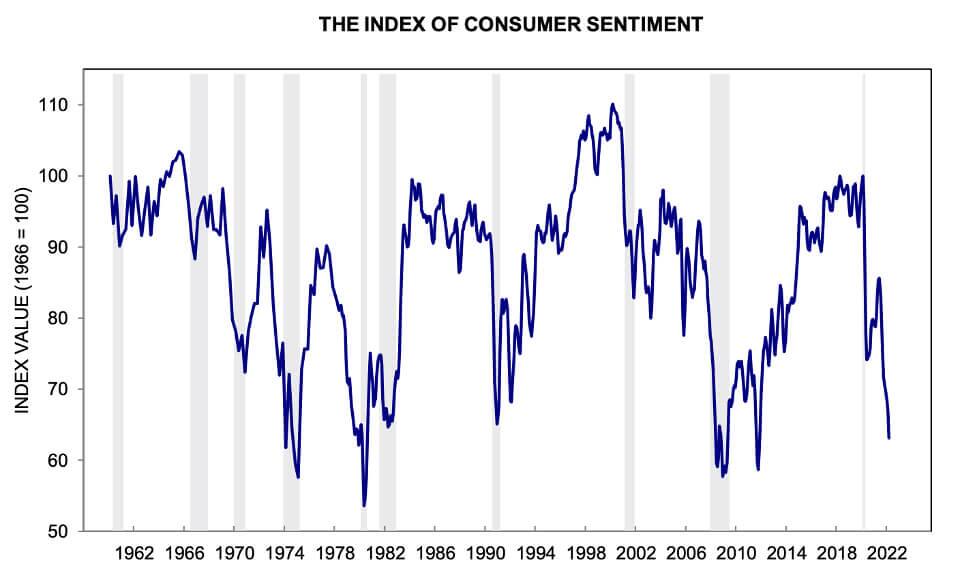

There are confidence surveys of businesses large and small, but the best-known and most-watched confidence index is the University of Michigan Index of Consumer Sentiment. This now-monthly survey was initiated in 1946. Its 50 core questions produce a treasure trove of data for economists and forecasters alike, but the key result is a single number. When that number rises, it means survey respondents are feeling more optimistic about the economy. When that number goes down, it's a sign of increasing economic pessimism. As an added treat for avid fans of economic surveys (we exist!), Michigan's December report usually includes an annual poem in the style of 'Twas the Night Before Christmas — though the future of this tradition may be uncertain given the December 2021 poetic resignation of Richard Curtin, who directed the survey for more than 45 years.

Confidence indexes can be surprisingly good forecasters of recessions, but not because a randomly selected American consumer has clairvoyance about the nation's economic future. Rather, it's that the aggregated behavior of consumers plays a large role in driving economic conditions. If the average consumer is cautious, fearful and/or experiencing a drop in income, that suggests the overall economy is going to be slowing down too.

For confidence indexes that survey businesses, a similar logic applies. The aggregate experience and outlook of many businesses is a good bellwether, even if the experiences of any one business could be misleading. In any economy you'll see some businesses thriving while others struggle, but the majority experience can be quite telling.

The University of Michigan Index of Consumer Sentiment usually declines just before and during a recession.

4. Real Income

Real income is an inflation-adjusted way of measuring how much purchasing power consumers have in their pockets. Where a measure of consumer confidence gives forecasters an idea about how comfortable consumers feel spending what they have, real income provides a more complete picture of how much consumers are actually earning that can be spent. If real income starts declining, that can be a sign a recession is coming. In more severe recessions, one might expect the biggest drops to occur once the recession is well underway.

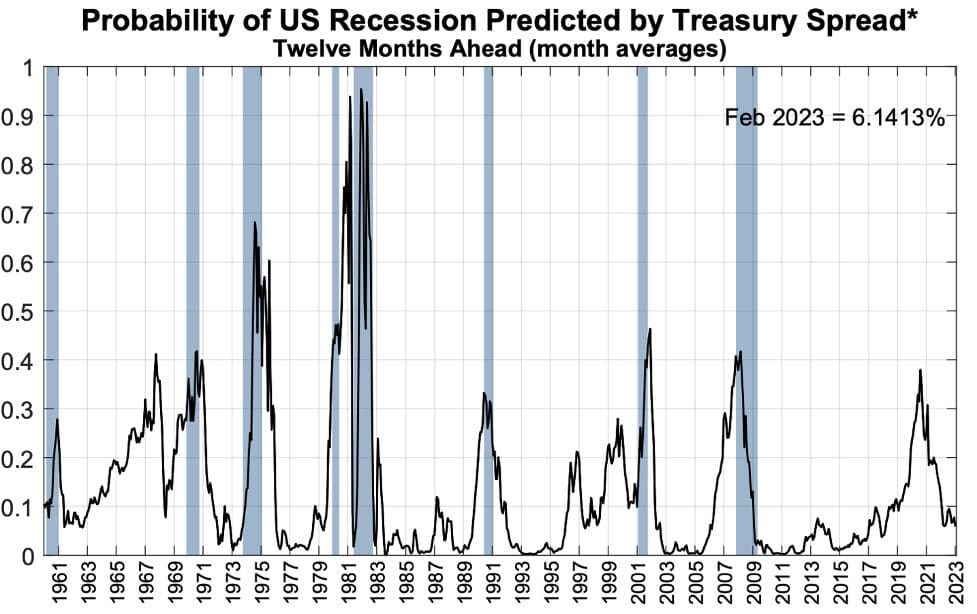

5. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York's Recession Probability Model

This subhead might make you think, "Great, the Fed has crunched all of these recession indicators into a single model to determine the probability of a recession! I can just look at this and ignore the rest." But, sadly, no. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York does indeed publish a probability model, but that model is based entirely on the yield curve. It does a good job of applying statistical models to historical data in order to turn the yield curve's slope into an implied probability of a recession in the next 12 months, but the drawbacks here are similar to those of just analyzing the yield curve itself.

The model is usually updated monthly. Here's a historical chart of model-generated probabilities of a recession through March 2023, based on data as of March 2022.

The Fed's recession probability model is based entirely on the yield curve. A value of 0.5 or higher should signal a coming recession. The model has a relatively spotty record of predicting recessions.

While every spike above an implied probability of 50% (0.5 on the chart) does correspond to a recession, the signal is not always given in advance. And plenty of recessions happen without the model ever signaling a probability above 50%. You may see an economist offer an opinion along the lines of, "Anything above 30% means you're more likely than not to see a recession in the next 12 months." If true — and looking at the chart, it seems to be true more often than not, though the sample size, meaning the number of recessions, is quite small — this means the output probabilities of the model are not well-enough calibrated to rely on as your primary forecast, since something with a 30% probability should, by definition, happen less than half the time. Again, though, the small sample size means it's hard to draw any conclusions yet about this model's overall accuracy.

6. Manufacturing

There are several measures of manufacturing that are useful economic indicators for assessing the trajectory of an economy, though they don't capture services or goods like software that don't require manufacturing.

One of the most common economic indicators for manufacturing is the ISM Manufacturing Index, which is computed using data from a survey put out by the Institute for Supply Management (ISM). The goal is to measure monthly changes in demand by polling manufacturers about the demand they're experiencing at their factories. ISM polls hundreds of purchasing managers at manufacturing companies for this index, which is why you may sometimes see it referred to as the PMI, or Purchasing Managers Index.

Because the survey captures information about orders not even started yet, it's often a good leading indicator for the direction of the economy. Measuring the throughput of supply chains by starting as upstream as possible should give a little more warning (especially when it comes to goods where orders are placed relatively far in advance), which is why manufacturing indicators like the ISM Index are closely watched by analysts and forecasters.

One critique of the ISM Manufacturing Index is that it's noisy, sometimes predicting larger swings than the economy winds up experiencing by exaggerating both positive and negative signals. And since manufacturing is only one part of the U.S. economy (and smaller than it once was), even highly accurate predictions wouldn't necessarily tell the full story about whether a recession is imminent. Still, because it's so forward-looking, it's a signal that many incorporate into a larger analysis.

There are other indicators that measure manufacturing as well, though the more accurate ones are not leading indicators the way the ISM Index is designed to be. The Industrial Production Index, for example, is a monthly measure of the output of several sectors, including manufacturing and manufacturing inputs (such as mining), but that tells you what production was. Meanwhile, survey-based indicators sacrifice accuracy for attempting to include information about what production will be.

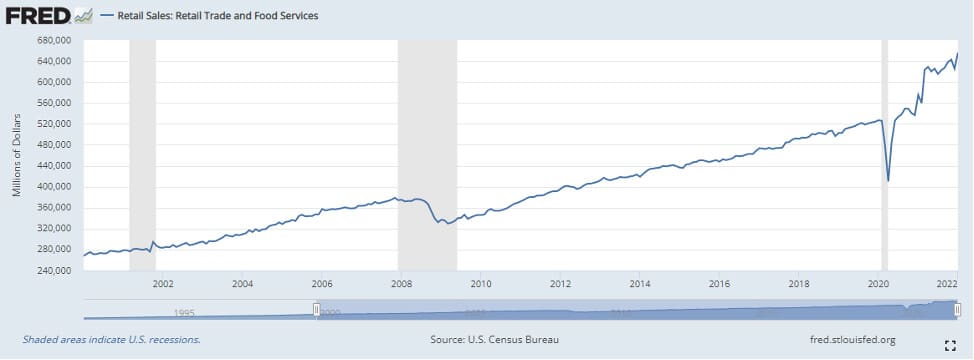

7. Wholesale/Retail

While manufacturing indicators seek to measure changes in economic activity by looking at the "makers" — factory orders and output — retail indicators look at the buyers. They usually measure retail sales in inflation-adjusted dollars, which is useful because the first sign of an economic downturn is sometimes a drop-off in consumer demand. Manufacturing happens based on forecasts and predictions, but consumer behavior in stores is what ultimately determines how much of the manufactured product gets sold. Wholesale sales are another place where changes in demand can be observed, and those sales figures are used similarly to retail sales when identifying trends and making predictions.

The start of the COVID-19 pandemic is a good example of a situation when retail sales provided an earlier indication of problems than manufacturing indicators. Shutdowns and precautions happened abruptly, and consumers immediately reduced their retail spending and shopping, venturing out to buy little more than the essentials. Many consumers suffered a loss of income and feared it would be persistent, so spending shrank even further. Manufacturers responded too, of course, but the most immediate impact up and down the supply chain could be seen in empty retail stores.

You can see the sharp dip in March and April 2020 on this chart of "Retail Trade and Food Services," from January 2000 through January 2022. Shaded areas are recessions.

U.S. Retail Trade and Food Services, 2000-2022

Retail sales are a closely watched recession indicator.

There are many indicators that track sales, including surveys of retailers and breakdowns by product type (e.g., vehicles or food), by channel (e.g., ecommerce vs. brick-and-mortar stores) and geographic region. Many economic indicators are seasonally adjusted — that is, curves are mathematically smoothed to remove highly predictable spikes and dips that happen every year so readers can focus on larger trends and aberrations from the norm. That’s an especially important point for retail sales, which would otherwise have big spikes in December and dips every February.

8. The Stock Market

One of the most commonly referenced indicators of economic health is the stock market, represented by various indexes. The S&P 500, an index of 500 of America's largest companies, is probably the most popular for this purpose. Since markets supposedly incorporate the wisdom of crowds — or at least crowds of investors — stock prices respond to future expectations. That means individual share prices can be considered a leading indicator of company health, and the aggregated indexes are a leading indicator of economic health.

The main issue with the stock market is that it's a sensitive and noisy (if not outright jumpy) measure. It does go down in recessions and often starts falling in advance of recessions, but it's also very volatile in general. Sometimes stock market downturns are just corrections for spikes based on unjustified enthusiasm. Sometimes they're based on fears that never materialize. There can be a herd mentality to stock trading as well. A classic joke highlighting the stock market's predictive power was famously told by Paul Anthony Samuelson, the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Economics, when he observed, "The stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions."

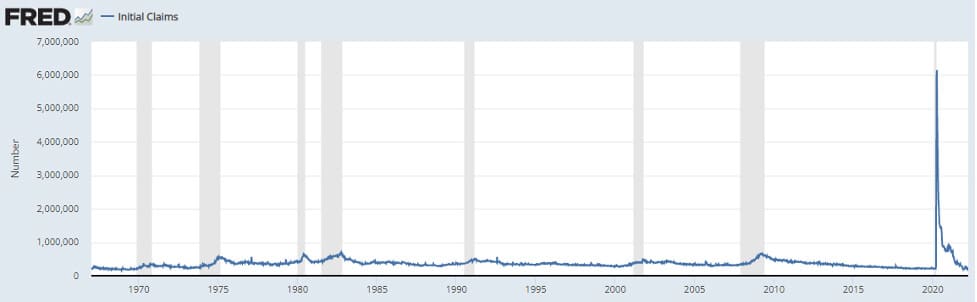

9. Unemployment

Rising unemployment is a likely sign that a country's economy is increasingly struggling, and prolonged above-average unemployment is a sure sign that times are tough. Unemployment is a powerful indicator but not one that's very helpful in predicting recessions because job losses tend to happen mid-recession, not at the outset or in advance.

There are several different ways of looking at unemployment, and it's worth thinking about from those different angles because they may tell you different things. The most common metric is the official unemployment rate. It's straightforward: When it goes up, that's bad, and when it goes down, that's good. But there are nuances it doesn't capture. More expansive measures of unemployment take into account underemployment — how well the labor force is being utilized. Someone working part-time but looking for full-time work or someone in a job that's a poor match for their skills and is looking for a job that makes better use of their talents and training would be considered underemployed. High rates of underemployment don't count toward the official unemployment rate, but they do indicate a struggling labor market.

Initial claims for unemployment insurance is another unemployment indicator, published weekly, that tallies the number of people newly filing for unemployment benefits. This is a more timely metric of how bad the labor market situation was that week. Some turnover in labor markets is natural, and very good economies might see weekly initial claims in the two- or three-hundred thousands. In times of struggle, those numbers can creep higher. Past recessions have seen initial claims jump to almost 700,000 a week. For example, the first week impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic saw 6,149,000 new claims for unemployment insurance. Claims stayed at unprecedentedly high levels through the beginning of 2021, when they began a decline to normal levels.

Initial Claims for Unemployment Benefits, 1965-2021

Initial claims for unemployment insurance spiked in tandem with the start of the last recession in February 2020.

For longer periods of economic downturn, the labor force participation rate becomes something to watch. A person is only counted as unemployed if they're actively looking for a job. Sometimes unemployed people stop looking. If they do, they're considered to have dropped out of the labor force, becoming what economists call "discouraged workers." They may retire early if they're able or, if not, find other ways of getting by while waiting for the job market to recover. In a long recession, a falling labor force participation may indicate that the toll it's taking is high and recovery will be difficult.

10. Housing and Households

There are two economic indicators that describe, broadly, how people are living: housing starts and household formation. Housing starts track the number of new residential construction projects. When the number drops, it signifies a lack of demand and/or investment in housing. That usually signals economic contraction, unless it's in response to a prebuilt oversupply. In the latter case, prognosticators need to look deeper. If the cause of the oversupply was that builders overestimated consumers' ability to buy homes, that's a possible recession signal. But if builders had just ramped up production because labor and materials were unusually inexpensive at the time, that may not be a bad sign.

Household formation is a similar metric, but instead of speaking to the homes themselves, it describes the number of new family units created. A "household" is usually defined as a group of people living together and sharing resources; you could have two households under one roof if, for example, two roommates buy their own food, have their own transportation and keep relatively separate. New households are formed when people leave one household to start another. If household formation drops, it could be a sign that college students and other young adults are living with their parents instead of "leaving the nest" to start independent lives. That can speak to parts of the economy that are already weak, such as the job market, while also serving as an advance warning that demand growth will slow or reverse, as there won't be as many people buying and renting homes and purchasing the items one needs to start a household. Household formation is not one of the most common indicators, but some economic forecasters speak highly of its ability to round out a picture of what's happening in an economy and improve predictions.

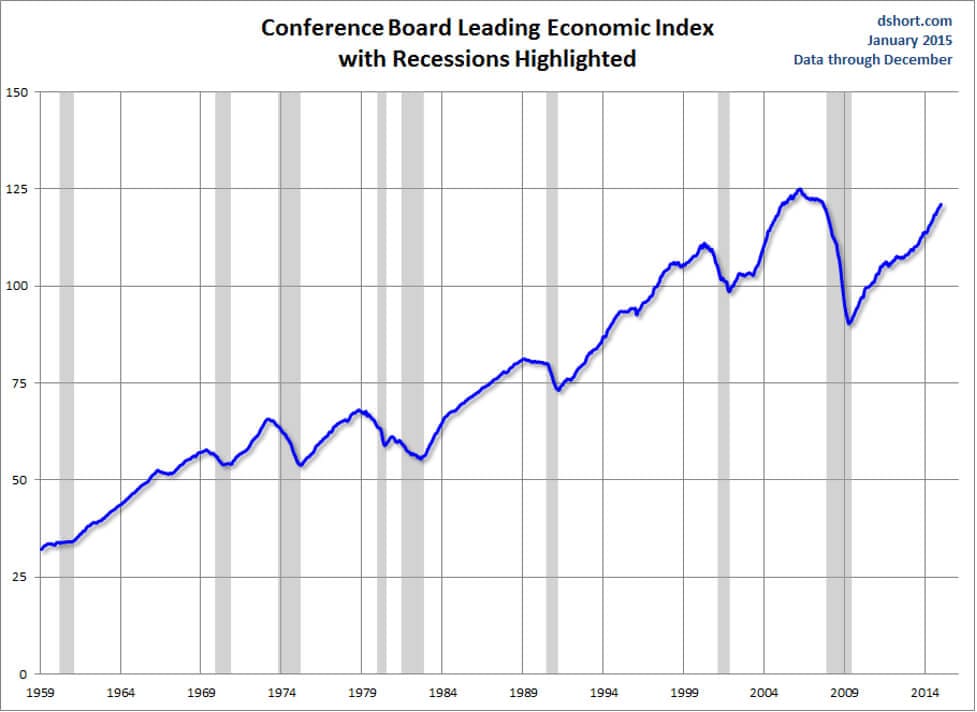

11. Leading Economic Index (LEI)

The Leading Economic Index, or LEI, is a composite index of other economic indicators. It's put out by The Conference Board, a nonprofit industry association that conducts research on behalf of its members, which include a majority of Fortune 500 companies. The LEI includes measures of several factors discussed here already, plus some others, including stock prices, new unemployment claims, several manufacturing indicators and a measure of yield curve slope (they compare the yield of 10-year Treasury bonds to the Fed Funds Rate). As the LEI rises, it means the economy is doing better; a falling LEI signals worsening conditions.

Recession Causes

Though there are countless different possible causes of a recession, they generally fall into one of four different categories: structural shifts in society or the economy, sudden changes in external conditions, psychological factors and financial factors.

Structural shifts.

Sometimes structural shifts in the way societies and economies operate can cause recessions. Workforces can't upgrade their skills and move overnight, and economic responses to events take time. Structural shifts can be caused by governments implementing policy changes (governments rarely try to cause bad economic outcomes, but policy changes can have unintended consequences), but the most persistent structural shifts are often caused by technological developments or external factors, like environmental changes. Sometimes these are good developments, such as the advent of computers. But even in those cases, there are still winners and losers (e.g., once everyone learned how to type, jobs dried up in typist pools). The structural shift involving the rise of microcomputer technology during the 1980s is considered a contributing factor to the 1990-1991 recession.

Sudden changes in external economic conditions.

Abrupt changes, especially disruptions, can trigger recessions. If an important widely used input, such as food or oil, suddenly becomes scarcer and consequently more expensive, that can trigger a recession as consumers and businesses struggle to adapt. Natural disasters are a common cause of recessions, since they can disrupt production and have knock-on effects, from displaced people to loss of infrastructure, that prevent recovery. While natural disasters are usually localized, they can be national or even global. The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the worst disruptions we've seen of this type in the last century, and while the stock market and other sectors have recovered, many people, industries and geographic areas have not.

Because of the unexpected nature of sudden shocks and adverse events that alter economic conditions, these recessions tend to be the most difficult to predict. Everything could be fine until the precipitating event happens, after which recession conditions can occur very rapidly.

Psychological factors.

Sometimes bad economic events happen because people think they're going to happen. Economies and markets are made up of people making choices. If people fear spending will slow down and the economy will decline, they slow their own spending so they can save money to prepare. In that way, the fear alone can create the very thing the people feared. If everyone thinks stocks are going to go down, they sell their stocks, causing stocks to go down. If people are afraid a bank won't be able to cover its deposits, they rush to withdraw money and cause the bank to run out of funds. Such bank runs have brought down entire financial institutions, though this happens less now thanks to deposit insurance and easy interbank lending. In all of these cases, major negative consequences happen as a result of psychological factors that become self-fulfilling prophecies.

Many of the recession indicators discussed in this article tend to amplify how psychology and expectations feed into our bellwethers of recession. If consumers have a dismal outlook, consumer sentiment indexes drop. If investors believe the Fed will need to cut interest rates, their belief could invert the yield curve. The psychology of economic actors can very much impact economic conditions, including causing or worsening a recession.

Financial factors.

These can play a big role in creating recessions, as anyone who lived through the 2008 Great Recession can attest. That recession was caused almost entirely by financial institutions and financial factors, with a few holes in governmental policy enabling but not causing the cascades that caused so many problems. There were causal factors in commercial banks (lending too much to borrowers with a poor ability to pay back the loans), investment banks (using financial engineering to mask the risks associated with certain investments), and rating agencies (supposed watchdogs who gave high-quality ratings to what turned out to be very risky investments).

The variety of financial factors that can cause a recession is large. What's consistent about them is that sometimes the constructs, institutions and economic mechanisms a society sets up to enable economic growth can become the very engines of recession. Good government policy can substantially mitigate the risks of financial factors causing recessions and other adverse economic events, but as our national and international economic systems become increasingly intertwined and complex, oversight becomes harder both in terms of knowing what to do and in terms of getting it done.

Because financial factors are the most likely to appear in economic data, these recessions may be the most likely to appear in indicators before the recessions start. However, it's not always obvious until after the fact which data is signaling most loudly that a contraction or collapse is imminent.

Effects of a Recession

Recessions are periods of economic slowdown and contraction. This often means a loss of wealth and resources to individuals, organizations and entire societies. Recessions put downward pressure on investment portfolios and wages alike, while causing lenders to be more hesitant about making loans. Those who feel a recession most acutely may be the ones who lose a job or a business (usually a single-digit percentage of affected people), but tighter resource constraints can impact a majority of the population during a recession. In the United States, where a job loss or even being cut back to part-time can often mean a loss of health insurance (and therefore loss of access to most healthcare), employment pullbacks are particularly problematic. That's one of several reasons why recessions can cause poor health and even extra deaths; many peer-reviewed academic studies have confirmed that recessions lead to increases in a society's overall mortality rate.

Temporary, even very short-lived recessions can also have longer-term impacts. Students graduating in a recession often wind up having to accept lower-paying job offers or take longer to find a job, and that's been shown to have long-lasting effects that meaningfully depress their lifetime earnings, on average. Older workers approaching retirement may find their plans too optimistic if their savings are in investments that lose substantial value due to the recession. And as companies make do with fewer resources and slower sales, often the most important activities are cut, such as investments in transformational innovation. But cutting R&D spending, especially for the big, long-shot projects with high potential, slows the development of breakthroughs.

Stay Ahead of Your Financial Indicators With NetSuite Financial Management

Recession-proofing a business requires planning and action before and during an economic downturn. Business leaders need useful and accurate financial data, along with robust external analysis tools in order to develop those plans and execute their strategies. NetSuite provides the real-time visibility into your business's financial and operating data to help business leaders truly understand current results, as well as to develop what-if scenarios and forecasts. NetSuite also provides the controls that can help an organization manage costs more effectively, along with automating processes that can make the business more efficient, and workers more productive. Real-time access and reporting dashboards, including KPIs, allow business leaders to closely monitor results and act quickly as these indicators appear.

Conclusion

There's no foolproof way to predict if and when a recession will occur, especially ones caused by abrupt shifts or shocks, like a natural disaster. But we've never had better information that speaks to so many different aspects of the economy. Diligent observers will be able to pick up signals that indicate not only if there are causes for concern, but what those causes might be and how a recession might form.

Recession Indicator FAQs

Can we predict a recession?

Despite an abundance of indicators, we can't predict recessions with complete accuracy. Economists can make statements about the probability of a recession and how that probability goes up or down based on observed economic data and historical precedent, but they will likely never be able to predict recessions perfectly. Even as the understanding of economic indicators improves and the treasure trove of historical data grows, there will always be the possibility for sudden events, like natural disasters and breakthrough innovations, that can cause a recession — or avert one.

Why is a recession bad?

Recessions are periods in which the economy slows and shrinks. This can mean a reduction in wealth as asset prices fall, income as tough labor markets put downward pressure on wages and hours, and access to credit as lenders become more hesitant and risk averse. From a personal standpoint, it can even mean losing a job and access to healthcare. From a societal standpoint, recessions cause a loss of productivity, innovation, progress and even the health of citizens. While recessions are far from the most threatening dangers humanity faces, recessions are adverse events that should be avoided, shortened and mitigated to the extent we're able.

What are the leading indicators of a recession?

A "leading indicator" is an indicator that provides a signal in advance of an event. Leading indicators for recessions are thought to include the shape of the Treasury yield curve (an inverted curve — when short term bonds have higher yields than long term bonds — could be a signal), measures of confidence among consumers and businesses, and even the stock market. Other recession indicators, such as GDP — a main indicator used to determine whether there is a recession — provide concurrent or lagging information, speaking to whether there is or was a recession.

How do you identify a recession?

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), which declares what is and isn't a recession for the U.S., defines a recession as "a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months." A historical rule of thumb is that a recession can be identified by a decline in GDP for two consecutive quarters, although some recessions are shorter. To identify recessions, NBER analyzes many different economic factors, including personal income, employment, personal consumption, wholesale-retail sales and industrial production.

What are 4 indicators that are looked at to determine a recession?

Among the indicators looked at by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) to identify recessions are gross domestic product (GDP), people's real personal income, unemployment levels and measures of commercial activity, such as retail sales and industrial production.

What are 5 causes of a recession?

There are many ways to cognitively classify the causes of a recession. The article above breaks it down into four, but you could also partition recession instigators into these five categories:

- Structural shifts in the economy or society, such as new technology shocks.

- Sudden shifts in external factors, such as a spike in oil prices.

- Financial factors, such as a sharp constriction of credit (as we saw in 2007 and 2008).

- Psychological factors, in which negative expectations become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

- Policy triggers, such as a sharp reduction in government spending or raising interest rates during a time of economic struggles.